India’s Literacy Crossroads: Can National and State Ambitions Converge?

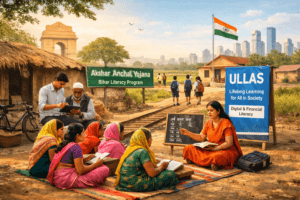

India’s ambitious national goal of achieving 100% literacy by 2030 through the ULLAS scheme, which promotes holistic, skill-based learning, faces a critical hurdle in Bihar, a state with nearly 2 crore non-literate adults. Bihar’s reluctance stems from its long-running state-led Akshar Anchal program, which it argues is better tailored to its marginalized communities, leading to a standoff over fund utilization and implementation.

This impasse highlights a deeper tension between centralized national standardization and state autonomy, threatening the nationwide mission’s success. The solution lies not in forcing a replacement but in finding pragmatic convergence—integrating Akshar Anchal’s grassroots infrastructure with ULLAS’s expanded curriculum and certification framework—through cooperative federalism, performance-linked incentives, and a special focus on bridging Bihar’s severe gender literacy gap.

India’s Literacy Crossroads: Can National and State Ambitions Converge?

The quest for 100% literacy by 2030, a cornerstone of India’s National Education Policy and its commitment to global development goals, faces a critical test in the fertile plains of Bihar. While national schemes like ULLAS (Understanding Lifelong Learning for All in Society) celebrate successes in several states, the reluctance of Bihar—home to nearly two crore non-literate adults—to participate has created a significant roadblock. This standoff is more than an administrative tussle; it is a complex narrative about federal cooperation, the evolving definition of literacy, and the challenge of uplifting a region burdened by historical educational deficits.

The ULLAS Vision: Redefining Literacy for a New India

Launched in 2022, the ULLAS scheme represents a paradigm shift in India’s approach to adult education. Moving beyond the traditional metric of merely signing one’s name, ULLAS champions a holistic, functional literacy. Its expanded definition, formalized in mid-2024, encompasses foundational reading, writing, and numeracy, integrated with digital literacy, financial literacy, and crucial life skills. This aligns with the National Education Policy 2020’s vision of creating not just literate individuals, but empowered citizens capable of navigating the complexities of the modern world.

The scheme’s operational model is built on community-driven volunteerism. It mobilizes students, teachers, Anganwadi and ASHA workers to identify non-literate individuals aged 15 and above through door-to-door surveys. Learning occurs through a blend of online resources on the ULLAS app and offline community classes, culminating in the Foundational Literacy and Numeracy Assessment (FLNAT). Successful certification declares an individual literate under this new, comprehensive standard.

The progress in some regions has been notable. States and Union Territories like Himachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Goa, Tripura, and Ladakh have already been declared fully literate under ULLAS, having surpassed the benchmark of 95% literacy. Nationally, over 77 lakh learners had appeared for the FLNAT by mid-2024, demonstrating the scheme’s reach.

Table: Foundational Literacy and Numeracy Assessment (FLNAT) under ULLAS

| FLNAT Round | Date | States/UTs Participated | Learners Appeared | Pass Percentage |

| First | Mar 2023 | 11 | ~22.37 Lakh | 91.27% |

| Second | Sep 2023 | 13 | ~17.57 Lakh | 89.64% |

| Third | Mar 2024 | 23 | ~33.29 Lakh | 88.60% |

Source: Compiled from ULLAS implementation data

The Bihar Conundrum: Scale of the Challenge

Bihar’s significance to the national mission is underscored by stark statistics. With a literacy rate of 74.3% for persons aged seven and above (2023-24), it ranks among the lowest in the country, ahead of only Andhra Pradesh. The gender gap is pronounced: male literacy stands at 82.3%, while female literacy is just 66.1%. Critically, the state is home to an estimated 2 crore non-literate individuals in the 15-59 age group, a staggering 1.32 crore of whom are women.

This educational lag has deep historical roots. From a literacy rate of 13.45% at Independence, Bihar climbed to 61.8% by the 2011 Census, but it consistently remained at the bottom of India’s rankings. The disparity is also geographical. While urban Patna boasts a literacy rate above 83%, districts like Kishanganj and Araria struggle near 61-65%. For India to credibly claim near-universal literacy, progress in Bihar is not just important—it is indispensable.

