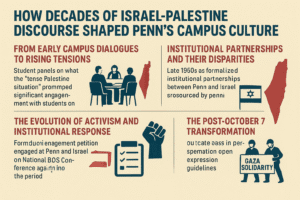

How Decades of Israel-Palestine Discourse Shaped Penn’s Campus Culture

For over seven decades, the Israel-Palestine conflict has evolved from an abstract topic of academic panels at the University of Pennsylvania into a defining and increasingly polarized force shaping campus identity, moving from early discussions around Israel’s founding in 1948 and contentious cultural exhibits in the 1960s to the rise of organized student activism, a significant institutional partnership with Israeli universities in the 1970s, and modern-era calls for divestment, which culminated in the transformative crisis following the October 7, 2023 attacks—a period that triggered a leadership exodus, congressional testimony, an encampment disbanded by police, and ultimately, the creation of new university policies and offices, reflecting the conflict’s profound and enduring impact on the institution’s culture, governance, and the very boundaries of free expression.

How Decades of Israel-Palestine Discourse Shaped Penn’s Campus Culture

An analysis of the University of Pennsylvania’s historical archives reveals that the Israel-Palestine conflict has evolved from academic discussions to a defining issue shaping institutional policies, campus culture, and the very boundaries of free expression at the Ivy League institution.

From Early Campus Dialogues to Rising Tensions

The founding of Israel in 1948 sparked some of Penn’s earliest campus engagements with the Middle East conflict. Student panels on what was then termed “the tense Palestine situation” prompted significant engagement, with students writing to members of Congress and attending events hosted by Penn Hillel to discuss politics in the new state.

The 1960s witnessed escalating tensions on campus, mirroring rising violence in the region. In 1966, an Arab World exhibit at Houston Hall labeled Israel as “Israeli-occupied territory of Palestine,” which then-Hillel director Samuel Berkowitz called “an affront to the Jewish community at the University.” At the same event, an Israeli display featured an “Arab Shepherd” showing an “unbathed figure tending to a flock of sickly sheep,” which Arab students said affronted their dignity. The Daily Pennsylvanian later described “an international shoving and shouting match in the West Lounge“.

The late 1960s saw the emergence of organized student activism around the issue. The first “Students for Israel” group appeared at Penn in 1969, followed a year later by Penn’s first recorded “Palestine Week,” sponsored by the Organization of Arab Students.

Institutional Partnerships and Their Disparities

The 1970s marked a period of formalized institutional partnerships between Penn and Israel. Following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, then-Penn President Martin Meyerson announced an exchange and research program with “the seven universities in Israel“. This program, resulting from two years of faculty work, led to substantial academic exchange throughout the 1970s, with Israeli professors teaching at Penn and Penn professors teaching at Israeli universities.

A significant disparity emerged in these international partnerships. While Penn-Israel programs flourished, a DP archival review found no evidence of Palestinian exchange programs during this period. Although Middle East Center director Thomas Naff traveled to Libya in 1978 to explore establishing “student training and research projects” with the Arab Development Board, no further record exists of this project’s development.

Campus debates during this era increasingly grappled with fundamental questions of legitimacy. In 1976, ads appeared in the DP offering transportation to protests at the United Nations as it voted on a resolution equating Zionism to racism. The following year, Hillel declined to participate in an Organization of Arab Students event debating whether Zionism was racist, with then-Hillel rabbi Michael Monson calling the Arab League speaker a “propagandist”.

The Evolution of Activism and Institutional Response

The turn of the millennium brought new dimensions to campus engagement with the conflict:

- 2002: Penn community members circulated the first divestment petition targeting defense corporations involved with Israel, garnering around 200 signatures. An anti-divestment petition received 8,000 signatures.

- 2012: The National Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Conference was held on Penn’s campus, prompting a surge in pro-Israel programming including lectures by Alan Dershowitz.

- 2010s: Pro-Palestinian activism on campus “significantly increased” according to archival analysis, aligning with growing sympathy for the Palestinian cause among young Americans.

Administrative responses throughout this period consistently emphasized free expression while rejecting divestment. Then-President Judith Rodin called divestment “much too blunt an instrument,” a position echoed by her successor Amy Gutmann.

The Post-October 7 Transformation

The Hamas attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, and Israel’s subsequent military response in Gaza marked a transformative period for Penn’s campus climate. The events triggered a chain reaction that would ultimately reshape university leadership and policies:

- Leadership Crisis: Wharton Board of Advisors Chair Marc Rowan publicly called for the resignation of President Liz Magill and Board Chair Scott Bok, encouraging alumni to terminate donations.

- Congressional Testimony: Magill’s testimony before the U.S. House Committee on Education and the Workforce, where she stated that qualifying calls for the genocide of Jews was “context-dependent,” prompted widespread condemnation and her resignation four days later.

- Encampment and Police Response: In April 2024, pro-Palestinian students erected a Gaza Solidarity Encampment on College Green. After 16 days of failed negotiations, Penn and Philadelphia police in riot gear disbanded the encampment, arresting 33 protesters including nine students.

The 2023-24 academic year witnessed unprecedented activism levels, with pro-Palestinian protests sweeping campus and sparking significant policy changes. The University implemented temporary open expression guidelines that directly addressed aspects of the encampment and other protests from that academic year.

Historical Parallels and Patterns

This evolution of discourse follows a recognizable pattern at Penn, reminiscent of earlier debates over the University’s relationship with Iran during the Shah’s regime. In the 1970s, Penn faced similar ethical questions regarding its affiliation with Pahlavi University, with some professors defending the relationship as potential leverage for change while others like faculty member Naomi Schneider compared it to “exchange programs with Nazi Germany“.

The continuity of certain themes across decades is striking—questions of institutional complicity, the ethics of academic partnerships, and balancing free expression with community safety have resurfaced repeatedly throughout Penn’s history with the Middle East.

The Current Landscape

In response to the heightened tensions, Penn has implemented several structural changes:

- Establishment of an Office of Religious and Ethnic Inclusion focused on Title VI compliance.

- Creation of Penn Global’s Middle East Distinguished Visiting Scholar Initiative.

- Adoption of a policy of institutional neutrality regarding local and world events not directly impacting the University.

The historical trajectory suggests that Israel-Palestine discourse at Penn has progressively intensified, moving from academic panels and cultural exhibits to encompassing institutional investments, governance structures, and the fundamental principles of campus expression. As interim President Larry Jameson noted during the encampment dispersal, the University proposed to “deploy Penn’s academic resources to support rebuilding and scholarly programs in Gaza, Israel, and other areas of the Middle East“.

This seven-decade evolution reflects both the changing nature of the conflict itself and broader shifts in how university communities engage with complex geopolitical issues—serving as a microcosm of the challenges facing higher education in navigating deeply polarized political landscapes while maintaining its educational mission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.