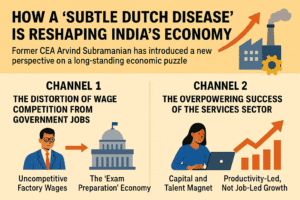

How a ‘Subtle Dutch Disease’ Is Reshaping India’s Economy

India’s historically underdeveloped manufacturing sector, despite rapid economic growth from 1980-2015, can be attributed to a “subtle Dutch disease,” as explained by former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian. Unlike the traditional model driven by natural resources, India’s version was caused by the twin successes of its high-skill services boom and its large, high-wage government sector, which distorted the labor market by making manufacturing jobs less attractive and profitable.

This effect was compounded by other factors, including low agricultural productivity, a restrictive regulatory environment that discouraged firms from scaling up, and the phenomenon of millions of potential workers staying out of the labor force to prepare for government exams. Consequently, this unique combination of factors created a powerful, reinforcing dynamic that pulled capital and labor away from factory jobs, leading to an incomplete structural transformation and a departure from the manufacturing-led development path seen in other Asian economies.

How a ‘Subtle Dutch Disease’ Is Reshaping India’s Economy

Former Chief Economic Advisor (CEA) Arvind Subramanian has introduced a compelling new perspective on a long-standing economic puzzle: why has India, despite rapid GDP growth, not experienced the massive shift from agriculture to manufacturing that propelled other developing nations? He attributes this to a “very subtle Dutch disease effect,” where the twin successes of a booming services sector and high-paying government jobs have inadvertently held back manufacturing growth .

This phenomenon, distinct from the traditional resource-based Dutch disease, offers a fresh framework for understanding the unique trajectory of India’s economic development.

The Core Argument: A Modern-Day Dutch Disease

The term “Dutch disease” originally describes a paradox where a boom in one sector (like natural resources) causes a country’s currency to appreciate, making its other exports (like manufactured goods) less competitive on the global market .

According to Subramanian, India is experiencing a subtle and homegrown version of this condition. The “boom” sectors are not oil or gas, but rather the high-skill services industry (like IT and finance) and the large government sector. Together, they have created a set of economic dynamics that have dampened the growth of labor-intensive manufacturing .

The Two Channels of India’s Economic Distortion

Subramanian’s analysis points to two powerful, reinforcing channels through which this effect operates.

Channel 1: The Distortion of Wage Competition from Government Jobs

The government is a major employer in India, and its compensation packages, especially at the lower end of the skill spectrum, are disproportionately high compared to the private manufacturing sector. This creates a critical distortion in the labor market .

- Uncompetitive Factory Wages: For a worker considering a job in a factory, the attractive wages and job security of a government position become the competing benchmark. This makes relatively lower-wage manufacturing jobs less appealing, constricting the supply of low-skill labor to factories .

- The “Exam Preparation” Economy: Millions of young Indians spend years outside the active labor force, preparing for civil service and other government exams. This further reduces the available labor pool for manufacturing and represents a significant opportunity cost for the industrial sector .

Channel 2: The Overpowering Success of the Services Sector

India’s services sector is a powerhouse, contributing an estimated 55% of the country’s Gross Value Added (GVA) . Its success has drawn in capital, entrepreneurship, and high-skill talent, creating a gravitational pull away from other areas.

- Capital and Talent Magnet: The rapid growth in high-value domains like information technology (IT), financial intermediation, and professional consulting has pulled investment and India’s best-educated workforce away from industrial ventures .

- Productivity-Led, Not Job-Led Growth: The services sector’s expansion is increasingly capital- and technology-intensive. While it drives national output, it has not generated employment at the same scale. It accounts for about 55% of GVA but only 29.7% of India’s workforce, highlighting a stark output-employment gap . This limits the sector’s ability to absorb large numbers of workers moving out of agriculture.

The Broader Economic Context: Other Contributing Factors

Subramanian places this “Dutch disease” within a wider context of historical and structural challenges that have also hampered manufacturing growth :

- Historical Policy Constraints: India’s initial decades of economic policy, marked by protectionism and a stifled private sector, resulted in low growth and a very small manufacturing base to begin with.

- The Agricultural Productivity Gap: Unlike Japan, Korea, or China, India did not experience a dramatic surge in agricultural productivity. This limited the generation of rural incomes and surpluses that could have created demand for locally manufactured goods.

- The Regulatory Environment: A regulatory landscape, often summarized by the phrase “midgets making widgets,” has discouraged firms from achieving larger, more efficient scales of operation.

The Current Economic Landscape and Manufacturing Initiatives

Despite these historical headwinds, India’s economy is demonstrating remarkable strength. Recent data for fiscal year 2025-26 shows robust GDP growth of 8% in the first half (April-September), driven by strong performances in both the secondary (7.6%) and tertiary (9.3%) sectors .

The government is actively pushing to bolster manufacturing through flagship programs like the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme. This initiative, covering 14 strategic sectors, has already attracted investments of over ₹1.76 lakh crore and is designed to boost domestic manufacturing, exports, and job creation .

However, manufacturing growth faces contemporary challenges, including new labour codes that are anticipated to increase manpower costs for companies by 5-15% across sectors. While beneficial for workers, this could present short-term adjustment hurdles for firms, particularly in labor-intensive industries and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) .

Conclusion: Rethinking the Path to Development

Arvind Subramanian’s “subtle Dutch disease” theory provides a powerful and nuanced explanation for India’s unconventional economic evolution. It suggests that the country’s path was not merely hindered by failures in industrial policy but also shaped, paradoxically, by the success of its services and public sectors.

This analysis implies that policy solutions need to be equally nuanced. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, fostering a more robust manufacturing sector may require targeted strategies that account for these unique labor market distortions and work towards creating a more balanced and synergistic growth model for India’s future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.