The Report That Broke Human Rights Watch: When a Legal Argument on Palestinian Return Became a Third Rail

The Report That Broke Human Rights Watch: When a Legal Argument on Palestinian Return Became a Third Rail

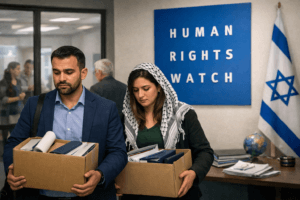

In early 2026, a seismic event rocked one of the world’s most prominent human rights organizations, not from external pressure, but from within. Omar Shakir and Milena Ansari—the entirety of Human Rights Watch’s (HRW) Israel and Palestine team—resigned in protest. The cause: HRW leadership’s last-minute decision to block their report, which argued that Israel’s decades-long denial of Palestinian refugees’ right to return constitutes a crime against humanity. The incident reveals a stark tension between principled legal advocacy and political pragmatism, exposing a critical boundary in the international discourse on Israel and Palestine.

This was not a report rushed to publication. Titled ‘Our Souls Are in the Homes We Left’: Israel’s Denial of Palestinians’ Right to Return and Crimes Against Humanity, the 33-page document was seven months in the making. It had navigated HRW’s rigorous internal “pipeline,” receiving approvals from eight separate departments, including specialists, the legal division, and regional offices. It was fully coded to their website, translated, and accompanied by a vetted press release. Partners had been briefed for its scheduled release on December 4, 2025.

The decision to “pause” it just days before publication, as new Executive Director Philippe Bolopion began his tenure, sparked an internal firestorm. More than 200 staff members signed a protest letter, warning that circumventing the established review process threatened the very cornerstone of HRW’s credibility.

The Novel Legal Argument: “Other Inhumane Acts”

The heart of the controversy was the report’s legal conclusion. While HRW has consistently supported the Palestinian right of return in past publications, this report broke new ground by seeking to legally define its denial as a specific crime against humanity known as “other inhumane acts”.

This category, defined in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), is designed to address grave abuses that cause “great suffering” comparable to crimes like apartheid or extermination but don’t precisely fit those definitions. The researchers built their case on a precedent: a 2018 ICC pre-trial finding that determined preventing Rohingya refugees from returning to Myanmar could be prosecuted under this same category. Shakir saw this as moving a powerful legal argument from academia into the practical toolkit of human rights advocacy, potentially providing a pathway for legal accountability for refugees displaced as far back as 1948.

The Core of the Disagreement: Law vs. Perception

Publicly, HRW leadership framed the block as a matter of methodological rigor. In a statement, they said aspects of the research and factual basis for legal conclusions “needed to be strengthened to meet HRW’s high standards”. Bolopion called it a “good-faith disagreement among colleagues on complex legal… questions”.

Internally, however, a different concern surfaced: fear of political backlash and reputational damage. Senior officials worried the report would be misconstrued as a challenge to Israel’s existence as a Jewish state. Chief Advocacy Officer Bruno Stagno Ugarte wrote in an October email that he feared detractors would read the findings “as a call to demographically extinguish the Jewishness of the Israeli state”. Acting Program Director Tom Porteous questioned “how we are going to deploy this argument… without this coming off as HRW rejecting the state of Israel”.

This anxiety points to the unique third-rail status of the right of return. As Shakir noted, while terms like apartheid, genocide, and ethnic cleansing have entered mainstream discussion on Israel, advocating for the return of millions of Palestinian refugees and their descendants to their former homes remains the most politically charged issue of all. Israel and its supporters argue that implementing this right would end the Jewish majority in Israel, fundamentally altering the state’s character.

A Fractured Institution and a Contested Precedent

The resignations exposed deep fissures within HRW. The mass staff protest letter argued that blocking a fully vetted report “undermine[s] trust in its purpose and integrity” and “set a precedent that work can be shelved without transparency”. Shakir and Ansari argued that leadership’s proposed “fix”—limiting the crime against humanity finding only to Palestinians displaced since 2023 from Gaza and the West Bank—was legally incoherent. It would mean, Shakir wrote, that a Palestinian displaced for one year suffers a crime against humanity, but one denied return for 78 years does not.

