India’s Thirst: How a Water Crisis is Redefining the Future of Beverage Giants

India’s Thirst: How a Water Crisis is Redefining the Future of Beverage Giants

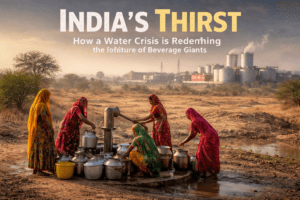

In the arid landscape of Alwar, Rajasthan, the earth is parched and hope is often measured in litres. Here, women gather around a lone borewell, a stark image of a daily struggle that stands in silent contrast to the sprawling, high-tech bottling plants not far away. This is the frontline of a complex battle between survival, industry, and growth, where some of the world’s most iconic beverage companies are finding that their most critical ingredient is also their greatest liability: water.

India’s water crisis is not a future spectre; it is a present, grinding reality. Holding 17% of the world’s population with just 4% of its freshwater, the nation’s economic ambitions are on a collision course with ecological limits. For global beverage behemoths like Diageo, Heineken, Carlsberg, and Coca-Cola, this scarcity is transforming operational playbooks, investor risk assessments, and community relations in one of their most crucial growth markets.

The Regulatory and Geographic Quagmire

The challenge in Rajasthan is a potent cocktail of geography and regulation. Two-thirds of the state is desert, and its groundwater extraction rates are among India’s highest. Furthermore, India’s complex alcohol laws create a unique pressure point: liquor cannot cross state borders without special permits, forcing companies to establish production facilities in every state where they want to sell. There is no option to centralise operations in water-rich regions. If you want the Rajasthani market, you must set up shop in Rajasthan—aquifer levels notwithstanding.

This places these multinationals directly in the heart of water-stressed communities. The Alwar district, an industrial hub about 150 km from Delhi, is classified as “over-exploited.” Government data reveals a chilling metric: groundwater is being extracted at nearly twice the rate nature can replenish it. While industry consumes only about 2% of Rajasthan’s water, its presence in these critical zones makes it a visible and often controversial player.

The Permit vs. Perception Divide

Reuters’ analysis of 2025 permits reveals a startling figure: brewers in Alwar are authorised to draw up to 4.6 million litres of groundwater daily. Heineken alone tops the list at 1.2 million litres. Companies rightly point out that a single coal-power plant or textile unit may use far more. But in villages like Salpur, nestled beside the industrial cluster, this data is an abstraction against a harsh daily reality.

Here, water is a luxury, piped into homes just once a week. Farmers like village head Imran Khan invest small fortunes to lay kilometres of private pipeline and pay hourly rates for borewell water to irrigate their fields. In this context, the sight of tankers leaving brewery gates—even if legally permitted—fuels a deep-seated sense of injustice. “They are making alcohol there but locals do not have enough water to drink,” says Alwar resident Haider Ali, who last year took several companies to court over alleged unauthorized extraction. While a court-appointed team found the companies in compliance, the case underscores a volatile gap between legal permits and social license to operate.

The Corporate Replenishment Gambit

Faced with this, the corporate response has shifted from mere efficiency to a mantra of “water replenishment.” Each major player now champions a public goal of returning 100% of the water used in production to the local watershed. This is more than PR; it’s a fundamental reimagining of their resource relationship.

Their efforts are multifaceted:

- Technical Innovation: Inside the plants, the focus is on radical efficiency. Diageo’s Alwar facility, for instance, uses air instead of water to rinse bottles and recycles 100% of its wastewater. The goal is a 40% reduction in consumption.

- Community Infrastructure: Outside the factory walls, companies fund watershed management projects. Diageo has built small dams (check dams) and planted thousands of trees in Salpur. Heineken, through NGO partners like the S M Sehgal Foundation, works on desilting village ponds and installing rooftop rainwater harvesting systems.

- Aquifer Recharge: This is the core of the “replenishment” promise. By creating structures to capture monsoon rains and direct them back into the ground, they aim to offset their withdrawals.

Simon Boas Hoffmeyer of Carlsberg argues this approach should redefine the industry’s role: “If everybody did that, the industry’s share of the issue would be very, very small.”

The “Scope for More” Dilemma

Yet, a critical question remains: Is it enough? Subhransu Kumar Bebarta of the S M Sehgal Foundation, which implements Heineken’s projects, offers a telling assessment. While acknowledging the positive local impact, he notes, “There is always scope for more.” The interventions, though valuable, are often localized—a rehabilitated pond here, a few new borewells there. They can improve a village’s access but may not systemically reverse the district’s over-exploited status.

The crisis demands scale. The 2020 government order for over-exploited areas mandates the “latest water-efficient technologies,” but lacks specificity. The tension is between corporate sustainability projects and the need for large-scale, state-driven infrastructure: massive canal networks, state-wide rainwater harvesting mandates, and a revolution in water-intensive agriculture, which consumes over 80% of Rajasthan’s water.

A Microcosm of a Macro Risk

Alwar is not an anomaly; it’s a preview. Coca-Cola’s internal water security plan, reviewed by Reuters, starkly outlines the financial risk. It identifies nine of its Indian plants in areas of high water stress and estimates future water procurement costs could balloon by up to $2.7 million annually. This is a direct hit to the bottom line. The ghost of the past looms, too—Coca-Cola was forced to close a plant in Kerala in 2005 after mass protests over groundwater depletion, a precedent no company can ignore.

The water crunch is becoming a material factor for ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investors. It intertwines environmental stewardship (E), community relations and human rights (S), and long-term operational viability (G). A company that fails to secure its water future in India isn’t just risking reputational damage; it’s risking its entire business model in the world’s most populous nation.

The Path Forward: Beyond the Factory Fence

The future for beverage giants in India will depend on a dramatic evolution of their role. They must move from being efficient water users to becoming recognized water stewards within their watersheds. This requires:

- Transparent Collaboration: Sharing water data openly with communities and working with them on joint management plans, not just corporate-designed projects.

- Agricultural Partnership: Engaging with the farming sector—the largest water user—to promote drip irrigation and less thirsty crops. Some companies are exploring this, but it needs to become a core strategy.

- Advocacy for Policy: Using their influence to advocate for stronger, clearer, and better-enforced state-wide water management policies that address all sectors.

The women at the borewell in Alwar are not just a powerful image; they are the ultimate stakeholders. For Diageo, Heineken, Carlsberg, and their peers, the real test is whether their “replenished” water ever reaches that borewell. The answer will determine not only the sustainability of their Indian operations but also the very legacy they leave in a country where every drop tells a story of scarcity, equity, and survival. In India’s thirst, they are finding that their most important brew is not beer or soda, but trust—and it is proving far more difficult to bottle.

You must be logged in to post a comment.