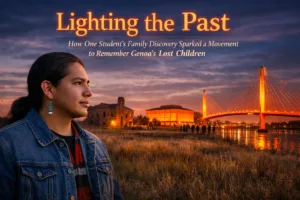

Lighting the Past: How One Student’s Family Discovery Sparked a Movement to Remember Genoa’s Lost Children

Randall Nunez, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln student, embarked on a genealogy journey that led him to discover four of his relatives attended the Genoa Indian Industrial School, part of a federal assimilation policy that stripped Native children of their culture. This personal connection compelled him to organize a large-scale remembrance event, securing sponsorships and university support to illuminate Sheldon Museum of Art, Love Library, and Omaha’s Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge in orange on Feb. 20—a color symbolizing Indigenous resilience and solidarity. Nunez’s efforts honor the children who suffered at Genoa, demonstrate how student leadership can create meaningful change, and ensure these stories are never forgotten through annual remembrance activities supported by Nebraska legislative resolution.

Lighting the Past: How One Student’s Family Discovery Sparked a Movement to Remember Genoa’s Lost Children

The Moment Everything Changed

Randall Nunez stood on empty ground last year, trying to imagine the buildings that once stood there. The wind moved across the Nebraska prairie the same way it had a century ago, when his relatives walked this same earth as children torn from their homes.

“I went to Genoa last year just to see the place,” Nunez recalls. “Seeing the space where my relatives lived, where their culture was stripped from them, made everything I’d read online suddenly real.”

That visit to the former site of the Genoa Indian Industrial School transformed Nunez from a student researching his family tree into something he never expected to become: an organizer, a public speaker, and the driving force behind a remembrance event that will soon illuminate three major Nebraska landmarks in orange light.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

For Nunez, a senior management major in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s College of Business with a minor in Native American studies, the journey began like many genealogy searches—with questions about where he came from.

He didn’t anticipate finding answers that would lead him to a painful chapter of American history. Through the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project, a UNL-led online archive documenting enrollment records and the lives of Native children at the school, Nunez discovered that four of his relatives had attended the institution.

The Genoa Indian Industrial School operated from 1884 to 1934 as part of a federal assimilation policy that separated Native American children from their families. The stated goal was to “kill the Indian to save the man”—a philosophy that systematically stripped children of their tribal languages, their traditional dress, and their cultural practices. For generations of Indigenous families, the boarding school system created wounds that have never fully healed.

For Nunez, finding his relatives’ names in the digital archive was abstract at first—names on a screen, dates in a database. But the knowledge pulled at him until he couldn’t ignore it anymore. He needed to see the place where they had lived.

Walking Where They Walked

The drive to Genoa takes about an hour and a half from Lincoln. Nunez made the trip alone, unsure what he would find or how he would feel when he got there.

What remained of the school wasn’t what he expected. The buildings are largely gone now—just the superintendent’s house still stands, along with a building that once housed the school’s boiler room. The grounds have been reclaimed by grass and time.

But standing there, Nunez felt something shift inside him. The names from the database became people. The historical accounts became personal.

He thought about what his relatives must have experienced—children taken from everything familiar, forbidden to speak their own languages, cut off from their families for years at a time. He thought about their resilience, surviving an institution designed to erase their identities.

“I went to Genoa last year just to see the place,” Nunez said simply. But the visit was anything but simple. It was the beginning of something much larger.

From Personal Discovery to Public Action

When Nunez returned to campus, he carried something new with him—not just knowledge about his family’s past, but a sense of responsibility. He wanted others to understand what happened at Genoa. He wanted the children who suffered there to be remembered.

The opportunity came through Nebraska Legislative Resolution 280, approved unanimously in 2022, which designates Feb. 20 in Nebraska as an annual day of remembrance for the Genoa school. The resolution created a framework for recognition, but it would take individual action to bring that recognition to life.