The Standoff: ULLAS vs. Akshar Anchal

The central government has approved approximately ₹35 crore for Bihar under ULLAS, with an initial installment of ₹16 crore (central share) released in 2023. However, the state has not utilized these funds, failing to transfer them to the mandated Single Nodal Agency or submit annual implementation plans. The Centre has flagged these issues, even warning of a 7% interest penalty on the delayed transfers.

Bihar’s resistance stems from its long-running Akshar Anchal Yojana. Operational for about 15 years, this state-funded scheme targets the most marginalized: Dalits, Mahadalits, minorities, and Extremely Backward Classes, with a special focus on women aged 15-45. Its methodology involves Shiksha Sevaks and Talimi Markaz (educational centres) conducting regular classes, with biannual literacy examinations.

The state government argues that Akshar Anchal, with its established institutional framework and larger financial outlay, makes ULLAS redundant. Recent announcements to provide tablets and smartphones to Vikas Mitras and Shiksha Sevaks under this scheme further indicate a commitment to strengthening its own digital infrastructure rather than adopting the central alternative.

From the ground, the human impact of Akshar Anchal is tangible. As reported in Patna, over two lakh women recently took the scheme’s basic literacy exam. For women like Geeta Devi (45), who learned to write her name for the first time with her grandsons’ help, or Savita Bharti (40), who can now read documents independently, the scheme represents profound personal empowerment.

The Core Tensions: Beyond Administrative Logjam

This impasse reveals deeper fissures in India’s governance model:

- Cooperative Federalism vs. State Autonomy: Education is on the Constitution’s Concurrent List, demanding collaboration. Bihar’s stance tests this principle, highlighting a tension between national standardization and state-specific solutions.

- Uniformity vs. Contextualization: ULLAS offers a standardized, measurable framework with national certification. Bihar advocates for Akshar Anchal, which it perceives as better tailored to its unique social hierarchy and historical deprivation.

- The Evolving Goal of Literacy: The conflict is also philosophical. Is literacy a standardized national credential (as per ULLAS) or a more localized tool for immediate social empowerment (as emphasized by Akshar Anchal’s focus on marginalized women)?.

Pathways to Convergence: A Possible Way Forward

A binary choice between the two schemes is unlikely to yield results. The solution lies in creative integration that respects both national objectives and ground realities.

- Framework Convergence, Not Replacement: Instead of insisting Bihar replace Akshar Anchal, the Centre could work to align the state’s scheme with the broader ULLAS framework. Akshar Anchal’s grassroots teaching infrastructure could be used to deliver a curriculum that incorporates ULLAS’s components of digital and financial literacy, while the state’s biannual tests could be harmonized with the FLNAT for national certification.

- Leverage Bihar’s Digital Push: The state’s recent investment in providing tablets to Vikas Mitras and smartphones to Shiksha Sevaks presents an opportunity. These devices could be used to access the ULLAS app and digital resources, creating a hybrid model that uses state resources for a national-standard learning outcome.

- Performance-Linked Bridge Funding: The central government could create a special incentive fund, released not as a standard allocation but upon achieving agreed-upon milestones (e.g., number of learners certified via FLNAT). This would maintain accountability to national standards while respecting the state’s operational model.

- Hyper-Focus on the Gender Gap: Any convergence plan must prioritize Bihar’s massive population of non-literate women. Schemes can be integrated to create a special sub-mission with enhanced support for female learners, linking literacy to other empowerment initiatives related to health, livelihoods, and legal awareness.

Conclusion

India’s journey to 100% literacy by 2030 is a formidable challenge where statistical goals meet complex social and political realities. The standoff between the Centre’s ULLAS and Bihar’s Akshar Anchal is a microcosm of this larger journey. It underscores that literacy is not merely a technical problem of pedagogy and funding, but a deeply political question of trust, jurisdiction, and contextual relevance.

The way forward cannot be through coercion or insistence on a one-size-fits-all model. It requires pragmatic diplomacy and flexible governance. By finding a formula that allows Bihar to build on its existing institutional strength while progressively aligning with national standards and outcomes, India can turn its biggest literacy challenge into a transformative success story. The goal is not merely to make Bihar participate in ULLAS, but to ensure that every non-literate individual in Bihar—and across India—gains the foundational skills to lead a life of dignity and opportunity. The clock is ticking to 2030, and the lesson is clear: national ambitions can only be realized through cooperative, not combative, federalism.

You must be logged in to post a comment.