Confession in New York: What Nikhil Gupta’s Guilty Plea Means for Vikash Yadav’s Future

Nikhil Gupta’s guilty plea in a New York court has transformed the US case against former R&AW officer Vikash Yadav from allegations into judicially confirmed facts, as Gupta admitted to working at the direction of an Indian government official (identified as Yadav) in a murder-for-hire plot against American citizen Gurpatwant Singh Pannun. Yadav now faces a federal arrest warrant and Interpol Red Notice, effectively confining him to India, while Gupta’s potential cooperation with prosecutors could provide direct evidence linking Yadav to the conspiracy. Although the US can theoretically seek Yadav’s extradition under the 1997 treaty, India is unlikely to hand over a former intelligence official and may instead pursue domestic prosecution on separate extortion charges—a diplomatic compromise that would satisfy American demands for accountability while maintaining Indian sovereignty.

Confession in New York: What Nikhil Gupta’s Guilty Plea Means for Vikash Yadav’s Future

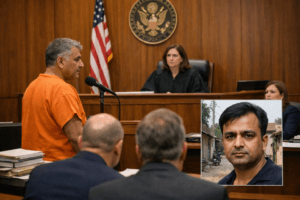

The February morning in New York’s Southern District courtroom was unremarkable by federal standards—fluorescent lights, polished wood, the quiet rustle of legal documents. But when Nikhil Gupta spoke his guilty plea into the record, the reverberations crossed nine time zones and landed in a narrow lane in Pranpura, Haryana, where a former Indian intelligence officer now lives under circumstances he likely never anticipated.

Gupta’s admission before Judge Jennifer H. Parker wasn’t merely a legal formality. It transformed what had been a collection of allegations into something far more dangerous for Vikash Yadav: judicially confirmed fact.

The Shift from Allegation to Admission

For nearly two years, the case against Yadav existed in a peculiar legal limbo. The US Department of Justice had named him as “CC-1″—a senior field officer with India’s Research and Analysis Wing who allegedly directed a murder-for-hire plot against Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, a American citizen and Sikh separatist leader. But an indictment, no matter how detailed, remains just an accusation until tested in court.

Gupta’s guilty plea changed that equation entirely.

“When a co-conspirator pleads guilty, they’re not just admitting their own involvement,” explains Sarah Chen, a former federal prosecutor who handled international conspiracy cases in Manhattan. “They’re essentially confirming to the court that the conspiracy existed, that it operated in the manner described, and that the individuals named in the indictment were part of it. For prosecutors, this is invaluable.”

The court documents leave little ambiguity about Gupta’s role. He admitted to working “at the direction of an Indian government employee”—the same individual federal prosecutors have since identified as Yadav. The $15,000 advance payment Gupta acknowledged making to what he believed was a hitman (actually an undercover DEA operative) now serves as concrete evidence of the plot’s operational reality.

A Fugitive’s New Reality

Yadav’s current legal status presents a study in contrasts. In the formal architecture of American justice, he remains a wanted fugitive—subject to a federal arrest warrant issued by the Southern District of New York in October 2024, his name and photograph displayed on the FBI’s “Most Wanted” list alongside international drug traffickers and terrorism suspects.

Yet in practical terms, he continues to live in India, moving through a country that has not arrested him and shows no signs of doing so. This disconnect between legal theory and political reality defines the strange half-life he now occupies.

The Interpol Red Notice issued at Washington’s request compounds his predicament. Those notices function as international wanted posters, alerting law enforcement in 196 member countries that an individual is sought for extradition. For Yadav, this means any international travel carries extraordinary risk. A connecting flight through Frankfurt, a speaking engagement in London, even a family vacation to Dubai could trigger an arrest and eventual transfer to New York.

“The Red Notice creates a cordon around him,” says international law expert Michael Torres. “He’s effectively confined to India and perhaps a handful of countries that either lack extradition treaties with the US or maintain sufficiently strained relations that they’d ignore the notice. But the comfortable assumption that he can move freely ended the moment that notice was published.”