Nunez began talking with mentors who could help him navigate university processes. Gabriel Bruguier, assistant professor at University Libraries and director of the Genoa Digital Reconciliation Project, had already spent years documenting the school’s history and connecting with descendants. TJ McDowell, assistant vice chancellor and dean of students, understood how student initiatives could create meaningful change on campus.

They helped Nunez understand that remembrance doesn’t happen by accident—it requires coordination, sponsorship, and persistence. Nunez threw himself into learning how to make things happen at a major university.

“I wanted to do something visible, something that would make people stop and ask questions,” Nunez explained. “Not just for my relatives, but for all the children who were there.”

The Meaning Behind the Orange Light

The idea of lighting buildings in orange came from Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation movement, which has used orange to highlight the history and impact of residential schools. The color traces back to Phyllis Webstad, a Northern Secwepemc woman whose new orange shirt was taken from her on her first day at residential school—a story that spawned “Orange Shirt Day” and a broader movement to honor Indigenous children who never came home.

For Nunez, orange represents multiple layers of meaning: solidarity with Indigenous communities across North America, resilience in the face of cultural destruction, and remembrance for those who suffered.

“Lighting the buildings wasn’t just about the lights,” Nunez emphasized. “It was about engaging the university, building awareness and showing that students’ voices matter. If we have a vision, we can take action.”

That vision required months of work—coordinating with university facilities, securing approvals, explaining the significance to people who had never heard of the Genoa school. Nunez also needed funding for the Omaha bridge illumination, which he secured through sponsorship from the Ponca Economic Development Corporation.

Three Landmarks, One Message

On Feb. 20, three Nebraska landmarks will glow orange in remembrance of the Genoa children:

Love Library at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, which houses the Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project and serves as a repository for the documented lives of thousands of Native children.

Sheldon Museum of Art, where the remembrance event will take place, its exterior digitally enhanced with orange hue in promotional materials to represent the illumination.

Omaha’s Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge, spanning the Missouri River and connecting Nebraska to Iowa, its lights burning orange thanks to Ponca Economic Development Corporation sponsorship.

Each location carries its own significance. The library represents the preservation of memory—the careful work of collecting and sharing stories that might otherwise be lost. The museum represents the power of gathering, of community coming together to witness and acknowledge. The bridge spans boundaries, much like the Genoa school drew children from multiple tribes across the region.

A Night of Remembrance

The Feb. 20 event at Sheldon Museum of Art will bring together multiple voices in Indigenous advocacy and education. Judi gaiashkibos, executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs, will offer remarks drawing on decades of work supporting Nebraska’s tribal communities.

A student panel will feature Nunez alongside other leaders from the University of Nebraska Inter-Tribal Exchange—young Indigenous voices carrying forward the work of remembrance and reconciliation. For Nunez, serving as emcee represents both an honor and a responsibility.

“It’s one thing to read about history in a classroom,” he reflected. “It’s another thing to stand up in front of people and say, ‘This happened to my family. This happened to my people. And we need to remember.'”

The event is free and open to the public—an invitation to the wider community to participate in this act of collective memory.

The Power of Student Leadership

What makes Nunez’s story remarkable isn’t just the personal discovery or the successful event planning. It’s what his journey reveals about the potential for student leadership to create meaningful change.

Bruguier, who has worked with numerous students on the Genoa Digital Reconciliation Project, sees Nunez’s initiative as part of a larger shift. “Students today are hungry for connection to history, but they also want to act on what they learn,” Bruguier noted. “Randall didn’t just want to know about his relatives—he wanted to honor them in a way that would reach other people.”

McDowell, who has mentored countless student leaders, emphasized the importance of supporting student visions rather than directing them. “My role was to help Randall understand how the university works and connect him with the right people,” McDowell explained. “But the vision was entirely his. That’s where the power comes from—when students own the work.”

The process wasn’t always smooth. University bureaucracies move slowly. Funding requires proposals and justification. People need education about why the Genoa school matters and why orange lighting is an appropriate tribute. Nunez navigated each challenge with growing confidence, learning that persistence matters as much as passion.

