The Silent Partner: How Russian Tech Could Catapult North Korea’s Submarine Threat to a New Level

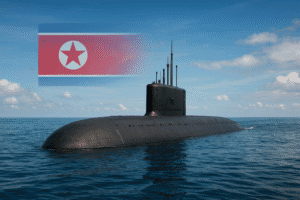

Based on reports that Russia may be supplying nuclear propulsion technology from decommissioned submarines to North Korea, this transfer represents a pivotal strategic shift that would fundamentally enhance the threat posed by Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal. By enabling the construction of a nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine, this technology would grant North Korea a survivable, second-strike capability, allowing its submarines to operate silently for extended periods in the vast Pacific Ocean.

This would make its nuclear forces significantly harder to detect and counter, holding the U.S. mainland at risk from unpredictable vectors and potentially triggering a new regional arms race as allies like South Korea and Japan seek to counter this advanced, persistent underwater threat.

The Silent Partner: How Russian Tech Could Catapult North Korea’s Submarine Threat to a New Level

The image is seared into the mind of any nuclear strategist: a gargantuan, multi-axle transporter rumbling through Pyongyang, carrying North Korea’s latest Hwasong-20 intercontinental ballistic missile. It’s a powerful, terrestrial symbol of a threat that is impossible to ignore. Yet, while the world’s eyes were fixed on this land-based behemoth, a more insidious and strategically transformative development was continuing beneath the surface—literally. North Korea’s pursuit of a credible, sea-based nuclear deterrent is entering its most critical phase, and mounting evidence suggests it has a powerful silent partner: Russia.

This isn’t just about another missile test; it’s about the vessel that will carry them. The potential transfer of Russian nuclear submarine propulsion technology to North Korea represents a tectonic shift in the strategic landscape of the Indo-Pacific. It’s a move that would not only supercharge Kim Jong Un’s ambitions but would fundamentally alter the calculus of nuclear deterrence for the United States, South Korea, and Japan.

The Missing Piece: From Coastal Defender to Global Threat

For decades, North Korea’s submarine ambitions have been hamstrung by a simple problem of physics. Their largest submarines, based on 1950s-era Soviet designs, are simply too small. With a hull diameter of barely 17 feet, these vessels are incapable of carrying the newer, longer submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) like the Pukguksong-3 and -4 in any meaningful numbers. They are, at best, coastal test beds or technological stepping stones.

The new submarine currently under construction, glimpsed in propaganda imagery from a Sinpho shipyard, is a different beast entirely. Its enlarged hull is a clear declaration of intent. But a larger diesel-electric submarine, while an improvement, remains a severely limited strategic asset. Such boats must surface or snorkel frequently to run their diesel engines and recharge batteries, creating a detectable “indiscretion rate.” This makes them vulnerable to modern anti-submarine warfare (ASW) networks, confining them primarily to the defensive waters of the Sea of Japan (East Sea), where they can be monitored and potentially tracked in a crisis.

This is where the Russian technological infusion changes everything. The reported supply of decommissioned nuclear propulsion systems—complete with reactors, steam turbines, and cooling systems—is the key that could unlock the ocean for North Korea.

Beyond the Reactor: A Deeper Strategic Exchange

While the nuclear reactor itself is the headline-grabber, the true value for Pyongyang may lie in the ancillary technologies that would logically accompany such a transfer.

- Quieting Technology: A nuclear submarine is only as good as its stealth. Russian submarines, particularly the Akula-class, are renowned for their acoustic quieting. The transfer of advanced silencing mounts, propeller (screw) designs, and hull coating technologies would be arguably as valuable as the reactor itself. A quiet nuclear submarine is a survivable one.

- Systems Integration and Training: Building a reactor into a hull is one thing; making the entire system work reliably and safely at sea is another. Russian assistance would likely extend to design blueprints, operational manuals, and perhaps even covert training, shaving years off North Korea’s learning curve and preventing catastrophic failures.

- A Pattern of Proliferation: This is not without precedent. Russia’s lease of an Akula-class submarine to India provided New Delhi with an invaluable apprenticeship in operating a modern nuclear attack boat. The parallels are striking. The specific Akula-class boat mentioned in reports, the Nerpa (ex-INS Chakra), now reportedly sitting dismantled at the Zvezda shipyard, is a prime candidate for having its propulsion system harvested for Pyongyang. This is a proven playbook, now being run for a far more volatile client.

The Strategic Earthquake: Reshaping Nuclear Deterrence

The deployment of even a single operational North Korean nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) would represent the single most significant advancement in its military capabilities in a generation. Here’s why:

- Survivability of the Second-Strike Force: The core principle of a nuclear triad is that a nation can absorb a first strike and still retaliate. Land-based missiles are vulnerable to a pre-emptive strike. Bombers can be caught on the ground. But a nuclear submarine, hidden in the vastness of the ocean, is the most survivable leg. A North Korean SSBN, powered by a Russian reactor, could deploy for months, lurking silently in the depths of the Pacific. This guarantees a retaliatory strike, making a pre-emptive strike against North Korea an unthinkably risky proposition.

- Holding the U.S. Mainland at Risk from New Vectors: Currently, a North Korean ICBM launch would follow a predictable trajectory over the pole. An SLBM, however, could be launched from the mid-Pacific, drastically reducing flight times to U.S. coastal cities like Los Angeles, Seattle, or San Diego. This complicates missile defense strategies immensely, as threats can emerge from a 360-degree arc.

- A Permanent State of Threat: Unlike a diesel sub that must eventually return to port, a nuclear boat can remain on patrol in a crisis, creating a persistent, undetectable threat. This forces adversaries to maintain a constant, resource-intensive state of high alert, stretching surveillance and ASW assets to their limits.

The Regional Domino Effect

Unsurprisingly, this potential leap in North Korean capability is triggering a regional arms race. The case for South Korea and Japan to acquire their own nuclear-powered submarines, long a topic of debate, has never been more compelling. For South Korea, in particular, which has advanced conventional submarine technology, the next logical step is nuclear propulsion to hunt the new hunters. This would allow it to maintain continuous deterrent patrols and counter the threat of a North Korean SSBN.

Japan, with its pacifist constitution, would face a significant political hurdle, but the strategic imperative is clear. The emergence of a nuclear-armed North Korea with a survivable second-strike capability, backed by a resurgent and increasingly aggressive Russia and a rising China, creates a multi-polar nuclear threat that existing security architectures are ill-equipped to handle.

Conclusion: The Ocean’s Shadow Lengthens

The grand military parade in Pyongyang was a show of force, but the real story is being written not in the open streets, but in the shadowy depths of shipyards and in the clandestine technology transfers between pariah states. The Hwasong-20 on its massive transporter is the threat we can see. The nuclear submarine, enabled by Russian technology, is the threat we cannot see—and that is what makes it so profoundly dangerous.

While it may take Pyongyang several years to operationalize this technology, the fuse has been lit. The strategic balance in Northeast Asia is not just shifting; it is being fundamentally rewritten. The era of the North Korean nuclear submarine, once a distant nightmare scenario, is now looming on the horizon, and its arrival will make the already palpable threat from Pyongyang an enduring, silent, and inescapable feature of the geopolitical seascape.

You must be logged in to post a comment.