The Creeping Venom: How Climate Change is Reshaping India’s Snakebite Map

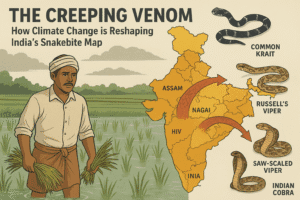

Rising global temperatures are redrawing the geographic distribution of India’s “Big Four” venomous snakes—the common krait, Russell’s viper, saw-scaled viper, and Indian cobra—pushing their habitats from traditional hotspots in states like Karnataka and Gujarat towards new human-dominated areas in northern and northeastern regions such as Assam, Manipur, and Rajasthan.

This climate-driven shift, combined with high socioeconomic vulnerability and often limited healthcare access in these areas, significantly increases the risk of snakebite incidents and fatalities. Experts emphasize that addressing this looming public health crisis requires a proactive “One Health” approach, integrating stronger healthcare systems with widespread community awareness, trained snake rescuers, and real-time monitoring to effectively mitigate the growing human-snake conflict and halve snakebite deaths by 2030.

The Creeping Venom: How Climate Change is Reshaping India’s Snakebite Map

Meta Description: Climate change isn’t just melting glaciers—it’s pushing India’s most venomous snakes into new territories, setting the stage for a hidden public health crisis in unprepared northern and northeastern states.

Introduction: A Looming Crisis in the Shadows

Imagine a farmer in Assam, bundling harvested rice, his mind on the monsoon clouds. For generations, the immediate dangers in his fields were familiar. Soon, they may include a threat his grandfather never knew: the saw-scaled viper, a snake whose range is steadily marching northward, driven by a changing climate. This isn’t a scene from a dystopian novel; it’s the future of public health in India, as forecast by a groundbreaking new study.

Recent research, a collaboration between Indian and South Korean scientists published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, delivers a stark warning: climate change is actively redrawing the geographical distribution of India’s “Big Four” venomous snakes. This silent migration is shifting snake populations towards human-dominated landscapes, turning snakebite from a perennial rural hazard into a escalating crisis poised to explode in new, unprepared regions. For a nation that already bears the grim title of the snakebite capital of the world, with 46,000 to 60,000 annual fatalities, this represents a profound and unanticipated challenge.

The “Big Four” on the Move: Understanding the Shift

The study focuses on the four species responsible for the vast majority of life-threatening envenomations in India:

- Common Krait (Bungarus caeruleus): Nocturnal and highly venomous, often found in homes and agricultural fields.

- Russell’s Viper (Daboia russelii): A major cause of snakebite deaths, frequently encountered in farmlands.

- Saw-scaled Viper (Echis carinatus): A small, irritable snake known for its potent haemotoxic venom.

- Indian Cobra (Naja naja): The iconic spectacled snake, thriving in a variety of habitats, including villages.

But why are they moving? Snakes are ectotherms; their body temperature and, by extension, their activity, digestion, and reproduction, are governed by their environment. As climate change alters temperature gradients and rainfall patterns, the “climatic envelope” that defines a species’ suitable habitat expands, contracts, or shifts.

“The ecosystem is what finally decides the distribution of snakes, prey, and what the prey depend on,” explains Dr. Jaideep Menon of the Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, who was not involved in the study but advocates for a One Health approach to snakebites. He points out that this isn’t just about the snakes themselves. If arid regions become greener, they may become more hospitable to Russell’s vipers and less so to saw-scaled vipers. The entire food chain is in flux, and snakes are simply following the trail.

The New Snakebite Hotspots: From Karnataka to Assam

The study’s modeling reveals a dramatic geographical pivot in risk. Currently, high-priority districts are concentrated in states like Karnataka (Chikkaballapura, Haveri) and Gujarat (Devbhumi Dwarka). These are traditional snakebite hotspots where the human-snake interface is long-established.