The Cooperation Question

Perhaps the most significant unknown in this evolving legal drama centers on what Gupta told prosecutors before entering his plea. In the federal system, guilty pleas often precede cooperation agreements—defendants provide testimony or evidence against others in exchange for reduced sentences.

Gupta’s sentencing is scheduled for May 29. The gap between plea and sentencing is deliberate, allowing prosecutors to evaluate the usefulness of any information provided. If Gupta has shared encrypted communications, detailed the chain of command, or offered testimony directly linking Yadav to the plot, the US government now possesses evidence that would make a future trial against Yadav considerably more straightforward.

“Co-conspirator testimony is among the most powerful tools prosecutors have,” notes Chen. “It’s someone from inside the operation explaining how things actually worked, who gave orders, who knew what. When that testimony comes with corroborating evidence—messages, financial records, travel documents—it becomes extremely difficult to counter.”

The US Department of Justice has remained silent about whether Gupta’s plea includes a cooperation component, a standard practice designed to protect ongoing investigations and the safety of cooperating witnesses. But experienced observers note that the timing and circumstances suggest more than a simple admission of guilt.

Extradition: The Legal Framework

Should the United States formally request Yadav’s extradition—a step that becomes more likely following Gupta’s plea—the legal pathway exists, though political obstacles loom large.

The 1997 US-India Extradition Treaty establishes the framework for such requests. Article 9 requires the requesting nation to provide sufficient information to establish probable cause that the individual committed the alleged crimes. Gupta’s admission of the $15,000 payment, combined with his testimony about Yadav’s direction of the plot, would easily satisfy this standard.

The treaty’s exceptions, however, provide potential escape routes. Article 3 allows refusal if the offense is deemed “political in character.” India might attempt to characterize the Pannun plot as related to national security concerns about Sikh separatist movements. But murder-for-hire prosecutions in the United States rarely qualify for the political offense exception, which typically applies to crimes like sedition or treason directly tied to political expression.

More practically, India could invoke Article 6, which permits denial of extradition if the person is being tried or punished in India for the same offense. This creates an intriguing possibility: by prosecuting Yadav domestically, New Delhi could honor the technical requirements of the treaty while ensuring he never faces an American courtroom.

The Domestic Prosecution Option

Reports from January 2025 indicated that an Indian inquiry committee recommended legal action against Yadav in connection with separate criminal matters. Delhi Police subsequently registered an extortion case against him, providing the foundation for domestic prosecution.

This approach carries certain advantages for Indian authorities. It demonstrates responsiveness to American concerns while maintaining sovereign control over a former intelligence officer. It avoids the politically explosive prospect of handing over an RAW official to foreign prosecution. And it potentially satisfies the treaty’s double jeopardy protections, making extradition requests deniable on technical grounds.

“Keeping Yadav in Indian custody on domestic charges would be the cleanest solution from New Delhi’s perspective,” suggests political analyst Rohit Mehra. “The United States gets to see him face consequences. India maintains its sovereignty. Yadav doesn’t end up in a federal prison in Pennsylvania. It’s the diplomatic equivalent of a face-saving compromise.”

Whether American prosecutors would accept this outcome remains uncertain. The charges Yadav faces in the United States—murder-for-hire, conspiracy to commit murder-for-hire, money laundering conspiracy—carry potential sentences far exceeding anything India might impose for extortion. US officials may insist that justice requires his presence in an American courtroom.

Sovereign Immunity and Official Capacity

India’s communication to the United States that Yadav “is no longer employed by the Government of India” carries legal significance beyond its face value. By severing his official status, New Delhi removed the most potent defense Yadav might have raised against prosecution.

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act generally protects foreign states and their agencies from US jurisdiction. But the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Samantar v. Yousuf clarified that individual officials do not enjoy the same protection for acts outside their official capacity or for violations of international law. A former official, stripped of government status, possesses even fewer immunity claims.

This matters because Yadav’s defense, had he been arrested while still employed, might have centered on the argument that his actions constituted official intelligence activities rather than criminal conspiracy. By confirming his departure from government service, India essentially conceded that any prosecution would proceed against him as a private individual, not as a representative of the Indian state.

