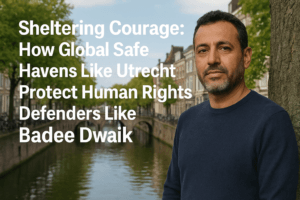

Sheltering Courage: How Global Safe Havens Like Utrecht Protect Human Rights Defenders Like Badee Dwaik

The Shelter City Utrecht program, run by Peace Brigades International and Justice & Peace, provides a three-month safe haven for at-risk human rights defenders to rest, build skills, and network. Its current guest is Palestinian defender Badee Dwaik, a co-founder of Human Rights Defenders in Palestine who documents abuses and organizes peaceful campaigns in Hebron, where he was recently detained and abused by Israeli soldiers. His respite in Utrecht highlights a global crisis, as organizations report dozens of Palestinian defenders were killed in recent years, underscoring the urgent need for international protection mechanisms that allow activists like Dwaik to recover and safely continue their vital, non-violent work for justice.

Sheltering Courage: How Global Safe Havens Like Utrecht Protect Human Rights Defenders Like Badee Dwaik

The peaceful streets of Utrecht offer a stark contrast to the tension of Hebron’s Old City. For Palestinian human rights defender Badee Dwaik, this Dutch city is more than a picturesque European destination; it is a temporary safe haven, a place to breathe, recover, and prepare to continue a dangerous but vital fight. His three-month stay, made possible by the Shelter City Utrecht project, underscores a growing global response to an urgent crisis: the escalating threats against individuals who stand up for human rights in some of the world’s most challenging environments.

A Timeline of Refuge and Resilience

The Shelter City program and Badee Dwaik’s journey highlight a long-term commitment to protecting human rights defenders.

More Than a Hiding Place: The Shelter City Model

Established in 2012 by the Dutch NGO Justice & Peace, Shelter City was founded on a powerful yet simple premise: to provide temporary safe spaces for human rights defenders under threat. The program’s coordinators recognized that defenders needed more than just physical safety; they needed an opportunity to rest, learn, and connect. What began in the Netherlands has since grown into a global movement, with 22 cities across multiple continents offering similar refuge.

Shelter City Utrecht, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, has been a cornerstone of this initiative. The city itself was declared “the first human rights city of the Netherlands” in 2012, making it a fitting home for the project. The program operates on a collaborative model, implemented locally by Peace Brigades International in partnership with the Utrecht municipality.

The support offered is intentionally holistic, designed to address the multifaceted needs of a defender who has been working under extreme pressure. This model is built on three core pillars:

| Pillar of Support | Description & Activities |

| Rest & Re-energize | A safe environment to recover from threats and trauma. Includes access to psychological and physiological support. |

| Tailored Skill Development | Training in digital security, advocacy, public speaking, and English language. Aims to build resilience and effectiveness. |

| Networking & Awareness | Opportunities to connect with NGOs, politicians, journalists, and the public to build alliances and spotlight human rights issues. |

The selection process is rigorous. Defenders must demonstrate a commitment to non-violent work and prove they are under genuine threat. Crucially, they must be willing and able to return to their home country after three months to continue their work, as the program’s goal is to reinforce local actions, not to facilitate permanent emigration.

The Defender: Badee Dwaik’s Work in Hebron

Badee Dwaik’s story exemplifies the exact dangers the Shelter City program seeks to mitigate. For over twenty years, the 52-year-old has been a prominent voice for justice in Hebron (Al-Khalil), a West Bank city known for its particularly tense environment of military checkpoints and settlements.

His work is multifaceted. He is a leading member and co-founder of “Human Rights Defenders in Palestine,” a grassroots organization that documents raids, attacks, and abuses by soldiers and settlers, sharing this evidence with a global audience. His mission extends beyond documentation; he actively organizes peaceful campaigns for the protection of fellow defenders, calls for an end to the occupation, and trains others in safety and protection strategies, especially in the volatile Hebron governorate.

This work comes at a high personal cost. In June 2025, Israeli soldiers detained Dwaik at the entrance to Hebron’s Old City. He was searched, abused, forced to the ground, and had the contents of his phone deleted after attempting to film the soldiers’ actions. This incident is not an isolated one but part of a pattern of intimidation.

Dwaik’s objectives for his stay in Utrecht reflect both his immediate needs and his long-term vision. He seeks well-deserved rest in an environment free from constant fear. Furthermore, he aims to use the platform to “spread awareness regarding the situation in Palestine” by speaking publicly, connecting with other activists, and engaging with politicians at municipal, national, and European levels. His goal is to spark institutional discussion and promote concrete action for the Palestinian cause.

A Global Crisis and the Call for Solidarity

Dwaik’s perilous situation is, tragically, far from unique. The organization Front Line Defenders has documented the killing of at least 31 Palestinian human rights defenders in 2023 and 2024 alone, acknowledging that the true number is likely higher due to the extreme difficulty of documentation in conflict zones. Those targeted include not just activists like Dwaik but also journalists, medical workers, and humanitarian aid staff.

This crisis forms the urgent backdrop against which programs like Shelter City operate. The program has supported over 699 defenders from around the world, including individuals from Kenya, Mexico, Thailand, and Ukraine, working on issues from LGBTIQ+ rights to environmental justice. For example, Olha, a 23-year-old Ukrainian anti-corruption activist, joined the program alongside Dwaik, seeking a space to recover and strengthen her skills for the fight against corruption in her home country.

The protection of these defenders is increasingly framed as a matter of international responsibility. The article from PBI-Canada, which originally covered Dwaik’s story, ties his plight to a broader political call for an arms embargo, citing UN experts who warn that continued material support to parties engaged in serious international crimes risks complicity in those crimes. This connects the micro-level act of sheltering one individual to the macro-level policies of governments and the global arms trade.

The Road Ahead: Resilience and Return

The ultimate success of the Shelter City model is measured by what happens when defenders go home. The program is designed as a resilience-building respite, not an escape route. Most participants return to their countries with new skills, expanded networks, and renewed energy to continue their work.

For defenders like Badee Dwaik, returning to Hebron means stepping back into the fray. The threats will remain, but he will carry with him the solidarity witnessed in Utrecht, the skills acquired, and the knowledge that a global network of allies is watching. His poetry, recited at the ten-year anniversary celebration, is a testament to the power of voice—a voice that Shelter City helped protect and amplify.

In a world where civil society space is shrinking, initiatives like Shelter City offer more than just temporary shelter. They enact a powerful form of practical solidarity, affirming that the defense of human rights is a global responsibility. They provide a lifeline to those on the frontlines, ensuring that courage is not met with silence but with sustained and meaningful support.

You must be logged in to post a comment.