Trump’s Gaza Plan: An Ambitious Blueprint Collides with Violent Reality

The Trump administration’s Gaza plan, unveiled at Davos as part of a “Board of Peace” initiative, outlines an ambitious vision for a unified, Palestinian-run Gaza managed by a technocratic committee, marking a rebuff to Israeli factions seeking to displace the population. The plan’s immediate goals include reopening the Rafah crossing and restoring basic infrastructure, but its long-term success hinges on overcoming monumental challenges: compelling Hamas to disarm, navigating fierce opposition within Israel’s government, securing massive reconstruction funding, and establishing a new Palestinian governance structure that currently lacks broad legitimacy or a clear pathway to sovereignty, all while addressing the vast physical destruction and humanitarian crisis on the ground.

Trump’s Gaza Plan: An Ambitious Blueprint Collides with Violent Reality

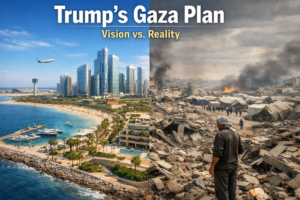

The latest American plan for Gaza offers gleaming skyscrapers and international airports, yet faces a landscape of 60 million tons of rubble and a population living in tents.

In a high-profile ceremony at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Donald Trump and his son-in-law Jared Kushner unveiled a vision for Gaza’s future that felt more like a real estate pitch than a geopolitical roadmap. The plan, part of Trump’s “Board of Peace” initiative, promises to transform the war-ravaged territory into a prosperous hub with coastal tourism zones featuring 180 skyscrapers, new cities, and state-of-the-art infrastructure.

Behind the slick presentations and dreamscape imagery of gleaming towers lies a sobering reality. More than two years of conflict have left over 80% of Gaza’s buildings damaged or destroyed, creating 60 million tons of rubble—enough to fill nearly 3,000 container ships. The United Nations estimates clearing this debris will take over seven years, even before reconstruction can begin.

This plan represents the official launch of Phase Two of the “Comprehensive Plan to End the Gaza Conflict,” a 20-point peace agreement that took effect in October 2025. While offering a rebuff to Israeli extremists seeking to displace Gaza’s population, its success hinges on overcoming monumental obstacles, from disarming Hamas to navigating bitter political divisions.

The Vision Versus the Reality

The presentation by Jared Kushner at Davos painted a picture of a future Gaza that seemed transplanted from the Persian Gulf. The “Master Plan” shown to world leaders included:

- A “coastal tourism” zone running along the Mediterranean, designed for up to 180 skyscrapers, many likely earmarked as hotels

- A new port and airport near the Egyptian border

- Two new urban developments dubbed “New Rafah” and “New Gaza,” with over 100,000 permanent housing units, 200 schools, and 75 medical facilities promised for the former

- Designated zones for “advanced manufacturing,” “data centers,” and “industrial complexes”

Table: Contrasting Visions for Gaza’s Future

| Kushner’s “Master Plan” Vision | Current Reality in Gaza |

| 180 skyscrapers along the coast | 60+ million tons of rubble |

| New port and airport infrastructure | Previous airport destroyed 20+ years ago |

| “New Rafah” with 100,000+ homes | Rafah largely leveled by Israeli strikes |

| Phased development over 2-3 years | UN estimates 7+ years just for rubble clearance |

| “Bustling commercial and tourist center” | 1.6 million facing acute food insecurity |

Kushner expressed optimism about the timeline, stating, “In the Middle East, they build cities like this … in three years”. However, this outlook starkly contrasts with assessments from humanitarian organizations and the lived experience of Gazans.

For the territory’s displaced population, the presentation raised immediate practical concerns. Ahmed Awadallah, sheltering in a displacement camp in Khan Younis, voiced a common worry: “I was planning to pitch a tent where my old house was, and gradually rebuild my life again”. The vision of high-rises left him concerned his family might, at best, end up in a small apartment in one of them.

Key Players and Political Architecture

The plan’s implementation rests on a complex new governance structure that attempts to bypass existing political divisions while establishing international oversight.

The Diplomatic Operator: Nickolay Mladenov

At the operational heart of the plan is Nickolay Mladenov, a 53-year-old Bulgarian diplomat appointed as the High Representative for Gaza. Mladenov brings a rare profile to this fraught assignment—a diplomat trusted by both Israeli and Palestinian officials during his previous role as UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process.

A senior Israeli official described him as someone who “speaks in a positive and constructive manner, avoids getting stuck on the negatives, and works in an orderly and transparent way with everyone”. However, his appointment is not without controversy. Since 2021, Mladenov has served as director-general of the Anwar Gargash Diplomatic Academy in Abu Dhabi, where he became a vocal proponent of the Abraham Accords—the normalization agreements between Israel and several Arab states.

For many Palestinians, these accords represent the diplomatic architecture that sidelined their aspirations for statehood. This places Mladenov in the challenging position of implementing a US-designed plan while navigating Palestinian skepticism about his alignment.

The Technocratic Leader: Dr. Ali Sha’ath

On the ground in Gaza, administration would fall to the National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG), led by Dr. Ali Sha’ath. Described by the White House as “a widely respected technocratic leader,” Sha’ath is a former deputy minister in the Palestinian Authority with experience in public administration and economic development.

In his first official statement, Sha’ath emphasized that the NCAG aims to “establish security, restore essential services including electricity, water, healthcare and education, and promote governance rooted in peace, democracy, and justice”. He has announced the imminent reopening of the Rafah crossing between Gaza and Egypt—a move symbolizing that “Gaza is no longer closed to the future and to the world”.

