The Serpent and the Sleeper: How India’s King Cobras Became Stowaways on the Rail Network

A recent study published in Biotropica reveals that king cobras in western India are inadvertently hitchhiking on freight trains, using the railway network as an unexpected dispersal route from their native Western Ghats habitat into ecologically unsuitable coastal areas like Goa, where rescue records show multiple outliers clustered near rail infrastructure. This accidental transport—likely occurring when snakes enter cargo wagons at night—poses severe consequences for both the reptiles, which face starvation and stress in unfamiliar terrain, and for humans, as India lacks a specific antivenom for king cobra bites that can prove fatal within 15 minutes. Researchers recommend genetic testing, camera traps, and railway hub monitoring to confirm the pattern, emphasizing that linear infrastructure here paradoxically connects rather than fragments habitats, forcing a reevaluation of conservation strategies and public health preparedness.

The Serpent and the Sleeper: How India’s King Cobras Became Stowaways on the Rail Network

There is a specific kind of silence that falls over a railway platform in India when a snake is spotted.

It is not the silence of emptiness, but the sudden, sharp intake of breath from a thousand throats at once. One moment, the station is a symphony of chaos—chai wallahs clinking steel glasses, porters balancing trunks on turbaned heads, the screech of coal engines giving way to the hum of electric locomotives. The next, there is a ripple of movement backward. A pointed stick is produced. The Railway Police Force is called.

Usually, the culprit is a rat snake, displaced from the verges, or a spectacled cobra searching for mice. But recently, in the coastal idyll of Goa, rescuers have started encountering a different kind of passenger: the King Cobra.

Not just any King Cobra, but one that appears to have arrived not by slither, but by sleeper class.

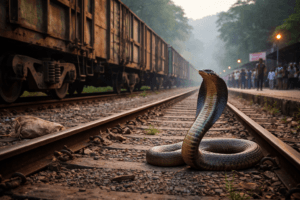

According to a study published in Biotropica, researchers have documented multiple instances of Ophiophagus kaalinga—the world’s longest venomous snake—appearing in ecological zones where they simply should not exist. The common thread? Railway tracks. These snakes aren’t walking there; they are commuting.

This isn’t just a quirky footnote in herpetology. It is a high-stakes game of biological Russian roulette, played out on 68,000 kilometers of steel track, where the loser dies in fifteen minutes, and there is no antidote waiting at the stationmaster’s office.

The Outliers: When the Map Doesn’t Match the Snake

To understand why this is so alarming, you must first understand the King Cobra. Despite its name, it isn’t a true cobra. It is the sole member of its genus, a specialist predator that eats only other snakes. It builds nests for its young. It is intelligent, nervous, and generally avoids humans with an almost clinical precision.

Dr. Dikansh S. Parmar and his team spent two decades compiling snake rescue records across Goa. They ran species distribution models to predict where King Cobras should be. The results were predictable: deep forests, heavy rainfall, the undulating spine of the Western Ghats.

Then came the outliers.

A King Cobra found at Chandor railway station, hiding not in leaf litter, but among concrete railway sleepers and stockpiled steel rails. Another in Vasco da Gama, a port city defined by dry, scrubby vegetation and industrial hum. More in Loliem, Patnem, and Palolem—places where the humidity is too low, the prey base too thin, and the canopy too sparse.

Statistically, these were anomalies. Biologically, they were refugees.

The simplest explanation is not that Goa’s urban coast has suddenly become prime real estate for the world’s largest venomous snake. It is that these animals are taking the train.

The Midnight Express: How a Cobra Boards a Carriage

There is no ticket counter, no platform ticket required. For a snake, boarding a train is an accident of opportunity.

Western India’s railway network is a circulatory system pumping raw materials from the hinterland to the coast. Iron ore from Karnataka and interior Goa is hauled by freight wagons down the gradients of the Western Ghats, through tunnels cut into basalt rock, past sal forests and spice plantations.

At night, these trains idle in yards or slow to a crawl on steep inclines. A King Cobra, hunting for a rat snake drawn to grain spillage, may follow its prey into the undercarriage of a wagon, or into an open container. Once inside, the vibration of the moving train triggers a freeze response. The snake does not attempt to escape the moving metal beast; it hunkers down.

By sunrise, the train has descended 800 meters in altitude. The snake emerges into a world that looks, smells, and feels entirely alien. It is disoriented, stressed, and defensive.

This is not migration. This is involuntary relocation.

The Biology of Accidental Tourists

What happens to a King Cobra that wakes up in Vasco?

The outlook is grim. King Cobras are not generalists like the Common Wolf Snake or the Checkered Keelback. They are dietary specialists. Their primary prey includes rat snakes, pythons, and even other venomous species. If the coastal lowlands lack this specific menu, the cobra faces starvation.

Furthermore, the thermal environment is wrong. The Western Ghats offer thermal refugia—cool, moist microhabitats under dense canopy. Goa’s coastal plains are hotter, drier, and offer limited shelter. A stressed King Cobra forced to thermoregulate in the open is visible to crows, mongooses, and humans.

This is where the conservation paradox bites hardest. The very infrastructure that fragments wildlife habitats in the highlands is accidentally creating “wildlife corridors” leading to dead ends. The snake doesn’t find a new territory; it finds a death trap.

The Human Factor: Fear in the Fast Lane

But while the snake is unlucky, the human who finds it is terrified.

