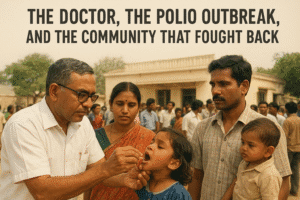

The Doctor, The Polio Outbreak, and The Community That Fought Back

In the 1960s, Dr. T. Jacob John discovered a critical flaw in India’s fight against polio: the standard oral vaccine was failing to protect children. His warnings of its low efficacy were met with governmental inaction, compounding a public health crisis. A catastrophic policy error then unfolded, as the nationwide immunization program administered DPT vaccines without the protective polio shot, inadvertently triggering a massive outbreak that paralyzed nearly 200,000 children. Frustrated by bureaucratic inertia, Dr. John pioneered a radical community-based solution in Vellore.

He orchestrated a localized “pulse polio” campaign, mobilizing volunteers to vaccinate every child in a short, intense burst. This grassroots effort was a monumental success, proving the virus could be stopped. The Vellore model’s triumph provided the essential blueprint for India’s eventual nationwide victory over polio, demonstrating that change often begins with relentless individuals and empowered communities.

The Doctor, The Polio Outbreak, and The Community That Fought Back

In the late 1960s, a sharp-eyed paediatrician in Vellore named Dr. T. Jacob John noticed something disturbing. In his clinic at the Christian Medical College, a handful of children were developing polio. This, in itself, was tragically common in a country reporting 500 new cases of the crippling disease every single day.

The alarming part was their medical history. Each child had received the recommended three doses of the oral polio vaccine (OPV). They were supposed to be protected. Dr. John’s curiosity ignited a lifelong mission that would eventually help reshape India’s public health destiny, but not before confronting a perfect storm of scientific mystery, governmental neglect, and a devastating man-made crisis.

This story, detailed in Ameer Shahul’s new book Vaccine Nation: How Immunization Shaped India, is more than a historical footnote. It’s a powerful lesson in how scientific evidence, community action, and bureaucratic inertia collided in the fight against one of humanity’s most feared diseases.

The Medical Mystery and the “Vaccine Failure”

When Dr. John began his investigation, cases of “vaccine-failure polio” were virtually unknown in the West, where OPV had been a resounding success. But his research, and studies from Delhi and Bombay, confirmed a troubling reality: the OPV used in India had alarmingly low immunogenic efficacy. For reasons linked to India’s high prevalence of enteroviruses, poor sanitation, and other factors, the standard three-dose regimen simply wasn’t working for many children.

The nation faced a cruel dilemma. The injected polio vaccine (IPV) had a proven, excellent track record of eliminating polio in countries like the US and Finland. Yet, IPV was not licensed for production or use in India. OPV was available but underperforming in the Indian context. Caught between two tools, India’s health system initially failed to adequately deploy either.

The Unintended Crisis: A “Man-Made” Epidemic

Amid this confusion, a catastrophic policy error unfolded. In 1978, India launched the WHO-backed Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI). Due to supply issues with OPV, the program rolled out by administering DPT (diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus) and BCG vaccines first.

Health officials overlooked a critical piece of medical knowledge: in a country hyper-endemic for polio, the DPT injection could itself trigger poliomyelitis in some cases. By inoculating 29 million children with DPT over four years while only giving 4.4 million the protective OPV, the stage was set for disaster.

The result was what Dr. John and his colleagues termed the “world’s largest iatrogenic [doctor-induced] outbreak of poliomyelitis.” A nationwide epidemic erupted in 1981, peaking at over 38,000 reported cases—with the actual toll estimated to be nearly 200,000. The human cost was staggering, and the economic loss was calculated at a breathtaking Rs 450 billion.

The Community That Said “Enough”

Facing rising vaccine failure rates and governmental inaction on his proposals for a five-dose OPV strategy or the licensing of IPV, Dr. John turned to his own community. He devised a radical idea: “pulse polio” campaigns. The concept was to vaccinate every eligible child in a concentrated geographic area in a short, intense burst, thereby interrupting the virus’s chain of transmission.

The national government was not interested. So, Dr. John bypassed them.

In a pioneering act of local cooperation, he partnered with the Rotary Club of Vellore and the Vellore Municipality. They divided the town into zones, set up vaccination stations, and mobilized the entire community through cinema hall announcements, newspapers, and handbills. This was not a top-down government directive; it was a grassroots movement fueled by a shared desire for a safer future for children.

For four half-days, volunteers from the CMC and local health centres worked tirelessly. The outcome was a triumph: a remarkable 62% of children in the area received three doses of OPV. Vellore had proven that even without a national mandate, a coordinated community could drastically curb the virus.

The Ripple Effect of a Local Victory

The success of the 1981 Vellore pulse polio campaign was a proof of concept that echoed across the nation. It demonstrated the power of a simple, focused strategy and community mobilization. Years later, when India launched its colossal, nationwide Pulse Polio Immunization program in 1995, it stood on the shoulders of this local experiment.

The story of Vellore is a profound reminder that public health breakthroughs are rarely just about the science. They are about the tenacity of individuals like Dr. T. Jacob John who refuse to accept failure. They are about the willingness of local communities to take ownership of their well-being. And they are a cautionary tale about the very real human cost when policy lags behind evidence.

Ultimately, India’s hard-won status as a polio-free nation—and a global vaccine leader—was not achieved by accident. It was forged in places like Vellore, through perseverance, collaboration, and the unwavering belief that a better future was possible.

You must be logged in to post a comment.