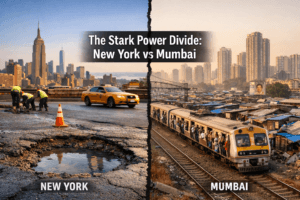

Why Your City’s Mayor Can’t Fix That Pothole: The Stark Power Divide Between New York and Mumbai

The recent global attention on New York City’s mayoral election starkly highlights the profound governance deficit faced by Indian megacities like Mumbai, where mayoral power is largely ceremonial rather than executive.

While New York’s mayor operates as a powerful chief executive under a city charter that grants sweeping authority over police, transport, housing, and planning—treating the city as a quasi-autonomous entity—Mumbai’s mayor is merely an indirectly elected presiding officer with a limited 2.5-year term, devoid of control over critical functions like policing, mass transit, or housing, which remain under state government control.

This structural disempowerment, rooted in outdated state statutes and a constitutional framework that leaves cities at the mercy of state governments, results in fragmented accountability, chronic underfunding, and dysfunctional urban management, ultimately stifling the potential of India’s rapidly urbanizing economic engines and relegating municipal elections to exercises in party politics rather than meaningful contests over urban governance and citizen-centric solutions.

Why Your City’s Mayor Can’t Fix That Pothole: The Stark Power Divide Between New York and Mumbai

The recent mayoral election in New York City captured global headlines, a spectacle of political debate, policy platforms, and the transfer of significant executive power. Halfway across the world, as Mumbai prepares for its own municipal elections, the contrast couldn’t be more profound. Here, the election is often a subdued affair, dominated by party calculus rather than a contest for a powerful urban chief executive. This divergence isn’t merely cultural or political; it is a fundamental reflection of how two of the world’s great democracies have chosen to structure—or disempower—their cities.

At the heart of this lies a simple, powerful distinction: New York’s mayor is the CEO of a city-state, while Mumbai’s mayor is a ceremonial presiding officer. One wields the authority to shape the destiny of a global metropolis; the other presides over meetings. Understanding this chasm is key to diagnosing why Indian cities often feel ungovernable, despite their economic might.

The Constitutional Crucible: How Cities Are Born

The power of a city is first determined by the legal womb from which it is born. New York City, though within New York State, operates with remarkable autonomy under its NYC City Charter. This charter, authorized by the state constitution, is unequivocal: “The mayor shall exercise all the powers vested in the city.” He is the chief executive officer, commanding a four-year term, with sweeping authority to appoint and dismiss commissioners, control the budget, and set the agenda for a vast urban machinery. The governor retains a theoretical removal power, yet it has never been used, underscoring a tradition of respected city autonomy.

Mumbai’s Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), one of India’s wealthiest municipal bodies, draws its life from a different source: the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation Act of 1888. This pre-Independence legislation sets the tone. The mayor is not directly elected by the city’s 14 million residents. Instead, Section 37 dictates that the 227 elected councillors elect one from among themselves to be mayor for a mere 2.5-year term. The mayor’s primary statutory duty? To convene and preside over monthly corporation meetings. The role is, by design, ceremonial, with real executive power vested in the Municipal Commissioner—a career bureaucrat appointed by the state government of Maharashtra.

This structural difference is not an accident of history but a conscious choice of governance. The United States, through home rule provisions, often treats its major cities as empowered entities, mini-states capable of self-governance. India’s Constitution, through the 74th Amendment, aimed to empower Urban Local Bodies (ULBs). Yet, it left the “devolution of powers and functions” to the discretion of state governments, which have been notoriously reluctant to cede control.

A Tale of Two Agendas: What Cities Actually Control

The scope of a mayor’s ambition is defined by the functions they control. Examine the portfolio of the NYC Mayor, and you see the blueprint of a self-contained republic:

- Public Safety: Commands the NYPD, one of the largest police forces in the US.

- Transportation: Oversees the city’s streets, traffic systems, and a massive public transit network.

- Planning & Development: Directs the Department of City Planning and Housing Preservation and Development.

- Critical Services: Manages departments for fire, sanitation, environmental protection, health, and education.

- Social & Equity Framework: Operates dedicated offices for immigrant affairs, homelessness, veterans, gender equity, and climate sustainability.

The philosophy is clear: issues that predominantly affect city residents should be managed by a city government accountable to those residents.

Mumbai’s BMC, while large, operates within a tightly corseted mandate. Its obligatory functions are largely limited to “hard” municipal services: water supply, sewage, solid waste management, street lighting, and maintenance of roads and public parks. The most critical levers of urban life—the ones that define quality of life, economic mobility, and safety—are held by the state government:

- Policing: Controlled by the Maharashtra Home Department.

- Mass Transit (Suburban Rail, Metro): Managed by state-controlled or central agencies.

- Housing & Slum Rehabilitation: Primarily a state subject.

- Major Infrastructure: Highways, major bridges, and regional planning fall under state bodies.

The result is a fractured governance model. A Mumbaikar grappling with a water-logged street (BMC), a harassing commute (state rail agency), and housing insecurity (state department) must navigate a labyrinth of unaccountable entities, none of which possesses a holistic mandate for the city. The mayor, who should be the natural locus of accountability, is institutionally powerless to coordinate solutions.

The Price of Disempowerment: Dysfunction and Missed Potential

The “ceremonial mayor” model has profound consequences. It fragments accountability, allowing state and city agencies to pass the buck. It stifles innovation, as bold, city-specific solutions require state approval. It perpetuates party politics over governance, as municipal elections become a proxy battleground for state parties, not a debate on urban vision.

Most critically, it leaves Indian cities chronically underfunded. They lack the fiscal autonomy to raise significant resources or issue bonds against future revenues like their global counterparts. They remain supplicants to state finance commissions, their ambitions held hostage to larger political calculations.

India is urbanizing at a breathtaking pace. By 2030, it will have over 70 cities with populations exceeding one million. These cities are the engines of the national economy. To expect 21st-century economic engines to run on 19th-century administrative frameworks is a recipe for crisis. The climate emergency, public health challenges, and the demand for equitable services require integrated, agile, and powerful city governments.

The Path Forward: From Ritual to Real Authority

Reforming this system is not about copying New York, but about learning its core principle: subsidiarity. The authority to govern should reside at the level closest to the people affected. A meaningful overhaul for India’s cities must include:

- Direct Election & Empowered Mayors: Move to directly elected mayors with five-year terms, vested with clear executive authority over all city agencies, including those currently with the state.

- Functional Clarity: Legally devolve crucial functions like city police, housing, and transport to ULBs, with appropriate funding mechanisms.

- Financial Autonomy: Empower cities with greater taxation powers, bond-issuing authority, and a guaranteed share of state GST proceeds to build fiscal resilience.

- Professional Council: Transition the city council to a strategic legislative and oversight body, akin to NYC’s, holding the mayor’s administration accountable.

Mumbai’s upcoming municipal election will see the usual fanfare, promises, and political maneuvering. Yet, unless the conversation shifts from who wins the ceremonial chain to how we can restructure power itself, the outcome will change little for the citizen navigating potholed roads and overcrowded trains. India’s urban future depends on building cities that are not just large in population, but powerful in purpose. It’s time to move beyond the era of the square-circle mayor and build leaders who can truly run their cities.

You must be logged in to post a comment.