India’s Literary Carnival: The Paradox of 100 Book Festivals in a Nation of Non-Readers

India’s Literary Carnival: The Paradox of 100 Book Festivals in a Nation of Non-Readers

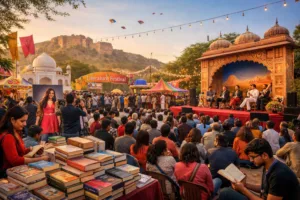

India’s literary calendar is a vibrant, crowded map. Each winter, over 100 literature festivals bloom from Jaipur’s grand palaces to the unlikely grounds of smaller towns. Yet, the country’s reading statistics tell a different story. The average English-language book sells only 3,000-4,000 copies, with a title considered a bestseller if it crosses 10,000. The image of a nation enchanted by stories—a land of epics—stands in contrast with the reality that buying and reading books remains a luxury for many. This apparent contradiction is at the heart of modern Indian literary culture, revealing a society where literature has transformed from a private pursuit into a public, social spectacle.

The Roots of the Reading Gap

Understanding why festivals thrive despite low reading rates requires examining the barriers to reading in India.

- Economic and Social Realities: For much of the country’s vast middle and lower-middle class, purchasing a book is a significant expense. This economic constraint intersects with leisure habits; a standard family outing is more likely to be a trip to a shopping mall than a bookstore. A generational shift toward digital entertainment has further crowded out reading time. India is one of the world’s largest consumers of mobile data, with short videos, gaming, and social media reels filling leisure hours.

- Functional vs. Pleasurable Reading: India’s publishing industry is robust, but its focus is largely utilitarian. The market is valued at around Rs. 80,000 crore (US$ 9.3 billion), yet it is dominated by educational and academic content. This reflects a culture where reading is primarily linked to exams and career advancement rather than leisure or intellectual curiosity. This creates a paradox: a nation that publishes 90,000 titles a year (ranking 10th globally) produces a populace for whom reading for pleasure is not a deeply ingrained habit.

- The Legacy of Orality: Some observers, like author Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr., suggest the strong oral storytelling tradition might be a factor. Epic tales like the Mahabharata and Ramayana are known and passed down through performance, conversation, and television, not necessarily through books. This creates a cultural intimacy with stories that doesn’t always translate into a personal reading habit.

The Festival Formula: More Carnival, Less Canon

Given these barriers, the success of literature festivals seems perplexing. The answer lies in their deliberate evolution into something far beyond book launches and author readings. They have become holistic cultural carnivals.

- The “Masala” Mix: Festival organizers consciously craft a diverse programme. At the Banaras Lit Fest, for example, a session on “screens versus books” shares the schedule with stand-up comedy, fashion shows, mime performances, and classical music concerts by Grammy-winning artists. As the festival’s president notes, you must provide “a ‘masala’ mix with a bit of something for everyone”. This approach caters to the broad Indian preference for lively, bustling social settings over hushed, decorous ones.

- Celebrity and Spectacle: The presence of Bollywood stars, famous sportspersons, and influential politicians is a major draw. These figures guarantee media coverage and pull in crowds who may have little interest in literature but want to see a celebrity. Critics argue this has turned some major festivals into “red-carpet events” where the celebration of celebrity overshadows the engagement with ideas.

- Accessibility and Aspiration: Many festivals, especially smaller regional ones, are free to enter. This removes the economic barrier to participation. For attendees, being seen at a prestigious cultural event carries social capital—it’s a chance to be part of a “cool,” intellectual crowd. The festival becomes a social experience, a weekend activity akin to visiting a fair, where the book is the backdrop, not the main event.

A Comparative Look at India’s Literary Festival Landscape

| Festival Type | Primary Appeal | Typical Features | Audience Engagement with Books |

| The Mega-Festival (e.g., Jaipur) | Spectacle & Celebrity | Bollywood stars, political figures, huge crowds (400,000+), music concerts, lavish launches. | Often superficial; focused on selfies and seeing famous people. Books are a secondary prop. |

| The Regional Carnival (e.g., Banaras) | Cultural & Social Experience | Local artists, handicraft stalls, food, regional language focus, free entry, school participation. | Incidental but potential for sparking interest, especially among youth. More community-focused. |

| The Niche/Independent Festival | Literary Depth & Ideas | Smaller, curated author line-ups, focused thematic discussions, quieter atmosphere. | High; attended by dedicated readers seeking substantive conversation. Less commercial spectacle. |

The Publishing Industry’s Double-Edged Sword

The festival boom occurs alongside a complex publishing ecosystem.

- A Multilingual Powerhouse: While English-language books dominate elite discourse and international attention, 45% of non-textbook trade books are sold in Indian regional languages like Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, and Kannada. This creates vibrant, self-contained literary worlds. An author like Banu Mushtaq can be a giant in Karnataka, writing in Kannada about Muslim women’s lives, yet remain unknown nationally until her work is translated into English, as happened before her International Booker Prize win in 2025.

- The Translation Chasm: This highlights a critical bottleneck. As American author Dan Morrison observed at the Varanasi festival, “You feel that something great could be cooking in a state but I can’t smell it, I won’t know it, until it’s translated into English”. The lack of a robust translation infrastructure keeps regional literature local, even as festivals try to democratize access.

- Commercial Pressures: The industry faces soaring production costs, with paper prices nearly doubling post-pandemic. This forces publishers to be risk-averse, focusing on surefire educational texts or celebrity memoirs rather than experimental literary fiction. In this climate, festivals become vital, high-visibility marketing platforms for the few trade books that do get published.

Criticisms and Defenses: The Value of the Spectacle

The transformation of litfests has not been without its critics. Disillusioned attendees lament the decline of intellectual substance.

- Commodification of Culture: Critics see festivals as having become commercial spectacles, sponsored by corporations and turned into profitable lifestyle events. Sessions are often described as superficial, with authors promoting their latest work rather than engaging in deep debate. The “literary establishment” is accused of complicity, using festivals as a circuit for visibility and sales.

- The “Dumbing Down”: There is a concern that festivals cater to shortened attention spans. Author Pavan Varma notes a trend where audiences want “neatly packaged, short, simplified, easily comprehensible, capsuled… texts” rather than engaging with complex, lasting literary value.

- A Seed of Hope: Despite the criticisms, defenders see inherent value. For schoolchildren bussed in, a chance encounter with an author or a topic can ignite a lifelong curiosity. For a public where books are scarce, festivals provide a tangible, accessible encounter with literary culture. As one young literature student at the Banaras fest put it, even if a handful of people hear something they remember for life, it’s worth it. American author Dan Morrison concurs: “At least you’re around some culture that is not a screen”.

Conclusion: A Celebration in Search of Readers

The story of India’s 100 literature festivals is not a simple tale of literary passion. It is a narrative about cultural aspiration meeting commercial reality. The festivals thrive because they have adapted, offering a social, entertaining, and accessible gateway to a world that the act of solitary reading often fails to reach. They are less a sign of a reading nation and more a vibrant, chaotic, and sometimes contradictory experiment in making literature relevant in a rapidly changing society.

Whether this model cultivates a new generation of readers or merely provides a delightful distraction remains an open question. The festivals themselves are a lively, arguing text—one that reflects India’s own struggle to balance its rich intellectual heritage with the relentless pressures and pleasures of the modern world. They may not be creating a nation of bibliophiles, but they are undeniably keeping the conversation about books, ideas, and stories alive in the public square.

You must be logged in to post a comment.