Looking Forward: A Vision for Growth

As the Feb. 20 event approaches, Nunez is already thinking about what comes next. He envisions the building lighting expanding each year—more landmarks across Nebraska illuminated in orange, more communities participating in remembrance.

He hopes Indigenous student organizations across the state will take up the cause, elevating the history of boarding schools in their own communities and creating new traditions of memory. The Genoa school drew children from numerous tribes across the Great Plains and beyond—Omaha, Ponca, Winnebago, Santee Sioux, and many others. The remembrance should reflect that reach.

“There’s so much more to do,” Nunez acknowledged. “One night of lighting buildings doesn’t fix anything. But it’s a start. It’s a way of saying we haven’t forgotten. We’re not going to let these stories disappear.”

For Nunez personally, the work has deepened his understanding of what it means to be Indigenous in America today. The boarding school era officially ended decades ago, but its effects ripple through generations—families separated from their languages, their ceremonies, their connections to land and community. Healing requires acknowledgment, and acknowledgment requires remembrance.

“Seeing my relatives’ names in the records, standing on the grounds where they lived, and now seeing the campus glow for remembrance—it’s a way to honor them, to acknowledge their resilience, and to ensure their stories are never forgotten,” Nunez said.

Why Remembrance Matters

For those who might wonder why a century-old school deserves annual remembrance, Nunez offers a clear answer: because the children who lived there were real people, not statistics. They had names, families, dreams. They endured experiences that shaped the rest of their lives and the lives of their descendants.

The Genoa Indian Industrial School was one of hundreds of similar institutions across the United States and Canada, part of a federal policy that continued well into the twentieth century. The trauma didn’t end when the schools closed—it passed through generations, creating complex legacies that Indigenous communities still navigate today.

Remembrance, then, is not about dwelling in pain but about acknowledging truth. It’s about recognizing that policies justified as benevolent caused real harm. It’s about honoring those who survived and those who didn’t, and committing to a future that respects Indigenous sovereignty and dignity.

Nunez’s journey from genealogy researcher to remembrance organizer demonstrates how personal connection can spark public action. One person’s desire to understand his family’s past has illuminated three major landmarks and created a space for community gathering and reflection.

The Ongoing Work of Reconciliation

The Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project continues to grow, adding records and stories as descendants come forward with family histories. Bruguier and his team work with tribal communities to ensure that the documentation serves Indigenous interests and respects cultural protocols.

For Nunez, the project remains a vital resource—both for his own continued learning and for the education of others. He encourages anyone interested in the Genoa school’s history to explore the digital archive and consider what connections they might find.

“Your family might be in there too,” he pointed out. “So many Native families across the Midwest have connections to Genoa that they don’t even know about. The records are there, waiting to be discovered.”

That discovery can be painful, as Nunez knows firsthand. But it can also be transformative—turning abstract history into personal story, passive knowledge into active remembrance.

A Legacy of Light

On Feb. 20, when the buildings glow orange across Nebraska, Nunez will be at Sheldon Museum of Art, welcoming attendees and introducing speakers. He’ll think about his four relatives who walked the grounds at Genoa. He’ll think about all the other children whose names appear in the digital archive. He’ll think about the generations of Indigenous families shaped by the boarding school experience.

And he’ll think about what comes next—the work still to be done, the stories still to be told, the remembrance still to be maintained.

“Lighting the buildings wasn’t just about the lights,” he said. “It was about engaging the university, building awareness and showing that students’ voices matter. If we have a vision, we can take action.”

Randall Nunez had a vision. He took action. And now, across three Nebraska landmarks, that vision will burn orange—a reminder that history lives in the present, that descendants carry the stories of their ancestors, and that remembrance is not passive but active, not finished but ongoing.

The children of Genoa are not forgotten. Their names are recorded. Their resilience is honored. And one student’s journey to know his family has lit a path for others to follow.

You must be logged in to post a comment.