The Crossroads of Care: Decoding India’s Elusive “Health for All” Promise

Despite its ambitious “Health for All” goal, India’s public health system remains critically constrained by chronic underfunding, with expenditure stubbornly below 2% of GDP, which exacerbates a complex dual burden of persistent infectious diseases like tuberculosis and a sharp rise in non-communicable diseases, all intensified by environmental factors like air pollution. Systemic failures—including a fragmented regulatory apparatus that fails to ensure pharmaceutical quality and the escalating crisis of antimicrobial resistance fueled by misuse and poor oversight—further undermine universal health coverage. Bridging these gaps requires a fundamental shift towards robust, decentralized primary healthcare, stringent environmental and drug regulations, and a sustained political commitment to reframe health not as a welfare cost but as an essential investment in national resilience and economic security.

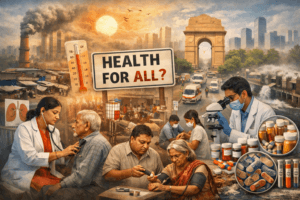

The Crossroads of Care: Decoding India’s Elusive “Health for All” Promise

The aspiration of “Health for All” in India stands at a critical juncture, caught between a legacy of underinvestment and the tidal wave of 21st-century health challenges. With a population nearing 1.5 billion, the nation’s public health system is not merely strained—it is being tested by a perfect storm of epidemiological transition, environmental crises, and systemic frailties. The goal, once a beacon of hope, now reveals a landscape marked by funding chasms, regulatory gaps, and a rising burden that threatens to outpace progress.

The Dual Disease Burden: A System Under Siege

India’s health profile is no longer defined by a single narrative. The country is grappling with a dual disease burden of historic proportions. On one front, infectious diseases like Tuberculosis (TB) remain deeply entrenched, with India accounting for a staggering proportion of global cases. The ambitious target to eliminate TB by 2025, while commendable, has collided with the realities of drug-resistant strains and inconsistent detection rates, despite advancements in indigenous diagnostic tools like TrueNat.

Simultaneously, a silent epidemic of **Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)**—diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers—is skyrocketing. Driven by urbanization, dietary shifts, and sedentary lifestyles, NCDs now account for over 60% of all deaths in India. This shift demands a fundamental reorientation of the healthcare system from a focus on acute, episodic care to one that manages chronic conditions over lifetimes—a transition for which it is woefully underprepared.

Compounding this is the insidious impact of climate change. Increasingly severe heatwaves, degrading air quality, and extreme weather events are not just environmental issues; they are potent health multipliers. Poor air quality alone has been shown to reduce average life expectancy by years, exacerbating respiratory and cardiovascular conditions and placing an unbearable load on already overstretched public facilities, particularly in North India.

The Chronic Ailment: Persistent Underfunding

At the heart of India’s healthcare conundrum lies a chronic issue: perennial underfunding. For decades, India’s public health expenditure has hovered around a meager 1.2-1.5% of its GDP, one of the lowest figures among peer nations. While the National Health Policy 2017 set a target of 2.5% by 2025, the current allocations—though nominally increased—fall short of what is required to build a resilient system for a population of this scale.

This funding gap has been exacerbated by the withdrawal of key international aid in areas like HIV/AIDS and reproductive health. The fiscal onus has shifted entirely to Union and State coffers, leading to stark inter-state disparities in capacity and access. The Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY), while a landmark step towards financial protection, primarily addresses secondary and tertiary care. The neglect of primary healthcare funding remains the system’s Achilles’ heel, undermining prevention and early intervention, which are crucial for managing both TB and NCDs.

The Twin Threats: Antimicrobial Resistance and Regulatory Frailty

Beyond the burden of disease, two systemic failures pose existential threats to public health security:

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR): India is often described as the epicenter of the global AMR crisis. Resistance rates for common pathogens are alarmingly higher than global averages. This is not a natural phenomenon but a man-made disaster fueled by:

- The rampant over-the-counter sale of antibiotics.

- Widespread self-medication and incomplete treatment courses.

- Poor infection control in hospitals.

- Environmental contamination from pharmaceutical effluent. A future where common infections become untreatable is not dystopian fiction; it is a looming reality if India’s National Action Plan on AMR is not implemented with unprecedented rigor.

- Pharmaceutical Quality & Regulatory Oversight: Recent tragedies, such as the deaths linked to contaminated cough syrups, have exposed a fractured regulatory landscape. India’s proud title of “Pharmacy of the World” is undermined when domestic quality control fails. These incidents point to deep-seated issues:

- Fragmented authority between central and state regulators.

- Inadequate testing infrastructure and manpower.

- Weak enforcement and accountability mechanisms. Ensuring drug safety is non-negotiable, both for domestic health security and for maintaining global trust in Indian pharmaceuticals.

The Road to Resilience: A Multi-Pronged Prescription

Achieving “Health for All” in this complex context requires moving beyond piecemeal solutions to a coherent, war-footing strategy.

- Prioritize Primary Health Care (PHC): The cornerstone of any resilient system is a robust PHC network. Substantial, sustained investment is needed to strengthen Sub-Centers and Primary Health Centers, making them the first and most accessible point of comprehensive care, including for NCD screening and management.

- Decentralize and Integrate: A one-size-fits-all approach is destined to fail. Health planning must be decentralized to the district level, allowing for tailored responses to local disease patterns and environmental challenges. Vertical disease-control programs (for TB, AIDS) need better integration with general health services to improve efficiency and patient experience.

- Environmental Health as Public Health: Air pollution control, heat action plans, and water security cannot remain solely within environmental ministries. They must be core, budgeted components of public health strategy, with clear inter-ministerial coordination.

- Foster a Culture of Rational Medicine: Combating AMR requires a societal shift. This demands strict enforcement of prescription-only antibiotic sales, massive public awareness campaigns, and the promotion of antimicrobial stewardship programs in every hospital.

- Overhaul the Regulatory Ecosystem: India needs a unified, empowered, and transparent national drug authority with adequate resources for inspection, testing, and swift punitive action. Quality must be the brand, not an afterthought.

- Innovative Financing: Exploring dedicated health cesses (e.g., on tobacco, sugary drinks, pollution), encouraging corporate social responsibility in health infrastructure, and outcome-based funding models can help bridge the resource gap.

Conclusion: A Question of Political Will

The path to “Health for All” in India is neither mysterious nor unattainable. The diagnoses are clear, and the prescriptions are well-known. The gap lies in execution, scale, and sustained political commitment. Health must be reframed not as a welfare expenditure, but as a fundamental driver of human capital, economic productivity, and national security. In the face of converging crises, the choice is between investing decisively in a system that can protect all citizens or managing the perpetual chaos of a system on the brink. The health of the nation, in every sense, depends on this choice.

You must be logged in to post a comment.