The Board of Peace: An International Umbrella

Overseeing this entire structure is Trump’s “Board of Peace,” chaired by the President himself. The board’s Executive Committee includes prominent figures such as:

- U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio

- Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor Jared Kushner

- Former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair

- World Bank President Ajay Banga

The international composition of the broader board reveals both support and significant gaps. While countries including the United Arab Emirates, Hungary, Pakistan, and Qatar participated in the signing ceremony at Davos, notable absences included Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy. European nations expressed reservations, with Belgium’s foreign minister stating, “We wish for a common and coordinated European response. As many European countries, we have reservations to the proposal”.

Four Monumental Challenges

Despite the ambitious vision and high-profile backing, the plan confronts obstacles that have derailed previous peace initiatives.

- The Demilitarization Dilemma

The entire reconstruction premise hinges on a condition Kushner explicitly stated: “Hamas signed a deal to demilitarize, that is what we are going to enforce”. The plan calls for “heavy weapons, tunnels, military infrastructure, munitions and production facilities” to be destroyed.

Hamas has historically refused to disarm without the creation of an independent Palestinian state. More recently, Basem Naim, a senior Hamas official, has spoken of “freezing or storing” its arms in the context of the current ceasefire rather than surrendering them. The militant group has agreed in principle to hand over administration to a Palestinian body of technocrats but has been vague about relinquishing military control.

- Israeli Political Resistance

The plan faces significant opposition within Israel’s governing coalition. Far-right elements remain “bent on emptying and annexing” Gaza territory. Even the reopening of the Rafah crossing—scheduled for the coming week—faces internal opposition, with some coalition members insisting it remain closed until the remains of the last unaccounted-for Israeli hostage are returned.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has adamantly opposed any proposal for postwar Gaza that involves the Palestinian Authority. The plan attempts to navigate this by positioning the NCAG as a temporary technocratic body that would eventually hand over control to a reformed Palestinian Authority, but this compromise may satisfy neither side.

- The Palestinian Authority’s Precarious Position

The Palestinian Authority (PA) views the new technocratic committee with understandable suspicion. Quietly, PA officials have expressed concerns that the NCAG “represents a threat to its centrality in Palestinian politics”. Former PA Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh articulated this tension: “The Palestinian Authority as an interim authority has been there for the last 32 years, and now there is the (new) authority in Gaza … which is also an interim arrangement”.

The PA’s popularity has waned in both Gaza and the West Bank due to perceptions of corruption and collaboration with Israel. Any plan that further undermines its standing risks deepening Palestinian political fragmentation.

- Funding and Implementation Realities

The scale of destruction makes reconstruction a colossal financial undertaking. The latest joint estimate from the UN, European Union, and World Bank places the cost at approximately $70 billion. Kushner suggested that governments would make initial contributions, with announcements expected at a conference in Washington in the coming weeks. He also appealed to private sector investment, promising “amazing investment opportunities”.

However, without security guarantees, private investment remains unlikely. As Kushner himself acknowledged, “without security nobody is going to make investments”. The vicious circle is apparent: demilitarization requires stability, investment requires demilitarization, and stability requires investment in basic infrastructure and livelihoods.

The Path Forward: First Practical Steps

Amid these formidable challenges, the plan does outline some immediate, practical measures:

- Reopening the Rafah Crossing: Scheduled for the coming week, this would represent the first sustained opening since Israeli forces seized control in May 2024.

- Restoration of Basic Services: The NCAG’s initial focus will be on electricity, water, healthcare, and education systems.

- Rubble Clearance in Rafah: Kushner claimed work has already begun to remove rubble in the Rafah area as a precursor to reconstruction.

- Deployment of Palestinian Police: A key component involves allowing the NCAG to enter Gaza with a Palestinian police force trained in Jordan and Egypt over recent months.

The plan notably downplays the previously proposed International Stabilization Force (ISF), which faced recruitment challenges as potential contributors were reluctant to confront Hamas over weaponry. Instead, security responsibilities would fall primarily to the new Palestinian police forces under NCAG authority.

Historical Echoes and Unanswered Questions

This is not Kushner’s first ambitious vision for Gaza. In 2019, he hosted a “From Peace to Prosperity” summit in Bahrain that similarly imagined “a bustling commercial and tourist center in Gaza and the West Bank”. Those plans never materialized due to a “complete lack of political will”.

Several critical questions remain unanswered in the current proposal:

- Where will Gaza’s displaced population live during the reconstruction?

- How will demining of unexploded ordnance be handled when Israel reportedly restricts entry of heavy machinery?

- What happens to competing armed groups in Gaza, which the presentation suggested would either be dismantled or “integrated into NCAG”?

- How will property rights be addressed for generations of Palestinians whose homes have been destroyed?

The plan’s ultimate test may be whether it can transition from a vision presented in Davos to a reality accepted in Gaza’s displacement camps. As Kushner declared with characteristic confidence, “We have a masterplan. … There is no Plan B”. For Gaza’s residents, who have endured multiple cycles of destruction and failed promises, the burden of proof remains with those presenting the latest blueprint for their future.

The coming weeks will prove critical, with the Rafah crossing reopening and the NCAG attempting to establish its presence on the ground. These first practical steps will reveal whether this plan represents a genuine turning point or merely another chapter in Gaza’s tragic history of unrealized aspirations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.