Justice Delayed: How a High Court Ruling on Palestine Action Has Halted a Major Criminal Damage Case

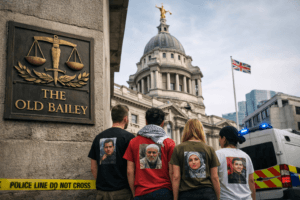

A court case against four pro-Palestine protesters accused of causing over £1 million in damage to the Moog defence factory in Wolverhampton has been postponed after a High Court ruling deemed the government’s ban on the Palestine Action group unlawful. The defendants—Iain Evans, Hisham Alkhamesi, Bea Sherman, and Hana Yun Stevens—were due to enter pleas at the Old Bailey but secured an adjournment until 27 February to consider the judgment’s implications. The High Court had found that then-Home Secretary James Cleverly made legal errors in proscribing Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation, failing to properly distinguish between attempts to influence government and disrupting commercial operations. The four activists, who allegedly climbed onto the factory roof in August 2025 wearing T-shirts of Palestinians they believe were killed by Israeli forces, remain in custody ahead of a possible three-week trial starting 8 June at Birmingham Crown Court.

Justice Delayed: How a High Court Ruling on Palestine Action Has Halted a Major Criminal Damage Case

The Intersection of Protest, Law, and Political Definition

On a damp Friday morning at the Old Bailey, what should have been a straightforward plea hearing for four activists accused of causing over £1 million in damage to a defence manufacturing facility took an unexpected turn. The proceedings ground to a halt not because of new evidence or procedural errors, but because of a seismic legal development that had occurred just hours earlier in another London court—one that fundamentally challenged how the British legal system classifies protest groups.

Iain Evans, 32, Hisham Alkhamesi, 23, Bea Sherman, 23, and Hana Yun Stevens, 23, appeared via video link from custody, each facing a single count of criminal damage stemming from an incident at the Moog Aircraft Group factory in Pendeford, Wolverhampton, on 26 August 2025. But when their counsel requested an adjournment to consider the implications of a freshly delivered High Court judgment, Mrs Justice Cheema-Grubb found herself in an unusual position—forced to pause proceedings while the legal ground shifted beneath everyone’s feet.

The August Break-In: What Actually Happened

To understand the significance of Friday’s adjournment, we need to go back to that August morning when staff arriving at the Moog factory were confronted with a scene that defied normal expectations of industrial estate life. Security footage and social media videos later released by the group calling themselves “Palestinian Martyrs for Justice” showed a four-wheel drive vehicle ramming through gates, individuals releasing a red flare, and activists climbing ladders onto the factory roof.

The damage was substantial—multiple skylights destroyed, solar panels rendered inoperable, and production likely disrupted. Staffordshire Police would later put the figure at more than £1 million, a sum that reflects not just the physical damage but the operational impact on a facility that produces components for the aerospace industry.

But for the activists, the financial cost was never the point. In the video they released, one participant explained their motivation with striking clarity: “We are Palestinian Martyrs for Justice and each of us here today on the roof of Moog are wearing a T-shirt of one of the martyrs that have been murdered by Israel in the genocide.”

The target was chosen deliberately. Moog manufactures equipment that finds its way onto F-35 fighter jets—aircraft used by the Israeli government in its military operations in Gaza. For the protesters, damaging the factory was not vandalism but a moral imperative, an attempt to physically disrupt the supply chain of what they view as weapons of war being used against civilians.

The Legal Bombshell: Why Palestine Action’s Ban Was Overturned

The reason Friday’s hearing collapsed lies in a separate legal battle that has been quietly unfolding in the background—one that strikes at the heart of how the British government defines and responds to political protest.

Earlier this year, the Home Office had taken the unusual step of proscribing Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation. Proscription is one of the government’s most powerful tools—it makes belonging to, supporting, or displaying symbols of a banned group a criminal offence. The decision to add Palestine Action to the same list as Al-Qaeda and ISIS was controversial from the start, raising questions about where to draw the line between violent protest and terrorism.

Palestine Action challenged the ban in court, and on the morning of the Moog defendants’ hearing, Mrs Justice Cheema-Grubb and Mr Justice Johnson delivered their verdict: the Home Office’s decision was unlawful. The judges found that then-Home Secretary James Cleverly had made legal errors when he concluded there was “reasonable grounds to believe” the group was concerned in terrorism.

The judgment hinged on a crucial distinction. While the Home Office had pointed to property damage, vandalism, and disruption caused by Palestine Action, the court noted that the group’s methods—occupations, blockades, and damage to property—did not meet the statutory definition of terrorism. The Terrorism Act 2000 defines terrorism as action that involves serious violence against a person, endangers life, or creates serious risk to health or safety, all designed to influence the government or intimidate the public.

Crucially, the court found that Cleverly had failed to properly distinguish between actions intended to “influence the government” (which could potentially meet the terrorism definition) and actions intended to “directly prevent or disrupt” defence companies’ operations (which might not). The judges also noted that the Home Secretary hadn’t adequately considered whether the group’s methods were “democratic” or “unlawful”—a distinction that goes to the heart of how we categorise civil disobedience.

What This Means for the Four Defendants

For Evans, Alkhamesi, Sherman, and Stevens, the timing of this judgment could hardly be more significant. Their counsel’s request for an adjournment wasn’t a delaying tactic—it was a recognition that the legal landscape had fundamentally shifted.