India is home to over a billion people and roughly 3,000 King Cobras in the wild. Bites from this species are rare, but when they occur, the clock ticks faster than for any other snake in Asia. The venom is not the most toxic, but the volume is immense—a single bite can deliver enough neurotoxin to kill an elephant, or a dozen men.

Here is the chilling detail that the study reiterates: India currently has no specific, widely available commercial antivenom for King Cobra envenomation.

Polyvalent antivenom, the standard treatment used for the “Big Four” venomous snakes (Indian Cobra, Russell’s Viper, Saw-Scaled Viper, and Common Krait), is ineffective against King Cobra venom. It does not neutralize the unique three-finger toxins and kunitz-type peptides present in Ophiophagus venom.

If a farmer in rural Goa steps out of his hut at dawn to relieve himself and steps on a King Cobra that fell off a train at 3:00 AM, he has approximately 15 to 30 minutes to live. There is no vial waiting at the primary health center. There is no time to reach Goa Medical College. There is only panic, traditional remedies, and a slow suffocation as his diaphragm paralyzes.

This is the real cost of railway-assisted dispersal. It introduces high-risk venomous species into communities that have no medical defense against them.

The Railway as Ecosystem

To the train driver, the track is a dead thing—steel, wood, and ballast. To a biologist, it is an edge habitat.

Railway corridors in India are rarely sterilized. They are bordered by nalas (drains), overgrown weeds, discarded food waste from passenger trains, and thriving colonies of rodents. This attracts rat snakes. Rat snakes attract King Cobras.

A rail yard is essentially a buffet.

The distinction between “wild” and “urban” collapses when you view the landscape from a snake’s eye level. The railway isn’t a barrier; it is a highway. It connects the Bhagwan Mahaveer Wildlife Sanctuary to the Mormugao Port Trust. It connects the canopy to the cargo hold.

Parmar and his colleagues are not alarmists. They do not suggest that King Cobras are taking over railway stations. They present five verified outliers over two decades. But five is enough to prove a concept. If it has happened five times in documented rescue records, how many times has it happened unnoticed? How many snakes have been killed on sight, their bodies tossed into the bushes, unreported?

A Genetic Whodunnit

The study offers a roadmap for confirmation. The authors call for genetic testing.

If a King Cobra found in Palolem shares mitochondrial DNA haplotypes with a population 80 kilometers north in the Ghats, the case is closed. This would confirm not just dispersal, but origin.

Such testing is not merely academic. It has immediate conservation implications. If snakes in the coastal lowlands are actually “immigrants” rather than a resident breeding population, conservationists can avoid wasting resources trying to “protect” a non-viable urban population. It also allows railway authorities to identify high-risk transfer nodes—specific yards or junctions where snakes are boarding.

Camera traps at freight yards, night surveys during monsoon, and awareness training for railway staff could mitigate both snake mortality and human risk.

The Philosophy of Movement

There is something deeply metaphorical about a King Cobra on a train.

We tend to think of wilderness as static—a map of green blobs connected by faint dotted lines labeled “wildlife corridor.” We imagine leopards using underpasses and elephants walking along designated paths. But wildlife does not read management plans.

A King Cobra does not know it has crossed from a protected area into a industrial zone. It only knows that the vibrations have stopped, and it is time to find cover.

In a rapidly warming world, species will move. They will follow water, follow prey, follow thermal comfort. Sometimes they will follow accidental linear pathways carved by humans. The King Cobra on the railway is a preview of the Anthropocene: a wild creature adapting to human infrastructure not by evolving, but by hitchhiking.

The Ground Reality: What Must Change

The solution is not to stop trains. India’s economy moves on rails. But there are pragmatic interventions available.

First: Antivenom development. The Indian government and research institutions must prioritize the development of a pan-Indian Ophiophagus antivenom. Nepal and Thailand produce King Cobra antivenom, but import logistics are cumbersome. Indigenous production is a matter of public health urgency, particularly as these snakes appear in new geographic zones.

Second: Railway hygiene. Freight yards should be audited for rodent and snake harborage. Clearing dense vegetation immediately adjacent to cargo holding areas could reduce the likelihood of snakes boarding.

Third: Rescue network strengthening. Goa has a relatively robust snake rescue network. Other states along the Western Ghats—Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kerala—must prepare for the possibility of “railway cobras” turning up in unexpected districts. Rescuers need King Cobra handling gear and relocation protocols for coastal habitats.

Fourth: Public communication. Passengers and railway staff should be taught not to kill snakes on sight, but to report them. The typical response to a snake on a train is mob violence against the animal. Shifting this to a rescue-and-release response saves both lives and data.

Conclusion: The Unseen Passengers

The next time you wait for a train in India—perhaps at Kulem, near the Goa-Karnataka border—watch the tracks as they fade into the dark of the tunnel.

If you see a length of brown hose lying perfectly still on the rail, don’t touch it.

It might just be a passenger who boarded in the jungle and hasn’t yet found the exit.

The King Cobra does not understand the concept of a state border, a ticket check, or a terminus. It understands heat, hunger, and vibration. In the 21st century, that vibration increasingly comes from diesel engines and steel wheels.

We built the railways to unite a nation. We never expected they would also unite two Indias—the India of concrete and the India of canopy. Now that they have, we must learn to share the commute.

Because the King Cobra isn’t trying to invade our world. It is just trying to get home. Unfortunately, it keeps ending up at the wrong station.

You must be logged in to post a comment.