When Conscience Clashes with the Dock: The Acquittal That Questions More Than a Crime

In a striking legal and moral verdict, six Palestine Action activists were acquitted of aggravated burglary and other serious charges related to their 2024 break-in at an Israeli defence firm’s UK factory, despite openly admitting to damaging property, after a jury deliberated for over 36 hours and ultimately refused to convict them, highlighting a profound clash between strict legal definitions and perceived moral imperative, as the defence successfully framed their actions as a desperate attempt to disrupt equipment they believed was facilitating genocide, drawing comparisons to historic civil disobedience movements and implicitly invoking the principle of jury nullification, which delivered a significant symbolic setback to the UK government’s recent decision to proscribe the group as a terrorist organisation.

When Conscience Clashes with the Dock: The Acquittal That Questions More Than a Crime

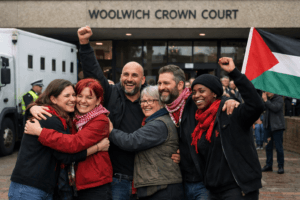

The scene at Woolwich Crown Court was one of embrace and muted triumph. Six activists, who had openly admitted to forcing entry into a defence contractor’s factory and destroying property, were not convicted of the most serious charges against them. The jury’s decision to acquit the Palestine Action members of aggravated burglary—a charge carrying potential life imprisonment—and their failure to reach verdicts on other counts, is far more than a legal footnote. It is a prism through which we can examine the fraying edges of legal dissent, the powerful role of jury nullification, and the intensely personal calculus of morality in an age of global conflict.

The Facts of the Case and the Fracture in Narrative

On the surface, the event at Elbit Systems’ Filton factory in August 2024 was dramatic and confrontational. A prison van was driven into the site; activists armed with sledgehammers entered, damaging computers and drones. The prosecution painted a picture of threatening, planned violence, alleging weapons were swung at security guards. The defence did not dispute the physical acts of entry and damage. Instead, they presented a narrative of desperate, unplanned action by individuals “completely out of their depth,” reacting to what they saw as a greater moral emergency.

This is where the trial ceased to be a simple matter of establishing what happened, and became a battle over why it happened, and whether that why mattered. The prosecution, led by Deanna Heer KC, and the judge, Mr Justice Johnson, repeatedly instructed the jury to disregard their views on the Middle East conflict. The law, they implied, was a sealed chamber. Yet, the very asking of the question by a juror—whether preventing a genocide could be a “lawful excuse”—blew a hole in that chamber’s wall. It revealed the human impulse to contextualise action within a framework of justice that can feel more urgent than statute.

The “Conscience Defense” and the Ghost of the Suffragettes

The defence’s comparison of the activists to the suffragettes was not merely rhetorical flair; it was a strategic invocation of a powerful historical precedent. The suffragettes, now widely venerated, were in their time criminalised, force-fed, and condemned as violent radicals for their property damage and civil disobedience. Their actions were deemed illegal, but history has judged their cause as just. By drawing this parallel, defence barrister Rajiv Menon KC was inviting the jury to consider themselves not just as assessors of fact, but as participants in a moral judgment that stretches across time. He was asking: “Will you convict those who break laws to protest what they see as a greater crime against humanity?”

This taps into the ancient, fragile principle of jury equity or nullification—the absolute right of a jury to acquit a defendant, regardless of the evidence, if they believe a conviction would be unjust. The judge’s direction that a belief in preventing genocide was not a lawful excuse in law was technically correct. But the jury’s ultimate acquittals speak to a different truth: that in the quiet sanctum of the jury room, the conscience of twelve citizens can, and sometimes does, outweigh the black letter of the law.

The Unseen Evidence and the Shadow of the State

The defence’s pointing to “missing CCTV footage” and allegations of “excessive force” by security weaves another critical thread: the perception of imbalance. For activists and their supporters, the state’s vast resources—in policing, prosecution, and the recent proscription of Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation—stand in stark contrast to the hammer-wielding individuals in the dock. Clare Rogers’ statement after the verdict crystallised this: “The government is determined to do business with Israel and protect its weapons industry at any cost… Imagine if the government had put the same amount of money, resources and political will into preventing a genocide.”

This framing positions the activists not as aggressors, but as David poking a Goliath of corporate-military-state interest. Whether one agrees with this characterisation or not, its potency in the courtroom and the public gallery is undeniable. It transforms a burglary charge into a story about power, prioritisation, and who the state chooses to protect.

The Aftermath: A Blow to Strategy, a Boost to Symbolism

The government’s proscription of Palestine Action in 2025 sought to categorise the group as beyond the pale of legitimate protest. This acquittal, described by Defend Our Juries as a “huge blow to government ministers,” fundamentally undermines that narrative. If a jury, presented with the facts, refuses to convict core members of the gravest charges, it becomes harder to sustain the public portrayal of the group as primarily violent terrorists. As Amnesty International noted, it highlights the “disproportionate” nature of the ban.

For the movement, the verdict is a potent symbolic victory but a fraught practical one. It validates a strategy of high-risk, direct action by demonstrating that public sympathy—as reflected in a jury of peers—can intervene. However, it does not change the law. The activists still face the possibility of retrial on the undecided criminal damage charges. The proscription remains. The personal costs—the strain of a long trial, the threat of imprisonment—are immense.

The Enduring Question: Where Does Legitimate Protest End?

This case does not provide easy answers. It forces uncomfortable questions that are essential for a healthy democracy:

- Where is the line between criminal damage and morally motivated sabotage? Is it the cost of the property, the intent behind the act, or its potential to save lives elsewhere?

- Can a legal system designed for order adequately process claims of conscience rooted in global injustice? The instruction to “disregard the Middle East” is almost impossible to obey when the defendants’ entire motive is defined by it.

- What is the role of a juror? Are they merely a fact-checker for the state, or the final conscience of the community?

The Woolwich verdict is a testament to the enduring, messy humanity of the jury system. It reveals that in moments of profound political and ethical conflict, the law is not a robotically applied code, but a conversation—sometimes a shouting match—between power, principle, and the people asked to sit in judgment. The six activists walked free not because they didn’t do what they were accused of, but because enough members of the jury, after 36 hours of deliberation, could not bring themselves to say that in this specific, charged context, it constituted the grave crimes the state alleged. In that nuanced, hard-won space of doubt, a small but resonant victory was claimed for the idea that sometimes, the public conscience can demand a different kind of accounting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.