The Phantom Chill: Why North India’s February Cold Snap is More Than Just a Forecast

The Phantom Chill: Why North India’s February Cold Snap is More Than Just a Forecast

There is a specific kind of silence that descends upon the Indo-Gangetic plains in mid-February. It isn’t the oppressive, bone-numbing quiet of a January fog, nor is it the bustling anticipation of March harvests. It is the silence of a season holding its breath—unsure whether to retreat or to charge one last time.

As a Western Disturbance makes its eastward trek across the Himalayas, India is currently witnessing exactly that: winter’s last stand.

While the news feeds are buzzing with headlines about “minimum temperature drops” and “cold wind alerts,” the reality settling over Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi is far more nuanced. This isn’t the return of the “cold wave” that forces schools to close and trains to run late. Instead, it is something rarer, more beautiful, and deeply evocative: the phantom chill of late winter.

The Geography of a Dying Winter

To understand what is happening outside your window right now, you have to look up—specifically, to the snow-clad Pir Panjal range.

The Western Disturbance currently influencing the weather is a relatively feeble system. Unlike its December counterparts, which carry heavy moisture and wage war with the remnants of the Siberian High, this disturbance is dry and moving fast. It is acting less like an invader and more like a bellows, fanning the cold air that has settled over the mountains down into the river plains.

This is why, despite the drop in mercury, the sun remains victorious during the day. In cities like Ludhiana and Kanpur, farmers are not halting the sowing of summer crops. In Delhi, the chaiwallahs are noticing that while they are doing brisk business in the early mornings, the afternoon crowds are asking for cold drinks again.

This duality is the signature of February. It is a month where the wardrobe becomes a battlefield—heavy woolens in the morning, light cotton by 2 PM.

The City That Forgot How to Be Cold

Take Delhi-NCR, for example. The national capital has endured a bizarre winter in 2025-26. December was relatively mild, January brought a few sharp spikes of cold, but the season never really “settled” the way it did a decade ago.

Now, the city is experiencing what meteorologists call a “compensatory chill.” The air quality, which remained hazardous for much of January due to stagnant conditions, has improved dramatically. The return of cold northerly winds has scrubbed the sky clean. For the first time in weeks, the Delhi Ridge looks green under the sun, and the Yamuna’s haze has lifted.

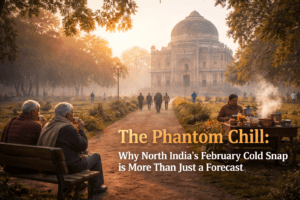

But here is the human insight that data often misses: nobody in Delhi minds this cold. There is a collective exhale happening. After months of debating air purifiers and enduring toxic fogs, residents are stepping out. The morning walkers in Lodhi Garden are back in full force. The golf courses are busy. This cold snap is not a disaster; it is a reprieve.

The Himalayan Trickle-Down Effect

The weather pattern unfolding across North India is a classic example of atmospheric trickle-down economics. When the Western Disturbance passes over Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh, it doesn’t just dump snow; it reconfigures the wind corridors.

As the system moves east, it pulls air from the cold interior of Central Asia. This air mass moves over the Tibetan Plateau and descends into the Indian plains. Physically, this air is dense. It hugs the ground. It flows through the narrow corridors of river valleys.

This is why the chill is most acutely felt in Bihar and Jharkhand—states that are geographically positioned to receive the tail-end of these winds without the insulating effect of urban heat islands. In places like Muzaffarpur and Ranchi, the drop in temperature is subtle on the thermometer but sharp on the skin.

Residents there describe it as “thandak” rather than “sardi”—a coolness rather than bitter cold. It’s the kind of weather that makes you pull the quilt up to your chin at 4 AM, but leaves you comfortable enough to throw it off by sunrise.

The Silence of the Bay of Bengal

Meanwhile, 1,500 kilometers to the southeast, meteorologists are keeping an eye on a developing low-pressure area over the Bay of Bengal.

