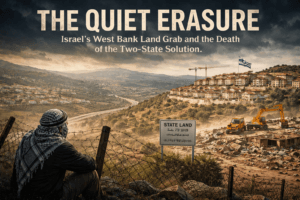

The Quiet Erasure: Israel’s West Bank Land Grab and the Death of the Two-State Solution

The Quiet Erasure: Israel’s West Bank Land Grab and the Death of the Two-State Solution

For decades, the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians has been a story of high-drama flashpoints: wars, intifadas, and high-stakes diplomatic summits. But on a quiet Sunday in February 2026, the Israeli government approved a bureaucratic process that may prove more transformative—and more permanent—than any military campaign. The decision to reopen official land registration in the West Bank for the first time since the 1967 war is not just another political squabble; it is the methodical, legalistic groundwork for cementing Israeli control over territory the Palestinians envision for their future state.

To the casual observer, a cabinet decision to authorize a “land registration process” sounds arcane, buried in the weeds of administrative law. But in the charged landscape of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, land is the most potent currency. This move, spearheaded by the most far-right government in Israeli history, transforms a temporary occupation into a permanent acquisition, one deed at a time.

The Paper Trail of Conquest: What “Land Registration” Really Means

The Israeli ministers who proposed the plan—Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, Justice Minister Yariv Levin, and Defense Minister Israel Katz—frame the decision as a matter of efficiency and legal clarity. Their joint statement argues that it will allow a “transparent and thorough clarification” of property rights. On its face, the premise is technically true. The West Bank’s land records are a palimpsest of competing claims, layered with Ottoman-era titles, British Mandate maps, and Jordanian property laws from the period between 1948 and 1967. It is a fragmented and often ambiguous system that invites dispute.

However, context is everything. By authorizing the Israeli-run Land Registry and Settlement of Rights—a body under the Justice Ministry—to systematically register land as “state property,” the Israeli government is effectively acting as the sovereign over territory that the vast majority of the international community considers occupied. This is not a neutral administrative act. It is a profound political declaration.

For the first time since 1967, a formal mechanism is being put in place to declare, survey, and catalogue land in Area C of the West Bank (the roughly 60% of the territory under full Israeli military and civil control) as belonging to the State of Israel. Once land is registered as “state land,” it becomes exceedingly difficult for Palestinians to claim ownership. More importantly, it becomes available for exclusive Israeli use, almost invariably for the construction and expansion of Jewish settlements.

The Ideological Engine: Smotrich’s Vision of a “Sterile” West Bank

To understand the gravity of this decision, one must look at the man driving it. Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, a settler leader himself, has long been transparent about his goals. He openly calls for the “application of Israeli sovereignty” over the West Bank and has worked tirelessly to undermine the Palestinian presence there. For Smotrich and his ilk, this land registration project is the most powerful tool in their arsenal. It is the quiet, bureaucratic arm of annexation.

This isn’t about security or historical rights in the abstract. It is about creating facts on the ground that are irreversible. By formally registering land as Israeli state property, the government achieves several strategic goals simultaneously:

- Legitimizing Settlements: Existing settlements, often built on land with contested ownership, can be retroactively legalized under Israeli law. New settlements can be planned and constructed on land now classified as “state land” without the legal quagmire of proving purchase or ownership.

- Crippling Palestinian Development: Area C, which is rich in natural resources and agricultural land, is the only contiguous territorial expanse the Palestinians would need for a viable state. By formally claiming this land, Israel prevents any Palestinian construction or development, confining Palestinian population centers to the fragmented enclaves of Areas A and B.

- Preempting a Two-State Solution: A future Palestinian state requires land. By systematically transferring the ownership of that land from a disputed status to “Israeli state property,” the government is preemptively dismantling the territorial foundation upon which any peace agreement would be built.

A Palestinian Response: From Condemnation to Resistance

The reaction from Ramallah was swift and despairing. The Palestinian Presidency, led by Mahmoud Abbas, issued a statement through the official WAFA news agency, calling the move a “dangerous escalation” and a “de facto annexation.” Their plea to the international community to enforce international law, specifically UN Security Council Resolution 2334 (which unequivocally states that Israeli settlements have “no legal validity and constitute a flagrant violation under international law”), felt like a ritualistic incantation—a hope that words on a UN document could somehow counter the bulldozers and land surveyors on a hilltop.

