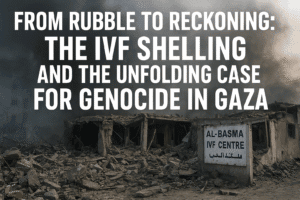

From Rubble to Reckoning: The IVF Shelling and the Unfolding Case for Genocide in Gaza

Based on her UN Commission’s investigation, former South African judge and international jurist Navi Pillay concludes Israel has committed genocide in Gaza, a finding she argues is evidenced by specific, intentional acts like the shelling of a standalone IVF clinic that destroyed 4,000 embryos—an act aimed at preventing Palestinian births.

Pillay, drawing parallels to the rhetoric that fueled the Rwandan genocide, asserts that this real-time crisis, witnessed globally, places a legal obligation on all states to intervene, and she condemns the international community’s inaction as complicity, while finding hope for justice in the power of collective public solidarity, much like the movement that helped end South African apartheid.

From Rubble to Reckoning: The IVF Shelling and the Unfolding Case for Genocide in Gaza

The language of international law is often cold, a lexicon of clauses and conventions designed to codify humanity’s worst instincts into manageable, prosecutable categories. But sometimes, a single image, a solitary act of destruction, can cut through the legalese and lay bare the raw, human truth of a crime. For Navi Pillay, a jurist who has spent a lifetime confronting atrocity, that image is not of a bombed tower block or a ravaged village, but of a quiet, clinical space: the Al-Basma IVF Centre in Gaza, struck by a single, precise Israeli shell in December 2023.

The result was the instantaneous annihilation of 4,000 embryos.

This was not collateral damage in a dense urban battlefield. As Pillay, the former chair of the UN’s Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, methodically explains, the clinic stood alone, separate from hospital buildings. If the stated Israeli justification for striking medical facilities is the presence of Hamas, why target this solitary building housing nitrogen tanks? To Pillay, the answer is chillingly clear: this was an act “intended to prevent births” among Palestinians. It is, she argues, a signal example in a vast and terrible mosaic of evidence that has led her to a weighty and damning conclusion: Israel is committing genocide in Gaza.

The Burden of Witnessing: A Crime in Real Time

Pillay is no starry-eyed activist. She is a legal pioneer—the first non-white woman to practice law in Natal, South Africa, a former judge on the International Criminal Court, and a presiding judge at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. She has navigated the aftermath of mass slaughter and institutionalized racism. When she uses the word “genocide,” she does so with the full weight of that experience and a profound understanding of the legal threshold required.

“We did our own investigations for over two years,” she states, her tone one of unassailable conviction. “There’s nothing we put in our report that we didn’t personally verify.” Her commission operated like a court of law, she explains, sifting through evidence, cross-referencing testimony, and building a case they believe is irrefutable until a formal ruling from the International Court of Justice.

What makes this genocide so profoundly unusual, and so uniquely agonizing, Pillay suggests, is that it is not a historical tragedy being pieced together from archives and mass graves. “We are all witnesses to it,” she says. “It’s happening in real time. We see it on our screens every day.” This is a genocide livestreamed, a horror unfolding in the palm of our hands, making global inaction not just a policy failure but a form of collective, passive complicity.

The Echoes of History: From “Cockroaches” to “Human Animals”

Drawing from her experience with the Rwandan genocide, Pillay identifies a sinister and familiar pattern in the rhetoric of political leaders. In Rwanda, the Tutsi were systematically dehumanized as “inyenzi” — cockroaches — to be “exterminated.” This language provided the ideological fuel for the machetes.

She hears a haunting echo in the statements of Israeli leaders. She points specifically to then-Defence Minister Yoav Gallant’s declaration of a “complete siege” on Gaza in October 2023, alongside his description of the people there as “human animals.”

“The idea comes from the politicians to destroy this group in all or in part,” Pillay states, drawing a direct line from the incendiary language of dehumanization to the brutal logic of genocide on the ground. This verbal violence, she argues, is not mere political posturing; it is a precursor and a permission slip for physical violence on an apocalyptic scale. The shell that destroyed 4,000 embryos was, in this light, not an anomaly but a manifestation of a stated intent to destroy the future of a people.

The Architecture of Impunity: Why Do States Look Away?

If the evidence is so clear and the legal authority of the commission so established, why has the international response been so tepid? Pillay turns from the language of evidence to the language of legal obligation. “It is the responsibility of all states,” she insists. “They have a legal obligation to stop the commission of genocide, to prevent it, and to protect against it happening.”

The prohibition on genocide, she reminds us, is absolute. There are no exceptions for self-defence or military necessity that can justify it. Yet, powerful nations have largely responded with hand-wringing and cautious diplomacy, failing to take the concrete, coercive measures that international law demands in the face of such a crime. This inaction, in Pillay’s view, is a betrayal of the post-Holocaust promise of “Never Again” and a corrosion of the entire framework of international justice.

“Why have states not responded to this legal obligation?” she asks, a note of frustration palpable. The silence of governments, however, stands in stark contrast to the awareness of the global public. People tell her, “Why are you reporting this genocide now? We know this, we are all witnesses.”

The Long Road from Apartheid: Finding Hope in Collective Action

Pillay’s perspective is uniquely informed by her own life under, and struggle against, South African apartheid. She recalls the profound humiliation of a system that rendered her four degrees meaningless in the face of her skin colour. “I was a lawyer. I had four degrees, but I was treated like dirt,” she says, the memory still vivid.

Yet, from that place of oppression, she draws a powerful and hopeful parallel. “I never thought apartheid would end in my lifetime,” she confesses. But what sustained the liberation struggle was not the certainty of victory, but the power of collective, global solidarity.

She recalls, with palpable warmth, the distant protests that gave her and her comrades strength—the Australian students demonstrating against the all-white Springboks rugby tour, the families in other nations boycotting South African goods. “I remember we somehow saw pictures… it must have seemed such a small thing. Would it really help end this huge monstrosity of apartheid if we stopped playing this all-white team? Yes, it does: the smallest act, that’s what gave us strength.”

This history is a lesson for the present. The fight for justice in Palestine, she implies, will not be won in diplomatic chambers alone, but through the relentless, cumulative pressure of global civil society—the protests, the boycotts, the millions of small acts of conscience that, together, can achieve the seemingly impossible.

Beyond the Ceasefire: The Non-Negotiable Path to a Just Peace

Pillay welcomes the current, fragile truce in Gaza as a necessary respite from the bloodshed, but she is under no illusions that it constitutes a peace. A true and lasting resolution, she argues, must address the root cause of the conflict: the decades-long occupation and the denial of Palestinian self-determination.

Crucially, she states, any negotiation that excludes the principal stakeholders is doomed to fail. “Palestinians have a right to self-determination. They know how to govern themselves. I wouldn’t even say they should be consulted: no, they should have the leading role here. The people for whom this matters most must be at the table.”

And for any peace to be durable, it cannot be built on a foundation of impunity. “People want justice and accountability,” Pillay asserts, “and justice has to be universal to succeed.” There must be a reckoning for the crimes committed by all parties, a process that acknowledges the profound suffering inflicted and establishes a truthful historical record.

The 4,000 embryos lost in that single, targeted shell are more than a statistic; they are a metaphor for a future denied. Navi Pillay’s work, culminating in the painful but necessary finding of genocide, is an attempt to force the world to look squarely at that denied future and to recognize its own responsibility in allowing it to be shattered. The shells may have stopped falling for now, but the reckoning, she insists, has only just begun. The witnesses are watching, and history, with Pillay as one of its most formidable scribes, is taking notes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.