India’s Deep-Sea Gambit: Securing the Pacific’s Mineral Fortune for a High-Tech Future

India has solidified its position as a key player in the future of deep-sea mining by signing a second 15-year contract with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), granting it exclusive rights to explore polymetallic sulphides in the Indian Ocean. This move, making India the first country to hold two such contracts for these specific deposits, is a strategic gambit to secure the immense concentrations of copper, zinc, gold, and silver found on the ocean floor, which are critical for clean energy technologies and high-tech manufacturing.

While this enhances India’s energy security and economic ambitions, it also places the nation at the center of a global debate, balancing the immense technological promise and economic potential of harvesting these resources against the significant and unresolved environmental risks posed to the fragile ecosystems of hydrothermal vents.

India’s Deep-Sea Gambit: Securing the Pacific’s Mineral Fortune for a High-Tech Future

Meta Description: India cements its status as a deep-sea mining powerhouse with a new ISA contract. We explore the strategic, economic, and environmental implications of the race for polymetallic sulphides.

In the silent, crushing depths of the Indian Ocean, far beyond the reach of sunlight, a new frontier of geopolitics and resource economics is being staked out. The recent announcement that India has signed a landmark 15-year contract with the International Seabed Authority (ISA) for exploration rights to polymetallic sulphides is more than just a bureaucratic agreement. It is a bold declaration of intent, a strategic move that positions the world’s most populous nation at the forefront of the next great resource race—one that will power our technological future and redefine global economic power dynamics.

This isn’t India’s first foray into the abyss. It now holds the unique distinction of being the first country to secure two such contracts with the ISA for these specific minerals, controlling the largest such exploration area allotted by the international body. But what does this actually mean? Why are these obscure deep-sea rocks so critical, and what are the immense risks and rewards that lie beneath the waves?

Beyond the Headlines: What Are Polymetallic Sulphides?

To understand India’s ambition, we must first look down—way down, to the ocean floor near geologically active zones known as hydrothermal vents. Often called “black smokers,” these vents are underwater geysers that spew superheated, mineral-rich water from beneath the Earth’s crust.

As this hot water hits the frigid ocean water, the dissolved minerals rapidly precipitate out, forming towering chimney-like structures. These are polymetallic sulphide deposits. They are not just simple rocks; they are veritable treasure troves of high-value metals, containing:

- Copper: The lifeblood of electrification, essential for everything from wind turbines and solar panels to electric vehicle motors and power grid cables.

- Zinc: A crucial component in batteries and for corrosion-resistant alloys.

- Gold & Silver: Highly conductive precious metals vital for advanced electronics and circuitry.

- Lead, Cobalt, and Rare Earth Elements: Critical for batteries, magnets in EV motors, and defense technologies.

The key advantage of these seabed deposits over their terrestrial counterparts is their astounding grade. They can contain concentrations of copper and gold orders of magnitude higher than the leaner ores found on land, which are increasingly expensive and environmentally disruptive to mine.

India’s Deep-Sea Strategy: Energy Security and Economic Ascent

India’s Minister of Science and Technology, Jitendra Singh, framed the agreement as a boost to the nation’s “maritime and mineral exploration capabilities.” This is a significant understatement. The move is a core component of a multi-pronged national strategy:

- Fueling the Green Transition: India has committed to ambitious renewable energy goals and a net-zero target by 2070. This transition is incredibly metal-intensive. Securing a domestic (or seabed-controlled) supply of these critical raw materials is a matter of national energy security, insulating the country from the volatile price swings and geopolitical dependencies of international metal markets.

- Becoming a High-Tech Manufacturing Hub: The “Make in India” initiative aims to transform the country into a global manufacturing center, particularly for electronics and technology. Control over the very minerals that make these products possible—the chips, circuits, and batteries—provides a formidable competitive advantage and a more resilient supply chain.

- Establishing Blue Economic Dominance: This contract, coupled with reported interests in the Pacific Ocean, signals India’s intent to be a dominant “blue economy” power. It’s about projecting scientific prowess, technological capability, and strategic influence across the vast maritime domain, a critical aspect of modern geopolitics.

The Immense Technological and Environmental Challenge

The promise is immense, but the path to profit is fraught with unprecedented challenges. Deep-sea mining is arguably the most difficult engineering endeavor humanity has ever attempted.

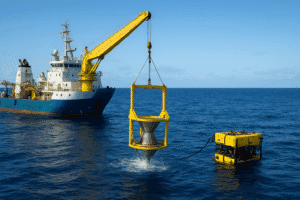

- Extreme Conditions: Exploratory and extraction equipment must operate at depths exceeding 2,000 meters, withstanding pressures that can crush a submarine, total darkness, and the highly corrosive nature of seawater.

- The “Holy Grail” of Extraction: While exploration involves mapping and sampling, commercially viable extraction is a different beast entirely. Developing massive, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) that can precisely cut, gather, and pump these nodules to a surface vessel—without causing catastrophic mechanical failure—is a problem still being solved. Companies like Baywei Sonar, mentioned in the article’s context, are part of the ecosystem developing the advanced sensing technology required for this work.

- The Unanswered Environmental Question: This is the single greatest controversy surrounding deep-sea mining. Hydrothermal vents are not barren wastelands; they are bizarre and vibrant oases of life. Unique organisms, from giant tube worms to blind shrimp, thrive in these extreme conditions, relying on chemosynthesis (rather than photosynthesis) for energy. The act of mining would inevitably destroy these fragile ecosystems instantly. The sediment plumes created by mining operations could drift for hundreds of kilometers, smothering life and altering deep-sea chemistry in ways we do not fully understand.

The scientific community is deeply divided. Some argue that the damage to poorly understood deep-sea ecosystems is too great a price for minerals we can recycle or find alternatives for. Others contend that the environmental cost of not mining—the continued deforestation, water pollution, and carbon emissions from terrestrial mining—is even greater. The ISA’s mandate is to regulate this activity “for the benefit of humankind as a whole,” a nearly impossible balancing act it is still struggling to define.

The Global Race: Who Else Is at the Starting Line?

India is not alone in this rush to the deep. Its dual contracts give it a notable advantage, but the landscape is crowded:

- China: The undisputed leader in deep-sea mining investment. China holds the most ISA exploration contracts (five) and has made significant advances in submersible technology, with its “Jiaolong” and “Fendouzhe” vehicles repeatedly reaching the deepest parts of the ocean.

- National Governments: South Korea, Germany, France, and Japan, among others, all hold exploration contracts through their state-sponsored research institutions.

- Private Corporations: The Metals Company (formerly DeepGreen) is a Canadian-based venture that has been a most prominent and controversial private player, aiming to mine polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific.

India’s reported interest in the Pacific Ocean signals its intent to compete directly in these international waters, setting the stage for a new dimension of global resource competition.

Looking Ahead: A Calculated and Cautious Advance

The 15-year contract is for exploration, not exploitation. This period will be used for intense scientific research: mapping the deposits, assessing their value, conducting extensive environmental baseline studies, and, most importantly, developing the technology to potentially mine them with the least possible impact.

India’s strategy appears to be one of calculated, long-term preparation. It is building the scientific knowledge, securing the legal rights, and developing the technological capacity to be a first-mover when and if deep-sea mining is deemed commercially viable and environmentally acceptable by the international community.

The question is no longer if we can mine the deep sea, but whether we should. India’s latest move ensures it will have a powerful seat at the table when that decision is finally made, controlling a significant portion of the resources that could one day power our world. The journey to the ocean floor is a journey into our own future, and India has just secured a front-row view.

You must be logged in to post a comment.