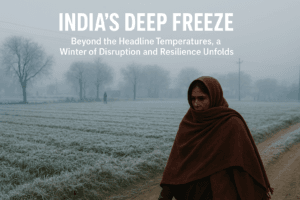

India’s Deep Freeze: Beyond the Headline Temperatures, a Winter of Disruption and Resilience Unfolds

North and Central India are experiencing an intense and unusually prolonged cold wave, with temperatures dipping to 2.3°C in Fatehpur and 1.8°C in parts of Madhya Pradesh, marking historic lows such as Bhopal’s longest cold spell in 84 years and Indore’s coldest night in 25 years. This severe chill is disrupting daily life, straining power grids, and stressing vulnerable populations, while also threatening key Rabi crops like mustard due to frost and reduced daytime warmth.

Urban centers are adapting through late starts, increased shelter use, and shifting economic activity, even as stark contrasts emerge within regions—like Rajasthan’s freezing east versus its warmer western districts. With forecasts predicting further cooling following Himalayan snowfall, this cold wave highlights India’s climatic extremes, agricultural vulnerabilities, and the need for stronger public health and climate-resilient systems.

India’s Deep Freeze: Beyond the Headline Temperatures, a Winter of Disruption and Resilience Unfolds

A shiver has descended, sharp and unrelenting, upon the vast plains of North and Central India. This isn’t merely a seasonal dip; it’s a pronounced cold wave, a climatic event that has woven itself into the fabric of daily life, agriculture, and public health. While headlines rightly spotlight the plunging mercury in Fatehpur (2.3°C) and parts of Madhya Pradesh (1.8°C), the real story lies in the silent, pervasive impact of this freeze—a tale of historical anomalies, vulnerable crops, urban adaptation, and the stark contrast between India’s regions.

The Grasp of the Cold: A Data-Driven Snapshot

The meteorological narrative is clear and chilling. In Rajasthan, the cold has found a firm foothold. Fatehpur’s 2.3°C is not an isolated figure but the apex of a trend seeing Sikar at 3°C and Jaipur, the bustling capital, dipping below 10°C for the first time this season to 9.2°C. The significance? It marks the arrival of intense winter at the doorstep of urban centers accustomed to milder beginnings.

Madhya Pradesh presents an even more dramatic picture. When Rewa, on the plains, records a lower minimum (5.8°C) than the hill station Pachmarhi, it signals an inversion and the depth of the cold air mass. The fact that 19 cities registered sub-10°C temperatures, with cold wave to severe cold wave conditions declared from Bhopal to Indore, underscores the event’s geographical spread.

Historical Context: This Isn’t Normal Winter

The India Meteorological Department’s (IMD) observations provide crucial context that elevates this from a cold snap to a notable climatic event. November 2024 was not just cool; it delivered “unusually prolonged cold.” Bhopal endured its longest cold wave spell in 84 years, a statistic that resonates with the weight of history. Indore experienced its coldest night in a quarter-century. This context is vital for public perception—it explains why this winter feels particularly harsh to residents and why authorities are on high alert. It’s a deviation from living memory, hinting at the volatile patterns modern climate systems can produce.

The Silent Crisis in the Fields: Frost on the Mustard Bloom

Beyond the urban chill lies the most vulnerable front: agriculture. Reports of frost in the mustard-growing belts near Alwar and other parts of Rajasthan are not mere weather notes; they are early warnings of economic distress. Mustard, a key Rabi (winter) crop, is in its flowering and pod-formation stage during this period. Frost, known as “pala” locally, is a deadly adversary. It can scorch flowers, damage pods, and drastically reduce yield. The sight of white frost on green fields is a farmer’s dread, translating to potential livelihood loss and upward pressure on edible oil prices nationally.

This agricultural anxiety is compounded by the dip in daytime maximums. When Sirohi’s high is only 22°C and other districts remain below 25°C, plant growth slows. Crops need a certain amount of daytime warmth for photosynthesis. A persistent combination of near-freezing nights and cool days stresses the plants, making them more susceptible to disease and reducing overall productivity. The IMD’s week-long cold wave alert for the Shekhawati region is, therefore, also an indirect advisory for thousands of farming families to take protective measures where possible.

Urban Life in a Chill: Adaptation and Strain

In cities like Bhopal, Indore, and Jaipur, the cold wave reshapes daily rhythms. Mornings begin later, as the advisory to limit exposure during early hours is heeded, especially by the elderly, homeless, and daily wage workers. Infrastructure is tested: peak power demand surges for heating, putting grids under strain. The social fabric reveals its threads—night shelters see increased occupancy, and charitable distributions of blankets and warm food become more critical.

The psychological impact is subtle but real. Prolonged grey skies and biting cold can affect mood and outdoor social activity. Business for street vendors, particularly those selling non-essential goods, often dips. Conversely, markets for winter wear, heaters, and hot food items see a boom. The urban experience of a cold wave is a complex dance between inconvenience, economic shift, and community response.

A Tale of Two Regions: The Rajasthan Paradox

The cold wave narrative within Rajasthan itself holds a fascinating paradox. While the east and north shiver, western Rajasthan—Barmer (30.2°C), Jaisalmer (28.4°C), Jodhpur (28.3°C)—experiences significantly warmer conditions. This stark 15-20 degree difference in daytime temperatures across a single state illustrates the diverse microclimates of India. It’s driven by geography: the cold, dry northwesterly winds affect the eastern parts more, while the western Thar Desert retains daytime heat. This contrast is a reminder that “North India” is not a monolith; local weather realities can be wildly different.

The Road Ahead: A Colder Phase Beckons

The forecast offers little respite. Western disturbances, typically associated with rainfall, are predicted to bring snowfall in the Himalayas around December 7-8. Counterintuitively for the plains, this often intensifies the cold wave. The snowfall reinforces the reservoir of cold air over the mountains, which then continues to drain southwards. The Bhopal and Raipur met centres’ warnings of a continuing downward trend suggest the coldest period may still be ahead.

Adding Value: Insights Beyond the Forecast

So, what genuine insight and value can be derived from this situation?

- Public Health Preparedness: This underscores the need for hyper-localized cold wave action plans, especially for vulnerable populations. It’s not just about issuing alerts but ensuring the logistics of shelter, healthcare for cold-related ailments, and public awareness are activated.

- Agricultural Risk Management: It highlights the gap between meteorological capability and on-ground agricultural advisory. Real-time SMS alerts about frost, coupled with simple mitigation techniques (like light irrigation or smoke pots), need to reach farmers faster.

- Climate Pattern Awareness: Events like Bhopal’s 84-year record cold spell invite reflection on climate variability. Are we seeing greater extremes—more intense heatwaves followed by sharper cold dips? Understanding this helps in long-term planning for infrastructure and agriculture.

- The Human Element of Resilience: Ultimately, the story is also one of adaptation. From the farmer checking his field at dawn to the chaiwallah seeing a longer queue, life adjusts. The cold wave, in its starkness, brings communities together, highlights inequalities, and tests systems.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Number

The temperature readings—2.3°C, 1.8°C—are vital data points, but they are only the beginning. The true narrative of this cold wave is etched in the worried lines on a farmer’s face, in the crowded night shelter, in the historical weather archives being consulted, and in the resilient pulse of cities slowing down but not stopping. As North and Central India brace for a colder phase, the event becomes a multifaceted lesson in climate impact, societal vulnerability, and the enduring human capacity to weather the storm, even when it comes as a silent, freezing wind.

You must be logged in to post a comment.