The Human Dimensions

Lost in the legal analysis and diplomatic maneuvering is the human reality of Yadav’s situation. Photographs show a narrow lane near his home in Haryana’s Pranpura—unremarkable, ordinary, the kind of street where neighbors know each other and children play in the evening dust. It is not where someone expects to live after their face appears on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.

The psychological toll of such status defies easy calculation. Every knock on the door carries different weight. Every unfamiliar vehicle on the street prompts assessment. The knowledge that Interpol circulates your photograph to law enforcement agencies worldwide transforms ordinary life into something resembling witness protection in reverse—not hidden, but hunted.

For Yadav’s family, the situation presents its own cruelties. Children who may not understand why their father cannot travel, why journalists occasionally appear, why the comfortable assumptions of middle-class Indian life have curdled into something constrained and cautious. Spouses who must navigate the gap between private knowledge of a loved one and public perception of a wanted fugitive.

These human dimensions rarely appear in Justice Department press releases or diplomatic notes, but they shape the reality of what Gupta’s guilty plea means in practical terms.

What Comes Next

The immediate future holds several potential developments. Gupta’s May 29 sentencing will provide the first clear indication of whether his cooperation proved valuable to prosecutors. A significant sentence reduction would suggest he provided substantial assistance. The standard range for his charges extends to life in prison, though cooperation often produces dramatically lower terms.

If prosecutors believe they have sufficient evidence for Yadav’s prosecution, they may intensify diplomatic pressure for his transfer. This could take the form of formal extradition requests, elevated discussions between Justice Department officials and Indian counterparts, or even public statements designed to maintain political attention on the case.

India’s response will likely balance multiple considerations: the desire to maintain strong intelligence and security relationships with the United States, domestic political sensitivities about handing over an official, and the practical reality that Yadav now represents a complicating factor in bilateral relations.

The most probable outcome involves some form of Indian prosecution that satisfies American demands for accountability while avoiding extradition. Whether this proves acceptable to US officials depends on the severity of charges India brings, the vigor with which it pursues them, and the sentences ultimately imposed.

The Broader Implications

Beyond Yadav’s personal circumstances, Gupta’s guilty plea carries implications for US-India intelligence relationships that extend far beyond this single case. The indictment and conviction of an RAW official in American courts would establish precedent that intelligence officers are not immune from prosecution for activities that violate US law—a principle with significance for both nations’ operations worldwide.

For Indian intelligence, the case suggests that operational security failures can expose officers to extraordinary legal jeopardy. The use of a middleman like Gupta, who ultimately cooperated with American authorities, created vulnerabilities that traditional tradecraft is designed to prevent. Future operations will likely reflect these lessons, with greater emphasis on compartmentalization and reduced reliance on non-official covers.

For American authorities, the successful prosecution demonstrates the reach of US law enforcement even when the primary targets remain beyond physical custody. The combination of conspiracy charges, cooperative witnesses, and international pressure creates accountability mechanisms that function even without extradition.

Conclusion

Nikhil Gupta’s guilty plea in a New York courtroom transforms an indictment into an admission, allegations into evidence. For Vikash Yadav, this shift carries consequences that will define the remainder of his life regardless of whether he ever sets foot in the United States.

He exists now in a peculiar category—charged but not captured, named but not convicted, constrained by international warrants while living in his home country. The lane in Pranpura where photographs show his residence has become something between sanctuary and prison, a place where he remains free but cannot freely leave.

The May sentencing of his co-conspirator will provide the next chapter in this ongoing legal drama. Whether it leads toward extradition, domestic prosecution, or continued stalemate depends on calculations being made in Washington and New Delhi—decisions that balance justice, sovereignty, and the complicated relationship between two nations that remain partners despite this extraordinary breach.

For Yadav, those distant deliberations will determine whether his future holds American courtrooms or Indian confinement, whether his name becomes a footnote in diplomatic history or a precedent in international law. The guilty plea in New York ensured that the question would be asked. The coming months will determine the answer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.