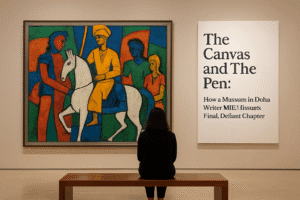

The Canvas and The Pen: How a Museum in Doha Writes M.F. Husain’s Final, Defiant Chapter

The Lawh Wa Qalam: M.F. Husain Museum in Doha, which opened in November 2025, represents the profound posthumous realization of the artist’s final vision, a promise kept by his patron and friend, Sheikha Moza bint Nasser of Qatar.

Fourteen years after his death and exile from India, this institution—born from Husain’s own 2008 architectural sketch—houses over 150 works that trace his evolution from iconic Indian modernist to an artist deeply engaged with Arab civilization during his last years. More than a static gallery, the museum serves as a dynamic cultural bridge and a sanctuary for his legacy, featuring his monumental kinetic installation Seeroo fi al Ardh and actively fostering East-East dialogue, thereby transforming a narrative of exile into one of enduring, cross-cultural artistic synthesis.

The Canvas and The Pen: How a Museum in Doha Writes M.F. Husain’s Final, Defiant Chapter

In the heart of Doha’s Education City, a structure clad in brilliant blue mosaic rises from the desert, its façade inscribed with Arabic calligraphy that reads Lawh Wa Qalam—The Tablet and The Pen . This is not merely a new museum; it is the materialisation of a 2008 sketch, the keeping of a royal promise, and the profound posthumous homecoming for Maqbool Fida Husain, one of modern art’s most celebrated and contentious figures . Opened in November 2025, the Lawh Wa Qalam: M.F. Husain Museum represents what many are calling the “unthinkable finale” for the artist: a monumental legacy project realised not in his native India, but in the Qatari capital that offered him sanctuary . This institution transcends the conventional role of a museum; it is a bridge between civilisations, a sanctuary for an exiled legacy, and a powerful statement on artistic freedom in the 21st century.

From Sketch to Sanctuary: The Architecture of a Fulfilled Promise

The museum’s very existence is a testament to enduring patronage and personal loyalty. The vision was born from a humble proposal Husain made to his friend and patron, Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, Chairperson of the Qatar Foundation . In a letter, he outlined his dream: a museum to house his life’s work, designed by himself . Fourteen years after his death in 2011, Sheikha Moza delivered on that promise, spearheading the project to completion . The architectural challenge fell to Delhi-based architect Martand Khosla, who began not with blueprints, but with Husain’s own coloured sketch of a “blue building” .

Khosla’s task was to translate symbolic vision into functional space. The original sketch, operating on “literal, symbolic and metaphorical” levels, provided the conceptual DNA . The iconic blue-tiled façade and the inscribed name became the defining external elements . Internally, the architecture avoids a linear, restrictive path. Instead, it encourages a nomadic journey of discovery, mirroring Husain’s own peripatetic life . Spaces flow into one another, offering elevated views and points for reflection. A central tower acts as a “cinematic periscope,” extending sightlines across the region and echoing the cross-cultural exchanges that defined the artist’s career . The building, therefore, becomes an active participant in the narrative—not a silent container, but a spatial experience that embodies Husain’s restless, inquisitive spirit .

A Collection in Two Acts: India, Exile, and Arab Renaissance

Housing over 150 works, the museum’s collection is strategically curated to tell the dual story of Husain’s artistic identity . The first level serves as an anchor to his roots, showcasing works from his decades in India. This includes not only paintings but poignant personal artifacts: his last used paint palette, brushes, a paint-splattered kurta, and his Indian passport . The passport is a silent, powerful relic of his painful departure, a symbol of the “heightened stress… amidst protests and death threats” that eventually led him to leave India in 2006 .

