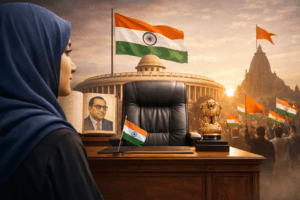

The Hijab, The Constitution, and The PM’s Chair: A Debate Revealing India’s Identity Crossroads

Explore the fierce debate: Can a hijabi woman be India’s PM? Dive into the clash between constitutional secularism & political reality. Read more.

The Hijab, The Constitution, and The PM’s Chair: A Debate Revealing India’s Identity Crossroads

The statement was brief, but its echoes are likely to reverberate through India’s political and social landscape for some time. At a rally in Solapur, Asaduddin Owaisi, the MP and president of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), articulated a vision that is both constitutionally mundane and politically explosive: “It is my dream that a day will come when a hijab-clad daughter will become the Prime Minister of this country.”

This wasn’t merely a political aspiration; it was a pointed rhetorical device. By invoking Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s Constitution, Owaisi framed his dream as the ultimate test of Indian secularism—a living testament to the document’s promise that every citizen, regardless of religion or gender, has an equal right to the nation’s highest office. His subsequent contrast with Pakistan, whose constitution reserves the prime ministerial office for a Muslim, was a deliberate move to position India’s pluralism as superior to its neighbour’s theocratic identity.

However, the swift and layered reactions from across the political spectrum reveal that Owaisi’s dream touches the rawest nerves in contemporary Indian polity. It has ignited a complex debate that sits at the intersection of constitutional law, majoritarian politics, symbolic representation, and the everyday realities of Muslim women in India.

Deconstructing the Dream: More Than a Political Slogan

To understand the weight of Owaisi’s statement, one must look beyond the headline. His speech wove together several critical threads:

- Constitutional Literalism vs. Lived Reality: Owaisi anchored his argument in the absolute letter of the law. Article 14 guarantees equality before the law, and the Constitution places no religious or gendered barrier on the office of the Prime Minister. His remark was a challenge: Do we believe in these principles only in theory, or also in their most profound, visible manifestations? The hijab, a potent symbol of faith and identity for many Muslim women, becomes the test case. Can a nation embrace a leader whose most visible identity marker is that of a religious minority?

- A Mirror to Pakistan: The Pakistan comparison is a classic rhetorical strategy in Indian secular discourse. It serves a dual purpose: it appeals to national pride by positioning India’s framework as more inclusive, while simultaneously issuing a warning. The underlying message is clear—straying from this secular commitment towards majoritarian exclusivity would mean mirroring the very neighbour India often defines itself against.

- A Response to Majoritarian Rhetoric: The remark did not occur in a vacuum. It comes amid a sustained political and social discourse where Muslim identity, and particularly visible markers like the hijab, have been politicized and often cast as “other.” Owaisi’s vision is a direct counter-narrative. It reclaims the hijab not as a symbol of separatism but as one of belonging and potential leadership within the Indian mosaic.

The Reactions: A Spectrum of Political Worldviews

The responses to Owaisi’s comment form a perfect snapshot of India’s current political ideologies.

The BJP’s Pragmatic Counter-challenge: The BJP’s retort, delivered by spokesperson Shehzad Poonawalla, was tactical. By challenging Owaisi to first appoint a Pasmanda (backward class) Muslim or a hijab-clad woman as president of his own party, the BJP attempted to shift the focus from constitutional principle to political practice. This move aims to frame Owaisi’s statement as hollow symbolism, a case of failing to practice what he preaches. It questions his commitment to intra-Muslim social reform and women’s leadership within his own domain.

The Civilizational Majoritarian View: Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s response was the most ideologically direct. He drew a sharp line between the constitutional and the civilizational. “Constitutionally, there is no bar… But India is a Hindu nation with a Hindu civilisation, and we strongly believe that the Prime Minister of India will always be a Hindu.” This statement lays bare a fundamental tension in modern India. It posits that legal possibility is overridden by a deeper, civilizational truth—that the nation’s ethos and its ultimate political expression are inherently Hindu. In this worldview, secularism means equal rights for minorities, but not necessarily equal symbolic ownership of the nation’s pinnacle identity.

The Meritocratic & Status Quo Argument: Shiv Sena’s Shaina NC offered a different perspective, focusing on merit and current political reality. Her “no vacancy” quip underscored Narendra Modi’s entrenched popularity. More significantly, her call for a future woman PM to be chosen based on “good work and the popular mandate… not caste, creed, or community” represents a common liberal-conservative position. It prioritizes individual merit over group identity, but critics argue this can often be a guise for maintaining the de facto status quo, where the unmarked default candidate (often upper-caste, Hindu, and male) is seen as “merit-based,” while others are seen as “identity-based.”

The Core Question: What Does True Inclusion Look Like?

This controversy transcends the specific image of a hijabi Prime Minister. It forces a national conversation about the hierarchy of belonging.

- Is India’s secularism merely about the freedom to practice religion privately, or does it extend to the right to embody one’s faith publicly in the most prominent spheres, including its highest office?

- Can a nation be a genuine union of states and peoples if certain identities are deemed culturally or civilizationally incompatible with its supreme leadership?

- Is the path to power for marginalized groups solely through deracination—shedding visible markers of identity to assimilate into a majoritarian norm?

For many Muslim women, the hijab is not just a piece of cloth; it is an integral part of their identity, faith, and in many cases, their empowerment. To demand its removal as a precondition for national leadership is to demand they fragment themselves. Owaisi’s statement, whether seen as a sincere dream or political theatre, pushes this uncomfortable question to the fore.

Conclusion: A Dream as a Diagnostic Tool

Asaduddin Owaisi may or may not ever see his dream realized. That is almost beside the point. The power of his statement lies in its function as a diagnostic tool for India’s democratic health.

The fierce reactions it provoked demonstrate that the idea strikes at the heart of competing visions for India: a constitution-first, pluralist republic versus a civilization-state with a dominant cultural core. The journey from legal possibility to lived reality for a hijabi woman—or anyone from a minority community—aspiring to the PM’s chair is paved not just with electoral arithmetic, but with the nation’s willingness to reimagine its own iconography.

The debate is not about a future election; it is about the present character of the nation. It asks: In India’s evolving story, is the highest office a symbol of the majority’s trust, or is it a testament to the confidence of all its people? The answer remains a work in progress, fought over in rallies, on social media, and in the quiet, steadfast convictions of millions. Owaisi’s dream has, once again, laid that battle bare.

You must be logged in to post a comment.