Seeding Illusions: Why India’s Desperate Attempt to Force Rain Failed to Wash Away Its Pollution Crisis

India’s controversial attempt to use cloud seeding to combat Delhi’s severe air pollution failed because the fundamental atmospheric conditions for the technique were absent; despite the government’s efforts to induce rain by dispersing silver iodide into the atmosphere, scientists concluded that the skies were too dry and stagnant, with major weather systems pulling moisture away from the region, making the operation futile.

While officials suggested a slight improvement in air quality resulted, researchers attributed any temporary clearing solely to a natural shift in wind patterns, underscoring that the failed experiment served as a costly distraction from addressing the root causes of the smog—such as agricultural burning, vehicle emissions, and industrial pollution—which require sustained, systemic solutions rather than technological quick fixes.

Seeding Illusions: Why India’s Desperate Attempt to Force Rain Failed to Wash Away Its Pollution Crisis

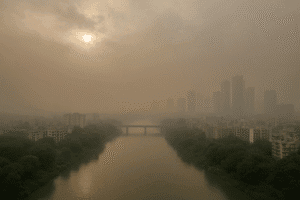

The scene in Delhi in late October is now a grimly familiar annual ritual. A thick, soupy smog, visible from space, descends upon the megacity. Eyes sting, throats rasp, and the air takes on a palpable, acrid taste. The world’s most polluted capital becomes a vast, uncontrolled experiment in public health, with pollution levels routinely hitting 20 times the World Health Organization’s safe limits. This year, however, the government promised a radical new weapon in this losing battle: the power to command the clouds.

The plan was cloud seeding—a controversial, decades-old technique where aircraft inject chemical nuclei like silver iodide or salt into promising clouds, aiming to coax out rain that would, in theory, scrub the atmosphere clean. But when the Indian government, in collaboration with IIT Kanpur, executed its trial on October 28th, the results were a resounding non-event. The skies did not open. The rain did not fall. And the subsequent, fleeting dip in pollution was attributed by independent scientists not to human intervention, but to the ancient, unpredictable whims of the weather itself.

This failure is more than a simple botched experiment; it’s a parable about the perilous allure of technological quick fixes when confronting deep-rooted, systemic environmental problems.

The Science of Forcing Rain from a Reluctant Sky

To understand why the experiment failed, one must first understand the delicate prerequisites of cloud seeding. It is not, as the name might suggest, a matter of creating clouds from nothing. Think of it less as creation and more as persuasion.

“Cloud seeding can only enhance rainfall if there are already moist, convective clouds with sufficient liquid water. It’s like providing a scaffold for a building; you still need the bricks and mortar,” explains Dr. Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology in Pune. “The seeding particles act as nuclei around which cloud droplets can coalesce, growing heavy enough to fall as rain.”

The critical missing ingredient over Delhi was atmospheric moisture. At the precise time the aircraft took to the skies, two major weather systems—a depression in the Arabian Sea and a cyclone in the Bay of Bengal—were acting like giant atmospheric vacuums, pulling all available moisture away from the northern plains. The skies over Delhi were not just clear; they were parched.

“In dry or stagnant air, there’s simply nothing to seed,” Dr. Koll states bluntly. “You cannot squeeze water from a stone, and you cannot seed a cloud that isn’t there.”

This leads to an uncomfortable question: why did the experiment proceed under such demonstrably unsuitable conditions? The decision hints at the immense political pressure to be seen acting decisively against the pollution crisis. When the public health emergency is televised and breathable air becomes a luxury, the allure of a sci-fi solution, however improbable, can override scientific caution.

The Mirage of Success and the Role of the Wind

In the aftermath, a curious narrative emerged. Officials from IIT Kanpur and the government suggested the experiment had contributed to a slight easing of pollution. But the scientific community was swift to counter this claim, pointing to a far more plausible actor: the wind.

“It seems like the skies have cleared, but it is because the weather conditions have changed. That’s no credit to the seeding efforts,” says Shahzad Gani, an aerosol scientist at IIT Delhi.

The days following the experiment saw a shift in wind patterns and an increase in wind speed—natural meteorological events that are the primary drivers of pollution dispersal in the region. This phenomenon underscores a fundamental challenge in validating cloud seeding: the “causality problem.” How can you prove the rain you got was from your seeding, and not rain that was already on its way? In this case, with no rain at all, the attribution of cleaner air to the failed experiment was a clear case of post-hoc reasoning.

The cancellation of a second scheduled trial, with IIT Kanpur’s director admitting they would wait for a day with 40-50% cloud moisture, was a tacit admission of the initial attempt’s flawed premise.

A Global History of Hopeful Intervention

India’s foray into weather modification places it in a long, and often contentious, global history. China has the world’s most extensive cloud-seeding program, using it to try to induce rain over arid regions, clear skies for major events like the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and even secure clear weather for political parades. The United Arab Emirates regularly seeds clouds in its pursuit to augment its meager freshwater resources.

However, the scientific consensus on the efficacy of these programs remains guarded. While there is evidence that seeding can enhance precipitation from suitable clouds by perhaps 5-15%, its ability to create rain from scratch is considered negligible. Furthermore, its application for pollution clearance is even less proven. The rain that might fall would only cleanse a localized column of air temporarily, doing nothing to stop the relentless sources of pollution on the ground.

Earlier in 2023, Thailand’s “Royal Rainmaking Project” attempted a different tactic, spraying cold water from planes in the hope of disrupting the warm air layers that trap pollutants—another experimental approach with uncertain outcomes. These efforts highlight a global desperation to find technological end-runs around the hard work of reducing emissions at their source.

Beyond the Quick Fix: Confronting the Real Sources of Smog

The failed cloud seeding experiment serves as a costly distraction from the actual, complex battle against Delhi’s pollution. The toxic smog is a vicious cocktail with several primary ingredients:

- Agricultural Burning: Every autumn, farmers in the neighbouring states of Punjab and Haryana burn the stubble of their harvested rice crops to quickly clear fields for wheat sowing. This practice releases a massive plume of particulate matter that travels directly on the prevailing winds to Delhi.

- Vehicle Emissions: Delhi’s massive fleet of cars, trucks, and motorcycles, many running on dirty fuel, is a constant and significant source of nitrogen oxides and other pollutants.

- Industrial and Construction Pollution: Unregulated emissions from industries and pervasive dust from construction sites add heavy metals and coarse particles to the mix.

Tackling these sources is unglamorous, politically fraught, and requires long-term commitment. It means:

- Providing Farmers Viable Alternatives: Investing in and subsidizing Happy Seeders and other machinery that can manage crop residue without burning, and creating economic incentives for farmers to adopt them.

- Accelerating the Electric Vehicle Transition: Strengthening public transportation and aggressively incentivizing a shift to electric vehicles.

- Enforcing Stricter Regulations: Implementing and, crucially, enforcing emission standards for industries and dust-control protocols at construction sites.

These solutions lack the dramatic appeal of flying planes into the sky. They involve difficult conversations about agrarian economics, urban planning, and corporate accountability. But they are the only interventions proven to work.

The dream of controlling the weather is a powerful one. But as Delhi’s failed cloud seeding trial demonstrates, it is a dangerous fantasy to believe we can simply engineer our way out of a crisis that we have engineered through our own consumption and practices. True clarity will not come from a flare of silver iodide in a dry sky, but from the sustained, collective will to clean up the ground beneath our feet. The solution to the pollution crisis was never in the clouds; it has been, all along, firmly within our grasp.

You must be logged in to post a comment.