Former Executive Director Kenneth Roth defended the block, arguing Shakir tried to “fast-talk through the review system… an extreme interpretation of the law that was indefensible”. Yet, Shakir countered that the same legal reasoning on “other inhumane acts” had been endorsed by HRW’s legal team in prior reports, such as one on the displacement of the Chagossian people.

The Broader Context: An Escalating Pattern of Displacement

The blocked report sought to connect historical trauma with current events. It was inspired by interviews with Gaza refugees in late 2024 who linked their plight to the “generational trauma of being uprooted… back in 1948 and back in 1967”. This analysis fits a pattern HRW itself has forcefully documented elsewhere. Just months before, in November 2025, HRW published a major report detailing how Israeli forces’ early-2025 evacuation and demolition of three West Bank refugee camps (Jenin, Tulkarem, and Nur Shams), displacing 32,000 people, constituted war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The unpublished report aimed to draw a through-line from the 1948 Nakba—the catastrophic displacement of over 700,000 Palestinians—to these ongoing acts. It documented not only recent displacements but also the persistent suffering of refugees in Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria, who face poverty, substandard housing, and severe legal restrictions.

The Stakes: Credibility, Law, and the Future of Advocacy

This crisis presents a fundamental question for human rights organizations: where is the line between prudent strategy and a compromise of principle? The debate within HRW mirrors a wider tension in international law and diplomacy. The right of return is firmly established in international law, articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 13) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. For decades, the United Nations has reaffirmed this right for Palestinian refugees.

However, its implementation is arguably the most intractable issue in the conflict. By moving the discussion from a political right to a prosecutable crime, the report threatened to fundamentally shift the debate.

The table below summarizes HRW’s public stances on key legal terms regarding Israel/Palestine, highlighting the exceptional nature of the blocked report’s conclusion:

| Legal Term/Issue | HRW’s Public Stance & Use | Status & Context |

| Apartheid | Formally applied in a landmark 2021 report, accusing Israel of the crime against humanity of apartheid. | Now part of mainstream discourse; used by other major NGOs and UN bodies. |

| Right of Return | Consistently supported as a human right in publications (e.g., 2023 Nakba dispatch). Official organizational policy. | Supported in principle, but its denial had not previously been labeled a specific crime against humanity by HRW. |

| “Other Inhumane Acts” (CAH) | Legal category used in other contexts (e.g., Chagos Islands report). | The novel argument of the blocked report was applying this to the denial of the right of return for Palestinians. |

| Genocide & Extermination | In late 2024, HRW stated Israeli actions in Gaza made authorities “responsible for… acts of genocide” and the crime against humanity of “extermination”. | Used in context of the war in Gaza post-October 2023. |

| Forced Displacement (Current) | Regularly documented as a war crime and crime against humanity (e.g., West Bank 2025 report). | Applied to ongoing, mass displacement events. |

Ultimately, the resignations of Shakir and Ansari signify more than an internal dispute. They highlight a critical moment where the evolving boundaries of human rights discourse met institutional caution. The researchers argued that bearing witness to historical and ongoing suffering requires applying the law consistently, even—or especially—when it leads to politically inconvenient conclusions. HRW leadership, facing a transition and fearing a potentially devastating backlash, opted for what it saw as strategic pause.

The fallout leaves the organization’s credibility questioned by some of its own staff and the wider human rights community. It also leaves unresolved the central, painful question posed by the report’s intended interviewees, whom Shakir quoted in his resignation: They deserve to know why their stories aren’t being told. As the legal, political, and moral dimensions of the Palestinian right of return continue to collide, this episode serves as a stark marker of how intensely contested the path to justice remains.

You must be logged in to post a comment.