The statement’s assertion that “measures will not grant the Israeli occupation legitimacy” is a powerful declaration of defiance, but it masks a deeper sense of powerlessness. For the average Palestinian villager living near a settlement in the Jordan Valley or the South Hebron Hills, this decision is not abstract. It is the knock on the door. It is the military order declaring their ancestral grazing land, which their family has farmed for generations under Ottoman and Jordanian rule, to be “state land” because they lack the modern, Israeli-recognized paperwork to prove it.

Hamas, which controls Gaza, responded with its characteristic fire, describing the decision as “null and void” and vowing to resist. Their language of “Judaizing” the land and vowing to resist “by force” plays into the narrative of the Israeli far-right, which uses such threats to justify its maximalist policies. Yet, Hamas’s statement also taps into a growing sentiment among Palestinians across the political spectrum: that the international community’s words are meaningless, and that only resistance—whether diplomatic, popular, or armed—can protect their remaining rights.

The Human Toll: The Village That Might Disappear

To put a human face on this bureaucratic decision, consider a hypothetical, yet representative, community: the small herding village of Khirbet al-Marah, nestled in the hills south of Nablus. Its residents are part of a semi-nomadic Bedouin community that has moved through these valleys for centuries. Their claim to the land is not written on an Ottoman deed but is etched into the oral history of their clans, the stones of their ancient wells, and the graves of their ancestors.

Under the new registration process, a village like Khirbet al-Marah faces an existential threat. When Israeli surveyors arrive, they will consult a central database. Without a formal deed filed with a modern registry, the land will likely be classified as “state land.” The villagers, who may not have the resources to hire an Israeli lawyer or navigate a complex legal system in Hebrew, will have a limited time to file an objection. If they fail, their land is gone. Soon after, a notice may arrive declaring their homes “illegally built on state land,” making them subject to demolition—a fate that has befallen countless similar communities.

This is the “quiet transfer.” It doesn’t always require the drama of soldiers forcibly removing families. It can be done with clipboards, legal notices, and the stroke of a pen in a government office in Jerusalem. The land is then allocated to a nearby settlement, which gets a new neighborhood with green lawns and red roofs, built on the ruins of a pastoral way of life.

The International Community: Complicity in Inaction

The Palestinian call for international intervention echoes in a familiar vacuum. While the European Union and the United States (depending on the administration) routinely issue statements “reaffirming their commitment to a two-state solution” and expressing “deep concern” over settlement expansion, these are rarely backed by tangible consequences.

The Biden administration, for instance, reversed the previous administration’s more lenient policies on settlements but stopped short of imposing meaningful sanctions on Israel or its officials. The decision to reopen land registration is a direct test of this resolve. It is a move that fundamentally alters the status quo, not just maintaining it.

By authorizing this process, the Israeli government is betting that the international community will once again issue condemnations that are promptly forgotten. They are betting that trade deals, security cooperation, and the inertia of diplomacy will trump the enforcement of international law. The tragedy for the Palestinians is that this bet has paid off for decades. Resolution 2334, passed in 2016 with great fanfare, explicitly called on states to “distinguish, in their relevant dealings, between the territory of the State of Israel and the territories occupied since 1967.” This was a clear call to stop trading with settlements. It has been almost universally ignored.

Conclusion: The End of the Roadmap

The decision to reopen land registration in the West Bank is a milestone. It marks the moment when the Israeli government stopped merely expanding settlements and began formally claiming the land itself. It signals that for the current ruling coalition, the “peace process” is over. They are not interested in negotiating over the land; they are interested in owning it.

For Palestinians, it is a devastating confirmation that their dream of statehood is being systematically foreclosed, not by war, but by a slow-moving administrative machine. The land that was to be the heart of their future nation is being quietly registered as someone else’s property.

As the Land Registry and Settlement of Rights gears up with its “dedicated staff and budget,” it is not just mapping territory; it is drawing the final borders of a conflict. It is drawing a map where the Palestinian state has been replaced by isolated, non-contiguous enclaves, surrounded by land that legally belongs to Israel. The two-state solution, already on life support, may have just been handed its death certificate—signed, sealed, and delivered by a land registry office. The only question that remains is what will rise from its ashes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.