The Aadhaar Paradox: When India’s Digital Proof of Life Fails as Proof of Citizenship

India’s Aadhaar system, originally launched as a universal proof of identity to streamline welfare, has paradoxically become a tool for excluding citizens from their fundamental rights, as exemplified by the 2025 Election Commission’s decision in Bihar to disqualify Aadhaar as sufficient proof of citizenship for voter registration.

This move, echoing a similar crisis in Assam, exposes the fragility of a digital identity system riddled with authentication failures and a deep digital divide, which disproportionately disenfranchises the poor, migrants, and marginalized groups. By creating a system where citizenship is constantly reverified by flawed algorithms and hard-to-obtain documents, India is shifting from territorial borders to digital borders, undermining the very constitutional promise of universal suffrage and risking the transformation of citizenship from a right into a conditional privilege granted by the state.

The Aadhaar Paradox: When India’s Digital Proof of Life Fails as Proof of Citizenship

In the mid-1990s, a political drama unfolded in Bihar that would foreshadow a much larger crisis three decades later. Frustrated by the uncompromising rigor of India’s Chief Election Commissioner, T.N. Seshan, Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav famously quipped, “Yee Seshanwa chunaav karwa raha hai ki kumbh?” (“Is this Seshan conducting an election or a pilgrimage?”).

Seshan’s mission—to cleanse elections of malpractice by insisting on verifiable identity, like photo IDs—marked a pivotal turn. It signaled India’s nascent journey toward tying democratic participation to documentary proof. This journey would eventually lead to Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric ID system. But today, in that very same state of Bihar, Aadhaar’s promise is unraveling, exposing a fundamental contradiction at the heart of India’s digital citizenship project.

From Seshan’s ID to Aadhaar’s Algorithm: The Evolution of Documentary Citizenship

T.N. Seshan’s use of Article 324 of the Indian Constitution transformed the Election Commission from a passive body into a powerful arbiter of electoral integrity. His legacy was the establishment of a simple principle: to vote, you must prove you are who you say you are. The Voter ID card became a tangible symbol of this contract between the citizen and the state.

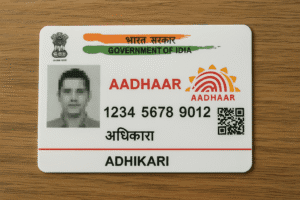

Aadhaar, launched in 2009, took this principle and scaled it to a breathtaking degree. Conceived to solve a basic problem—the lack of formal identification for nearly 400 million Indians, mostly the poor—it aimed to create a unique, irrefutable identity based on biometrics (fingerprints and iris scans). Its success in enrollment is undeniable; today, over 94% of India’s population possesses the twelve-digit number. It evolved from a tool for streamlining welfare to the de facto standard for proving identity, used for everything from opening bank accounts to filing taxes. In practice, it became the most widely accepted proof of residence and, by extension, an informal proof of citizenship.

This is where the paradox begins. Aadhaar was explicitly designed as a proof of identity, not a proof of citizenship. The distinction, once academic, has now become a legal and social fault line.

The Bihar Crucible: When Digital Identity is Suddenly Not Enough

In 2025, the Election Commission’s decision during the Bihar Special Intensive Revision (SIR) exercise sent shockwaves through the political and civil society landscape. The Commission declared that Aadhaar, along with the Voter ID card itself, would no longer be sufficient to prove citizenship for voter registration. The reason cited: susceptibility to falsification.

This move is a profound rupture. For years, the state has incentivized, and often mandated, linking Aadhaar to everything from phone numbers to pension schemes, creating a public perception of its infallibility and centrality to legal personhood. Now, the very authority that once championed documentary proof has invalidated the most ubiquitous document of all.

The immediate effect is a bureaucratic trap for the most vulnerable. The SIR exercise, aimed at reviewing ‘eligible’ citizens, now requires documents that are far harder to obtain than Aadhaar—such as a passport or birth certificate. This disproportionately impacts migrant workers, landless laborers, the elderly, and women, who are least likely to possess such paperwork. The timing and procedural fairness of this shift have been widely criticized, with the Supreme Court of India and civil society groups like the Association for Democratic Rights raising alarms. The fundamental risk is the wrongful exclusion of eligible citizens, not because they are not Indian, but because they cannot navigate the newly raised documentary barrier.

The question posed by the author is chillingly apt: “When a proof of existence is suspended, where does a citizen stand?” The answer, in Bihar, seems to be in a liminal space where their belonging is suddenly conditional.

