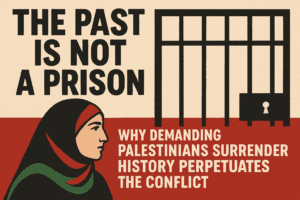

The Past is Not a Prison: Why Demanding Palestinians Surrender History Perpetuates the Conflict

The central argument against the prevailing narrative is that peace cannot be achieved by demanding Palestinians surrender their history and right of return, a framing that wrongly pathologizes their struggle as a refusal to “accept reality” while ignoring the root cause: Israel’s ongoing occupation, settlement expansion, and an apartheid-like regime that perpetuates their displacement.

This demand creates a profound moral asymmetry, where Israel’s historical trauma is sacred yet Palestinian remembrance of the Nakba is deemed an obstacle, forcing them to forget a past that the present-day structures of military control and mass incarceration constantly make them relive. True peace, therefore, requires not historical amnesia but an end to the occupation and the establishment of a political future built on dignity, equality, and justice for both peoples.

The Past is Not a Prison: Why Demanding Palestinians Surrender History Perpetuates the Conflict

The most enduring myths are often those dressed as pragmatism. In the long and tortured history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, one of the most persistent narratives is that peace is hostage to a Palestinian refusal to “accept reality.” The argument, a staple of diplomatic circles and opinion pages, suggests that Palestinians must finally relinquish what is often framed as a “dangerous illusion”—the hope for a right of return, the memory of the Nakba, the belief that a fundamentally unjust status quo is not permanent.

This framing is seductive in its simplicity. It reduces a century of colonial dispossession, military occupation, and systemic inequality to a matter of psychological adjustment. The burden of peace, it implies, falls on the occupied to forgive, forget, and move on. But to demand that a people surrender their history is not to pave the way for peace; it is to demand their spiritual and cultural capitulation. The true obstacle to a just and lasting peace is not a people clinging to the past, but a political and military regime that forces them to relive it every day.

The Weight of Living History

To speak of Palestinian “memory” is not to speak of a distant, abstract nostalgia. For the Palestinian people, history is a material and lived experience. A family displaced from Jaffa or Haifa in 1948 does not inhabit a myth; they inhabit the concrete confines of a refugee camp in Lebanon, the crowded alleyways of Gaza, or the precariousness of East Jerusalem, where statelessness and restricted movement are daily realities.

This history is not a static event but a continuous process. The homes lost in 1948 were followed by lands annexed in 1967, which are now being eclipsed by the relentless expansion of illegal settlements. A child in Khan Younis who has seen her home reduced to rubble multiple times is not clutching at an imagined grievance. She is enduring the latest chapter in a political order that has consistently treated her people’s presence on the land as negotiable, and their lives as collateral.

The staggering human toll of recent conflicts, as cited in the original piece, is not merely a statistic of war but a testament to this profound imbalance of power. When over 20,000 children are killed, when 90% of a population is displaced, and when the infrastructure of life—homes, schools, hospitals—is systematically dismantled, it does not create a blank slate for a new beginning. It etches trauma deeper into the collective psyche, reinforcing the very historical narrative that Palestinians are supposedly being asked to abandon.

The Flawed Analogy: Selective Amnesia as a Peace Plan

Proponents of the “surrender history” thesis often draw parallels to post-World War II Europe. They point to the millions of ethnic Germans expelled from Eastern Europe who, we are told, “moved on” for the sake of peace. The lesson is presented as clear: acceptance is the price of stability.

This analogy, however, is profoundly misleading. The stability achieved in Europe was not built solely on the forced amnesia of displaced populations. It was built on a foundation of mutual recognition of sovereignty, the cessation of violent conquest, and the political and economic integration of a defeated Germany. Crucially, the process was concluded; the chapter was closed.

For Palestinians, none of these conditions apply. Their displacement is not a concluded historical event but an ongoing reality. The occupation, deemed unlawful by the International Court of Justice, continues. The settlement project, illegal under international law, expands daily. The demand, therefore, is not for Palestinians to accept a fait accompli but to legitimize a process that is still actively erasing their presence from the map. It is the difference between being asked to accept the outcome of a finished race and being asked to cheer for the opposing team while you are still forced to run it.

The Colonial Double Standard: Remembering and Forgetting

The most striking feature of this narrative is its stark moral asymmetry. It places the entire burden of accommodation on the occupied, while the occupier is free to demand recognition of its own narrative and permanence.

Israel’s national identity is rightly built upon the sacred imperative to remember the Holocaust and centuries of Jewish persecution. This remembrance is understood as a non-negotiable pillar of survival and identity. Yet, when Palestinians engage in the same act of remembrance—honoring the Nakba (“catastrophe”) of 1948—it is framed as a radicalizing threat, an obstacle to peace. In 2009, this double standard was made explicit when the Israeli education ministry attempted to ban the term “Nakba” from textbooks for Arab children.

This is the essence of a colonial mindset: the history of the powerful is sacred, while the history of the subjugated is disposable. It says that our trauma justifies our state, but your trauma is an inconvenient fiction you must discard.

The Architecture of Enforced Amnesia

This demand to forget is not merely rhetorical; it is enforced through a tangible architecture of control. The system of checkpoints, the separation barrier weaving through the West Bank, the ID systems that dictate movement, and the legal distinction between Jews and Palestinians in the occupied territories have been widely described by leading human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as a system of apartheid.

At the heart of this system lies the practice of mass incarceration. As noted, Israel holds nearly 10,000 Palestinians as political prisoners, with about one in five Palestinians having been imprisoned since 1967. This is not merely a security measure; it is a tool of social fragmentation and political suppression. When a significant portion of a population, including children, passes through a prison system where many are held without trial, it creates a generational inheritance of trauma and control. It is a mechanism designed to break the will and disrupt the social and political continuity necessary for collective identity and resistance.

A Path Forward: Dignity in the Present, Not Surrender of the Past

Genuine, sustainable peace cannot be built on a foundation of historical denial and imposed amnesia. Peace requires structures that make dignity possible in the present. This means:

- An End to the Occupation: A full withdrawal from the territories occupied since 1967, as demanded by numerous UN resolutions, is the non-negotiable starting point. Sovereignty cannot be partial.

- Equality Before the Law: Whether in a future Palestinian state or in a single, binational state, the principle of equal rights for all citizens, regardless of ethnicity or religion, is paramount. The current apartheid-like legal hierarchy must be dismantled.

- Acknowledgment and Justice for Refugees: The Palestinian right of return is one of the most intractable issues, but it cannot be resolved by simply demanding it be forgotten. It must be addressed through acknowledgment, and a serious, internationally-backed process that considers creative solutions including return, resettlement, and compensation, as called for by UN General Assembly Resolution 194.

- Mutual Recognition of Suffering: Just as the world recognizes the profound trauma of the Holocaust, the historical truth of the Nakba and the ongoing suffering of the Palestinian people must be acknowledged by Israel as a necessary step toward reconciliation.

To argue that peace requires Palestinians to surrender their history is not pragmatism; it is a moral abdication that clothes a cruel and unequal status quo in the language of realism. The tragedy of Palestine is not that its people refuse to let go of the past, but that the structures of the present constantly force them to live in it. A future of peace will only become possible when both peoples are free to remember their pasts without being imprisoned by them, and when the present offers a dignity that makes the future worth embracing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.