However, the future scenario paints a different picture. The models project a significant increase in snakebite risk across many northern and northeastern states, highlighting districts such as:

- Assam: Nagaon, Morigaon, Golaghat

- Manipur: Tengnoupal

- Rajasthan: Pratapgarh

This northward and northeastern shift means that communities with less historical experience and potentially lower awareness of these venomous snakes will soon be facing heightened exposure. The cultural knowledge of “what snake is that” and “what to do” is not innate; it is learned through generations of coexistence—a learning curve these regions may be forced to climb rapidly, and tragically.

More Than Just Snakes: The Triple-Threat Risk Index

What makes this research uniquely insightful is that it doesn’t stop at predicting snake locations. It calculates a “Risk Index” by weaving together three critical threads:

- Ecological Overlap: How much will future snake habitat overlap with croplands and human settlements? This is the point of contact, the literal ground zero for conflict.

- Socioeconomic Vulnerability: How resilient is a community? Factors like poverty, reliance on agriculture, literacy rates, and social structure determine a community’s ability to prevent bites and cope with the aftermath. A bite can plunge a family into debt due to medical costs and lost wages.

- Healthcare Access and Capacity: How quickly can a victim get effective treatment? This includes the proximity of a primary health center, the availability of antivenom, and the presence of trained medical staff who can administer it correctly.

As the study’s lead author, Shantanu Kundu, clarifies, the initial motivation was the staggering number of Indian snakebite cases. “We found that most studies focused directly on snakebite incidents, whereas our primary area of work, i.e., spatial ecology, was scarcely represented,” he told Mongabay India.

This holistic view reveals that a snakebite is not merely a random encounter with wildlife; it is a “poverty-related neglected tropical disease,” a perfect storm where ecological, climatic, and social vulnerabilities collide.

A Global Pattern and India’s Path Forward

India’s situation is part of a wider, alarming trend. The World Health Organization (WHO) and a 2024 report in The Lancet Planetary Health have both flagged that climate change is likely to increase snakebite risks in tropical countries, particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa. Nations like Uganda, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Thailand are facing similar forecasts.

So, what can be done to halt this creeping crisis? The solution requires a multi-pronged, “One Health” strategy that recognizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health.

- Fortify the Healthcare Frontlines: The National Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Snakebite Envenoming (NAP-SE), launched in March 2024 with a goal to halve deaths by 2030, is a crucial step. However, experts like Dr. Menon warn that “old pitfalls” persist. There’s an urgent need to:

- Pre-emptively stock antivenom in emerging hotspot districts based on predictive modeling.

- Train primary healthcare doctors to overcome the fear of adverse reactions and administer antivenom confidently.

- Strengthen the cold chain to ensure antivenom, a biological product, remains effective.

- Empower Communities with Knowledge, Not Fear: “Awareness” must move beyond posters. It means:

- Dispelling deadly myths about first aid (e.g., no tourniquets, no cutting the wound).

- Teaching identification of the Big Four to reduce panic and inform treatment.

- Training community snake rescuers who can respond safely and swiftly. Kundu strongly cautions that this “must not treat the activity as public display or entertainment,” which can be dangerous and send the wrong message.

- Implement Real-Time Intelligence Systems: Dr. Menon’s recommendation for real-time dashboards tracking snake sightings, rescues, and bites would be a game-changer. This live data would allow for dynamic resource allocation and create an early-warning system for communities.

Conclusion: A Test of Resilience

The shifting ranges of India’s venomous snakes are a potent symbol of the tangible, human costs of climate change. It is a threat that slithers into homes and farms, disproportionately affecting the most vulnerable. The challenge is no longer just about conserving snakes or treating bites in isolation; it is about building systemic resilience.

The coming decades will test our ability to adapt not only our infrastructure and healthcare but also our knowledge. By marrying cutting-edge ecological modeling with robust public health action and deep community engagement, India can transform this forecasted crisis into a story of proactive human ingenuity. The snakes are moving. Our response must be even faster.

You must be logged in to post a comment.