The Assam Precedent: Aadhaar as a Tool of Exclusion

Bihar is not an isolated case; it echoes a more protracted crisis in Assam. There, Aadhaar has been strategically linked to the National Register of Citizens (NRC), a controversial exercise intended to identify “illegal immigrants.” The result is a Kafkaesque situation. In April 2025, nearly a million individuals in Assam received Aadhaar cards after a five-year delay. Meanwhile, 1.8 million others, excluded from the NRC, remain in a legal limbo—unable to get Aadhaar, and thus stripped of access to basic services and legal recognition.

In Assam, Aadhaar has morphed from a neutral identifier into the ultimate gatekeeper. Possessing it signifies validation by the state; its absence is a scarlet letter of questionable citizenship. The Bihar decision, while different in execution, follows the same logic: Aadhaar is becoming the informal guard against, rather than for, citizenship.

The Flawed Foundation: Aadhaar’s Inherent Inequalities

To understand why this is so dangerous, one must look at Aadhaar’s own troubled architecture. The system is far from the seamless, equitable solution it is often portrayed to be. Its rollout has been riddled with issues that disproportionately affect the margins:

- Authentication Failures: There are harrowing accounts of “hunger-deaths” when ration supplies were denied due to fingerprint authentication failures—a common problem for elderly individuals or those whose fingerprints are worn down by a lifetime of physical labor.

- The Digital Divide: The process of enrolling, updating, or correcting biometric data is heavily reliant on digital literacy and physical access to centers. With only 24% of rural India having meaningful internet access, this creates an insurmountable barrier for many.

- Structural Bias: The system inherently disadvantages historically oppressed groups like Adivasis (indigenous tribal groups) and Dalits, who often face greater hurdles in accessing bureaucratic resources. The plea of a widow whose pension was abruptly stopped—“The computer has killed me. I request you to please make me alive again.”—is a stark metaphor for the system’s brutal indifference.

When a system with these inherent flaws is then used as a gatekeeper for citizenship itself, it doesn’t just risk exclusion; it systematizes it.

Beyond the Glitch: The Rise of Algorithmic Borders

The crisis in Bihar and Assam signals a profound shift in the nature of citizenship itself. Historian Benedict Anderson famously described nations as “Imagined Communities,” bound by a shared sense of identity. Today, that imagination is being codified into algorithms.

We are witnessing a move from territorial borders to digital borders. Citizenship is no longer a right granted by birth on a territory but a status that must be constantly re-verified and authenticated through data points. This creates overlapping layers of what can be called algorithmic bordering, where a citizen’s legitimacy is never permanently granted.

This system does not just criminalize individuals; it criminalizes a way of life—being poor, being mobile (like migrant workers), and being undocumented in the specific ways the system demands. It internalizes the border, placing it between the citizen and their phone, their bank, and their ballot box.

As scholar Anupama Roy has argued, the “liminal” status of citizenship has a long and scarred legacy in South Asia, dating back to the Partition of 1947. Writer Urvashi Butalia’s work reminds us how that event made citizens and non-citizens overnight, a trauma that continues to haunt the present. The danger today is that technology is allowing this liminal status to be manufactured at scale, with the cold efficiency of an algorithm.

Toward a More Humane Verification: A Path Forward

The solution is not to simply reinstate Aadhaar as the sole arbiter of citizenship, nor is it to discard it outright. The solution lies in building a more equitable and humane system for verifying citizenship. This requires:

- A Multi-Document Framework: Accepting a wider range of documents, including those that recognize long-standing residence rather than just formal bureaucracy, such as property records, old utility bills, or even panchayat (local council) attestations.

- Procedural Safeguards: Ensuring that the burden of proof does not fall entirely on the individual. The state must take a proactive role in establishing citizenship, rather than presuming exclusion.

- Sensitivity to Context: Actively accounting for barriers of poverty, disability, and the digital divide. Verification processes must be accessible to all, not just the literate and well-resourced.

Conclusion: The Soul of a Democracy

When India votes, it is an exercise of immense hope and faith. But when the ritual of voting is preceded by the ritual of technological verification that millions cannot pass, the soul of that democracy is dimmed. The crisis in Bihar is a canary in the coal mine, a warning of what happens when citizenship becomes a function of data integrity rather than constitutional right. The dream of a digital India must not come at the cost of excluding the very people it was meant to empower. Otherwise, the imagined community risks becoming a ghost town, populated only by those with the right papers in an increasingly paperless world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.