The High Court ruling doesn’t directly determine the outcome of the criminal damage case. The four are charged with criminal damage, not terrorism offences. But the judgment changes the context in which their actions will be viewed, both by the court and by the public.

When defendants engage in politically motivated actions, the way their cause is characterised matters. Being labelled as members of a proscribed terrorist group carries a stigma that extends far beyond the courtroom. It affects how judges and juries perceive their actions, their motivations, and their moral standing. The High Court’s ruling that Palestine Action should never have been banned in the first place strips away that characterisation, allowing the defendants to present themselves as political protesters rather than terrorists.

The adjournment until 27 February gives their legal team time to consider how the judgment might be used in their defence. Could it support an argument that their actions, while unlawful, were legitimate political protest? Might it influence sentencing if they’re convicted? These are questions that will now be carefully considered.

The Human Cost of Legal Delay

While the legal arguments play out, four young people remain in custody. Evans, from Shipley in West Yorkshire; Alkhamesi, from Hinckley in Lincolnshire; Sherman, from Hassocks in West Sussex; and Stevens, from south-west London—all now facing the prospect of a three-week trial at Birmingham Crown Court beginning 8 June, before a High Court judge.

The human reality behind the legal proceedings is easy to overlook. These are individuals who made a choice—a choice to commit criminal damage in service of a cause they believe in passionately. However one judges that decision, it’s impossible to deny the conviction behind it. The activists on that roof in August were wearing T-shirts bearing the names of Palestinians they believed had been killed by Israeli forces—a gesture that transformed their protest from abstract politics into something deeply personal.

Whether one agrees with their methods or their cause, the sight of young people facing years in prison for damaging property—while the destruction they protest continues unabated—raises uncomfortable questions about proportionality and moral consistency.

The Broader Implications for Protest in Britain

The Palestine Action case, both the proscription challenge and the criminal proceedings against these four individuals, arrives at a moment of intense debate about the boundaries of legitimate protest in the United Kingdom.

The last few years have seen successive governments grapple with how to respond to increasingly bold and disruptive protest movements. Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, Insulate Britain, and now Palestine Action have all pushed against the limits of what the law permits, using direct action and property damage to draw attention to their causes. The response has been a steady expansion of police powers and tougher sentencing for protest-related offences.

But the High Court’s ruling against Palestine Action’s proscription suggests there are limits to how far the government can go in categorising protest as terrorism. The judges’ careful parsing of what constitutes “influencing the government” versus “disrupting commercial operations” may provide a template for future challenges. If damaging a defence contractor’s factory to prevent weapons reaching a conflict zone isn’t terrorism, what is? The court’s answer, essentially, is that it depends on the intended target of the influence—government or private sector.

This distinction may seem technical, but it has profound implications. It suggests that activists who target government buildings or officials might face terrorism charges, while those who target private companies operating in controversial industries might not. Whether that distinction makes moral or practical sense is now a matter for Parliament and the courts to debate.

The F-35 Connection: Why Wolverhampton Matters in Gaza

For readers wondering why a factory in Pendeford, Wolverhampton, became the target of pro-Palestine protest, the answer lies in the global supply chains of modern warfare. The F-35 Lightning II is a joint strike fighter used by the United States, the United Kingdom, Israel, and other allies. It’s one of the most advanced military aircraft in existence, and its production involves companies across the Western world.

Moog’s Wolverhampton facility produces primary flight control actuators for the F-35—components that help control the aircraft’s movement. When Israeli F-35s drop bombs on Gaza, they do so using equipment manufactured in part by British companies. For Palestine Action and its supporters, this creates a direct line of responsibility from Wolverhampton to Gaza.

This argument—that British companies are complicit in alleged war crimes by supplying weapons used by Israel—has gained traction in recent years. Legal challenges have sought to suspend arms export licences, and protests have targeted numerous defence companies across the country. The activists on the Moog roof were making a physical argument that legal and political channels had failed to address.

Looking Ahead: The February Hearing and Beyond

With the case now adjourned until 27 February, all eyes will turn to what happens when the four defendants next appear in court. By then, their legal team will have had time to digest the High Court judgment and determine how best to deploy it in their defence.

The timing is tight. With a potential trial start date of 8 June, the February hearing will need to resolve any outstanding issues and, if the defendants intend to plead not guilty, set the groundwork for what promises to be a closely watched trial.

For the defendants, the coming months will be spent in custody, awaiting their fate. For their families and supporters, there is the agony of uncertainty. And for the wider public, the case offers a window into some of the most difficult questions facing any democratic society: Where does legitimate protest end and criminality begin? When does political violence become terrorism? And how should the law respond to those who break it in service of a cause they believe transcends legal obligation?

The judge’s decision to adjourn was described as allowing the defence to raise “an argument that is not right and proper to raise.” That careful phrasing hints at the complexity beneath the surface. In February, we’ll begin to see what that argument looks like—and perhaps gain some clarity on how British justice navigates the treacherous waters where law, politics, and morality meet.

One thing is certain: the activists on that Wolverhampton roof achieved something remarkable. They forced a conversation about weapons, war, and responsibility that might otherwise never have happened. Whether the courts ultimately convict or acquit them, that conversation will continue—in courtrooms, in Parliament, and in the public square where the boundaries of conscience are forever being tested.

You must be logged in to post a comment.