The Stateless Teenager: How India’s Citizenship Laws Failed a Girl Born on Its Soil

A 17-year-old girl born and raised in Andhra Pradesh faced statelessness because her Indian-born parents had acquired U.S. citizenship before her birth. Despite her lifelong residence in India, citizenship laws denied her nationality as her parents weren’t citizens at her birth. In May 2024, a Delhi High Court judge granted her citizenship, ruling she wasn’t an “illegal immigrant” (as she never migrated) and qualified as a “person of Indian origin” through her mother’s Indian birth.

The government appealed, fearing this would “open floodgates” for similar claims. In July 2025, a higher court overturned the ruling, citing a Supreme Court interpretation that “Indian origin” requires ancestral ties to *pre-1947 India*—excluding those like her mother born after independence. While the girl retained her citizenship, the reversal closed a potential path for others in her situation. This exposes a legal gap leaving children born in India to foreign parents stateless, prioritizing bureaucratic rigidity over their fundamental rights.

The Stateless Teenager: How India’s Citizenship Laws Failed a Girl Born on Its Soil

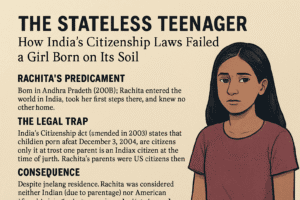

The case of Rachita Xavier exposes a startling gap in India’s citizenship framework—a gap where children born and raised entirely within the country can be rendered effectively stateless due to legal technicalities, despite the Constitution’s promise to prevent statelessness. Here’s the human and legal story behind the headlines:

The Girl Without a Country: Rachita’s Predicament

- Born in Andhra Pradesh (2006): Rachita entered the world in India, took her first steps there, and knew no other home.

- Parents’ Status: Both parents were born Indian citizens but had acquired US citizenship before Rachita’s birth. They resided legally in India as Overseas Citizens of India (OCI) cardholders.

- The Legal Trap: India’s Citizenship Act (amended in 2003) states that children born after December 3, 2004, are citizens only if at least one parent is an Indian citizen at the time of birth. Rachita’s parents were US citizens then.

- Consequence: Despite lifelong residence, Rachita was considered neither Indian (due to parentage) nor American (US citizenship isn’t automatic by birth location). Her 2019 passport application was rejected, leaving her effectively stateless.

A Ray of Hope: The Progressive First Ruling (May 2024) Facing statelessness, Rachita approached the Delhi High Court. Justice Prathiba M. Singh delivered a landmark judgment:

- Not an “Illegal Migrant”: Singh reasoned Rachita couldn’t be classified as an “illegal migrant” (someone entering without documents) because she was born in India. She never “migrated.”

- “Person of Indian Origin” (PIO): Singh interpreted Section 5(1)(a) expansively. Since Rachita’s mother was born in India (Andhra Pradesh, 1958), Rachita qualified as a PIO eligible for citizenship by registration.

- Residency & Human Rights: Having lived in India for 7+ years (easily met), Singh emphasized that denying citizenship violated her right against statelessness under international conventions (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Convention on the Rights of the Child) that India acknowledges.

- The Potential Pathway: This ruling suggested children born in India to foreign parents (where at least one parent was born in post-1947 India) could potentially gain citizenship via registration after 7 years’ residency.

The Government’s Appeal & the “Floodgates” Argument While complying with the order to grant Rachita citizenship (July 2024), the Union Home Ministry vehemently appealed the reasoning:

- Core Fear: They argued the broad interpretation would “open floodgates” for other “illegal migrants” to claim citizenship, “diluting the spirit” of the Citizenship Act.

- Contested Definitions: They insisted Rachita was effectively an “illegal migrant” due to lacking valid travel documents from birth, and challenged the definition of “Person of Indian Origin.”

The Door Slams Shut: The Division Bench Reversal (July 2025) A two-judge bench (CJ Upadhyaya & Justice Gedela) overturned the core reasoning of the first ruling:

- Redefining “Person of Indian Origin”: Crucially, a Supreme Court ruling in October 2024 clarified that “undivided India” (key to the PIO definition) only refers to pre-partition India (pre-August 15, 1947), as defined in the 1935 Government of India Act.

- The Fatal Blow: Since Rachita’s mother was born in 1958 (post-independence), Rachita did not qualify as a PIO under the Act. The first court’s interpretation was deemed “erroneous” and a “misreading.”

- Limiting the “Illegal Migrant” Finding: The bench stated the first judge’s finding that Rachita wasn’t an illegal migrant was specific to her unique facts (born to OCI parents legally residing) and shouldn’t be seen as a general rule for others.

The Lingering Injustice: Roots in India, But No Rights

- Rachita’s Status: She retains her citizenship (granted based on the initial order the government complied with), but the legal basis for it is now undermined.

- The Bigger Picture: The reversal slams shut the potential pathway identified in May 2024. Countless other children born in India to foreign parents (even if one parent was born in India post-1947) now find themselves in a legal limbo:

- They are not citizens by birth (due to parentage rules).

- They likely cannot claim citizenship by registration (failing the strict “PIO” definition requiring pre-1947 roots).

- Statelessness Risk: These children, deeply rooted in Indian soil and society, face the very real risk of statelessness – a condition India’s Constitution explicitly seeks to avoid but its current citizenship laws inadvertently create for this specific group.

The Core Conflict: Security vs. Humanity This case starkly highlights the tension in Indian citizenship policy:

- Government’s Stance: Prioritizes strict control and preventing perceived “floodgates,” fearing misuse and emphasizing statutory technicalities over individual circumstances.

- Human Cost: Results in situations where children who have never known another country, embodying Indian culture and life, are denied formal belonging due to legal gaps and parental choices made before their birth.

The Rachita Xavier case underscores an urgent need for legislative clarity or compassionate administrative policies to address the plight of children born and raised in India who currently fall through the cracks of its citizenship laws, lest India create generations of stateless individuals within its own borders.

You must be logged in to post a comment.