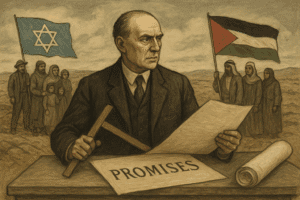

The Architect of a Conflict: How Britain’s Contradictory Promises Forged the Israel-Palestine Tragedy

Britain’s role in the history of Israel and Palestine was that of a central and controversial architect, whose contradictory promises during and after the First World War laid the foundation for the enduring conflict. In a series of incompatible commitments, Britain pledged support for an independent Arab state to secure an Arab revolt against the Ottomans, secretly agreed with France to divide the region, and then issued the Balfour Declaration, promising a “national home for the Jewish people” in the same land.

This contradiction was embedded in its League of Nations Mandate, leading to three decades of impossible governance that culminated in a brutal suppression of Arab dissent and a eventual decision to partition the territory. Weakened after World War II, Britain abruptly abandoned its Mandate in 1948, handing the problem to the UN and withdrawing without ensuring a peaceful transition, which directly precipitated a war, the establishment of Israel, and the displacement (Nakba) of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, a legacy for which Britain bears a unique historical responsibility.

The Architect of a Conflict: How Britain’s Contradictory Promises Forged the Israel-Palestine Tragedy

The announcement by UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy at the United Nations in July 2025, recognising a Palestinian state, was laden with historical irony. He spoke of feeling “the hand of history on his shoulders,” a sentiment that is profoundly apt. For no other nation bears as direct and weighty a responsibility for the very contours of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as Great Britain. From the sunlit chambers of imperial power to the messy, violent withdrawal from a land it could no longer control, Britain’s actions between 1915 and 1948 did not merely influence the dispute; they designed its blueprint.

The story is not one of simple villainy but of imperial hubris, wartime expediency, and a staggering failure to anticipate the consequences of making three mutually exclusive promises to three different peoples. To understand the modern impasse is to journey back to the crucible of the early 20th century, where Britain, as the dominant power, laid a foundation of sand upon which a century of conflict would be built.

The Tangled Web: Three Promises for One Land

As the First World War raged, the British Empire faced the formidable Ottoman Empire, which controlled the vast territories of the Middle East. Desperate for allies and advantage, London embarked on a strategy of strategic promise-making that would become a textbook example of diplomatic catastrophe.

- The Promise to the Arabs (1915-1916): The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence In a series of letters with Sharif Hussein of Mecca, the custodian of Islam’s holiest sites, British High Commissioner Sir Henry McMahon explicitly encouraged an Arab revolt against the Ottomans. The understanding, from the Arab perspective, was clear: in exchange for their uprising, Britain would support the creation of a single, independent Arab state spanning the liberated Ottoman territories, including the region of Palestine. This promise ignited the Arab Revolt of 1916, a key factor in the Ottoman defeat, led famously by T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”).

- The Secret Promise to the French (1916): The Sykes-Picot Agreement Simultaneously, and in utter secrecy, British and French diplomats Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot were carving up the very same land. The Sykes-Picot agreement was a classic imperialist bargain, drawing straight lines on a map to create spheres of influence. Palestine was designated for an ambiguous “international administration,” a plan that paid no heed to Arab aspirations for independence. The revelation of this agreement years later was seen by Arabs as the ultimate betrayal, a stark lesson in Western duplicity.

- The Promise to the Jewish People (1917): The Balfour Declaration The most famous and fateful of these commitments came in November 1917. In a brief letter to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour declared that His Majesty’s Government “view[ed] with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” The caveat—”it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”—proved tragically insufficient.

The motivation was complex: a mix of genuine (if somewhat romanticised) sympathy for Zionism, a desire to secure Jewish support for the war effort in the US and Russia, and a calculation that a future Jewish entity in Palestine would be a reliable British client, protecting the strategic approaches to the Suez Canal.

Balfour’s own words, written in 1919, reveal the profound colonial mindset that underpinned the declaration: “Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes of far greater import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.” In this single sentence, the political rights of the indigenous Arab majority were dismissed as mere “desires and prejudices,” unworthy of standing in the way of a grander European project.

The Impossible Mandate: Governing a Contradiction

In 1922, the League of Nations formalised British control over Palestine through a “mandate.” Crucially, the text of the Balfour Declaration was embedded within it, making Britain legally responsible for facilitating Jewish immigration while also protecting the rights of the Arab population. This was an impossible mandate in the literal sense. The British were tasked with building a “national home” for one people in a territory where another people constituted over 90% of the population and fiercely opposed the project.

As Jewish immigration, driven by Zionism and later by the rise of Nazism in Europe, increased throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Palestinian anxiety turned to anger. This culminated in the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939, a widespread uprising against British rule and Zionist settlement. The British response was brutally efficient, crushing the revolt and decimating the Palestinian political and military leadership—a blow from which the community would not recover before the crucial events of 1948.

The 1937 Peel Commission, acknowledging the unsustainable situation, proposed for the first time the concept of partition: dividing the land into separate Jewish and Arab states. The plan, which allotted the more fertile coastal areas to the Jewish state and called for the forced transfer of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, was rejected by Arabs but established partition as the “solution” of choice for the international community.

By 1939, with war looming in Europe, Britain attempted a reversal. The 1939 White Paper, seeking to appease Arab states vital to wartime interests, severely restricted Jewish immigration and proposed a single, binational state with an Arab majority within ten years. To Zionists, this was a profound betrayal, coming at the very moment European Jews were desperate for refuge. It irrevocably turned the Zionist movement against Britain, leading to a campaign of guerrilla warfare and terrorism.

The Abdication: Washing Their Hands of Palestine

By 1947, a war-weakened and bankrupt Britain had had enough. Faced with escalating violence from both Jewish militias and Arab forces, Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin declared the Mandate unworkable and handed the problem to the newly formed United Nations. This was not a graceful exit but an abdication of responsibility. Britain largely refused to cooperate with the UN committee and, after the UN passed Resolution 181 in November 1947 recommending a new partition plan, announced it would simply leave by May 1948, doing little to implement the plan or maintain order.

The result was a vacuum, and into that vacuum poured war. When Israel declared independence in May 1948, neighbouring Arab states intervened. The ensuing conflict saw the new State of Israel consolidate its territory and expand beyond the UN borders. The most catastrophic consequence for the Palestinians was the Nakba (“catastrophe”): the displacement of approximately 750,000 Palestinians from their homes, creating a refugee problem that remains at the heart of the conflict today.

Britain, the supposed overseer, largely “washed its hands,” leaving the two sides to fight it out. As the article notes, the United States then stepped into the power vacuum, gradually becoming Israel’s primary patron, while Britain retreated into a quieter, often ambivalent, diplomatic role.

The Long Shadow of History

David Lammy’s 2025 announcement of recognition is, in a way, a late and symbolic attempt to close a circle that Britain opened over a century ago. It is an admission that the promise of self-determination made implicitly to the Palestinians in 1915 was broken, and that the political reality on the ground has made a two-state solution, first proposed by Britain in 1937, the only viable path forward.

The legacy of the British Mandate is a stark lesson in the perils of imperial diplomacy. It demonstrates how the strategic interests of a great power, executed through contradictory promises and a failure to understand the national aspirations of local populations, can plant the seeds of intractable conflict. The borders, the grievances, the refugee crisis, and the very competing claims to national identity that define the Israel-Palestine issue today were all set in motion during those three decisive decades of British rule. The hand of history on the foreign secretary’s shoulders is indeed a heavy one, for it is the weight of a legacy his country created.

You must be logged in to post a comment.