In any other month, this would be a recipe for cyclogenesis or heavy pre-monsoon rains. But February is the ocean’s quiet month. The sea surface temperatures, while warm enough to sustain clouds, lack the furious convective energy required to generate storms.

What this system will do, however, is create a tug-of-war in the upper atmosphere. As the easterly winds from the Bay of Bengal push westward, they will meet the cold northwesterlies blowing down from the Himalayas. This convergence zone usually sits over Madhya Pradesh or Vidarbha.

The result? Coastal Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu might see some high, wispy clouds drifting inland. They look dramatic at sunset, but they carry no rain. For the farmer in interior Maharashtra, this means nothing changes. For the fisherman in Chennai, it means a slightly choppier sea, but nothing to keep the boats docked.

Living Through the “Pleasant” Zone

The most used word in the current India Meteorological Department (IMD) bulletins is “pleasant.” It is a dangerous word, because it implies passivity. But for the millions living in the vast arc stretching from Rajasthan to West Bengal, this weather is active.

In the mustard fields of Alwar and Bharatpur, the cooler nights are actually beneficial for the late-sown varieties. In the sugarcane belts of western Uttar Pradesh, the lower dew points mean less fungal growth on the crops.

For the urban middle class, this is the brief window where “AC vs. Open Window” ceases to be a debate. The window wins. Power grids get a break. Street vendors selling hot momos and garam jalebis see a surge in evening customers, not because people need to warm up, but because the air outside is finally inviting enough to linger.

A Practical Guide to the Next 72 Hours

If you live in the affected regions, here is what the next three days actually look like on the ground:

Early Morning (4 AM – 7 AM): This is the coldest window. Motorcycle riders in Noida, Ghaziabad, and Faridabad should expect windscreens to be misted over. It’s not dense fog, but a thin film of moisture. Keep your headlights dipped and your speed steady.

Late Morning (9 AM – 11 AM): The sun burns off the chill quickly. Layering is key. A hoodie or a light jacket worn at 7 AM will feel cumbersome by 10 AM. Thermal inners may be overkill unless you are in the open plains of Haryana.

Afternoon (1 PM – 4 PM): Almost summer-like in appearance, but not in intensity. The UV index is moderate. It is safe to sit in the sun. This is the perfect time for drying winter-stored woolens before packing them away.

Evening (6 PM onwards): The temperature falls like a stone. Unlike December, where the cold builds gradually, February evenings experience a rapid heat loss. If you are commuting home, the temperature drop between 5:30 PM and 7 PM can be as much as 6 to 8 degrees Celsius.

The Emotional Weather Report

India has a complicated relationship with winter. In a tropical country, cold weather is often viewed as a luxury—a break from the punishing heat. But the winter of 2025-26 has been stingy.

This particular spell, therefore, carries emotional weight. It feels like a gift. It is the season apologizing for its absence. On social media, the trend is not complaints about the “return of cold,” but nostalgia. People are posting photos of piping hot tea and sunlit balconies. They are taking their elderly parents out for walks. They are sitting on their rooftops in Lucknow and Patna, wrapped in shawls, looking at stars that have reappeared after weeks of haze.

This is the untold story of the weather update. The data points to a drop in minimum temperature. The headlines warn of a “Western Disturbance.” But the reality is softer, slower, and far more human.

Looking Ahead: The Calm Before the Heat

As this Western Disturbance moves away toward Nepal and the northeastern states, the cold air mass will weaken. By February 16 or 17, the northerly winds will subside. The minimum temperatures will begin their inevitable march upward.

March is waiting in the wings. By the first week of March, the jet stream will shift northward, and the Western Disturbances will start bringing pre-monsoon rains—thunderstorms, dust storms, and hailstorms that mark the violent end of the Indian winter.

So, if you are reading this in Delhi, Jaipur, or Varanasi, step outside tonight. The air has that rare edge to it—sharp enough to remind you that winter exists, but gentle enough that you don’t want to run from it.

It won’t last. It isn’t supposed to. But while it does, it is the very definition of perfect weather.

You must be logged in to post a comment.