The second act of the collection, and arguably its heart, presents the art of his final decade, created after he accepted Qatari citizenship in 2010 . This section highlights a profound artistic evolution, featuring works from his ambitious, unfinished series of 99 paintings on Arab civilisation, commissioned by Sheikha Moza . Here, Husain’s iconic horses charge into new historical landscapes. In The Battle of Badr (2008), they depict a pivotal Islamic victory . Zuljanah (2007) is a portrait of the horse of Imam Hussain, connecting to the history of Karbala . These works represent more than a new subject matter; they signify Husain’s deep engagement with the heritage of his adopted home, a dialogue between his Indian modernist vocabulary and Arab historical motifs . As Kholoud Al-Ali of Qatar Foundation notes, his art began to carry “many voices at once – Indian, Arab, global – all meeting on the same canvas” .

The Climactic Installation: Seeroo fi al Ardh (Walk in the Land)

The museum’s crescendo is Husain’s final masterpiece, the kinetic installation Seeroo fi al Ardh (Walk in the Land), conceptualised in 2009 . Housed in a dedicated gallery, this work is the full expression of his multidisciplinary genius and serves as his artistic last will and testament. The installation is a breathtaking ensemble: a red-mosaic mural of running horses forms a backdrop, while sculptural horses, hand-blown in Murano glass, gallop around a stage . In a dynamic choreography, these horses give way to vintage cars that rise on hydraulic lifts .

Husain left detailed instructions for every aspect—”every movement, every light mood, every musical note” . He described it as “a performance of dancing horses in crystal glass set to the tune of a traditional song of horsemanship, chivalry and strength” . This work, conceived during a period of personal crisis amid controversies in India, transcends its components. It is a jubilant, kinetic poem about movement, progress, and the synthesis of tradition (the horse) with modernity (the sports car) . It encapsulates his lifelong fascination with motion and positions him not just as a painter, but as a visionary of total art.

Beyond the Canvas: The Museum as Cultural Bridge and Educational Hub

The Lawh Wa Qalam Museum’s significance extends far beyond preserving a single artist’s oeuvre. Its location within Qatar Foundation’s Education City is deliberate, reflecting a core philosophy that art is integral to learning and civic life . The museum is conceived as a dynamic hub, not a static mausoleum. It plans to host rotating displays, workshops, screenings, and university collaborations, actively fostering dialogue . Curator Noof Mohamed emphasizes that the goal is to create “a space that stays alive,” mirroring Husain’s own movement between mediums .

Furthermore, the institution consciously positions itself as a bridge for “East-East” conversations, challenging the traditional Western-centric narrative of modernism . By placing a titan of Indian modernism in direct conversation with Arab history and within a Qatari educational ecosystem, the museum constructs a new cultural axis. It asserts that modernity was a global conversation, and that Husain’s work, with its synthesis of Indian, Arab, and Western influences, is a prime testament to that . As Sahar Zaman, a journalist who knew Husain, writes, it sits “in the middle of the East and the West” and aims to “bridge two parts of the world and help create a new dialogue” .

Conclusion: The Unthinkable Finale as a New Beginning

The opening of the Lawh Wa Qalam Museum in 2025 indeed marks an unthinkable finale. It is the culmination of a journey that saw Husain rise from a Bombay cinema billboard painter to a global modernist, face exile from his homeland, and find both peace and a new creative zenith in Qatar . This museum is his final, defiant act of authorship—”the author of the final chapter of his own story” .

Yet, in its dynamism, this finale feels less like an end and more like a new genesis. The museum does not entomb Husain’s legacy; it liberates and contextualizes it on a global stage. It transforms a narrative of conflict and exile into one of reconciliation, cross-cultural synthesis, and enduring creative force. By fulfilling a promise to a friend, Qatar has not only honoured an artist but has also built a powerful monument to the idea that art can transcend borders, heal divisions, and write its own enduring future. The tablet and the pen are now in the hands of the visitors, scholars, and artists who will walk through its blue doors, ensuring that M.F. Husain’s restless, nomadic spirit continues its journey.

You must be logged in to post a comment.