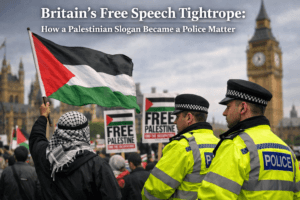

Britain’s Free Speech Tightrope: How a Palestinian Slogan Became a Police Matter

In December 2025, following terrorist attacks in Manchester and Sydney, the UK’s Metropolitan Police and Greater Manchester Police announced a decisive shift in policy, stating they would arrest anyone chanting or displaying the slogan “globalise the intifada” at protests. The policy was enforced hours later with five arrests at a London demonstration, sparking intense national debate. Pro-Palestinian groups, like the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, condemned the move as political repression, arguing “intifada” is a legitimate term of resistance, while Jewish community organizations welcomed it as a necessary step against incitement, perceiving the chant as a direct call for violence.

This action forces a legal reckoning, placing the question of whether such speech constitutes a hate crime before the courts and testing the balance between free speech and public safety in a climate of heightened fear and polarization.

Britain’s Free Speech Tightrope: How a Palestinian Slogan Became a Police Matter

The words we chant on the street and the laws we write in parliament exist in constant tension—a balance between expression and safety that shifts with the times and trembles with each new tragedy.

In the wake of a horrific terror attack in Sydney and mounting fear within British Jewish communities, two of the United Kingdom’s largest police forces have fundamentally altered their approach to protest policing. On December 17, 2025, the Metropolitan Police and Greater Manchester Police announced they would now arrest anyone chanting or displaying the slogan “globalise the intifada” at demonstrations. Within hours, this new policy was tested and enforced, leading to multiple arrests at a pro-Palestinian protest in London. This decisive move has ignited a fierce national debate, placing the UK at the center of a global struggle to define the boundaries between free speech, public safety, and hateful incitement.

The Announcement: A “Recalibration” in Policing

The change was announced in a rare joint statement from Sir Mark Rowley, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and Sir Stephen Watson, Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police. Their language was stark and unambiguous. They stated that while prosecutors had previously advised that many contentious phrases “don’t meet prosecution thresholds,” the context had now changed.

“Violent acts have taken place, the context has changed – words have meaning and consequence. We will act decisively and make arrests,” the statement read.

The “violent acts” cited were two specific terrorist attacks: the October 2025 knife attack at the Heaton Park Hebrew Congregation Synagogue in Manchester, which killed two people, and the December 2025 mass shooting at a Hanukkah celebration on Bondi Beach in Sydney, Australia, which killed fifteen. The police chiefs argued these events, part of a documented surge in antisemitic hate crime, necessitated a “more assertive” and “enhanced approach”. Frontline officers were immediately briefed, and the forces pledged to use Public Order Act powers to impose conditions around London synagogues during services.

Immediate Enforcement and Community Reaction

The policy was not theoretical. That same evening, police detained five individuals at a protest outside the Ministry of Justice in Westminster, London. Two were arrested specifically “for racially aggravated public order offences” related to allegedly shouting slogans “involving calls for intifada”. The swift enforcement demonstrated the seriousness of the new directive.

The reaction from Britain’s communities was immediate and deeply polarized, reflecting the profound divisions the policy seeks to navigate.

| Group/Individual | Position | Key Argument |

| UK Chief Rabbi, Ephraim Mirvis | Supportive | Called it “an important step towards challenging the hateful rhetoric… which has inspired acts of violence and terror”. |

| Board of Deputies of British Jews | Supportive | Welcomed the “necessary intervention,” stating they had long warned the slogan incited violence. |

| Campaign Against Antisemitism (Gideon Falter) | Critical Support | Said banning one chant was a “useless token measure” and that police were “only now waking up” after two years of inaction. |

| Palestine Solidarity Campaign (Ben Jamal) | Opposed | Condemned it as “political repression of protest for Palestinian rights,” arguing “intifada” is not a call for violence but for “shaking off” injustice. |

| Jewish Voice for Liberation | Opposed | Argued it was an inappropriate response and that they had “very rarely, if ever” encountered antisemitism at protests. |

The Core of the Controversy: Law, Language, and Intent

At the heart of this clash lies a fundamental legal and semantic conflict. The Arabic word “intifada” literally translates to “uprising,” “resistance,” or “shaking off”. For Palestinians and their supporters, it is a historical term of liberation, referencing primarily non-violent civil disobedience during the First Intifada (1987-1993) against Israeli occupation. For many in Jewish communities, however, the term is inextricably linked to the Second Intifada (2000-2005), which was marked by suicide bombings and attacks that killed approximately 1,000 Israelis. To them, especially when paired with the word “globalise,” it is perceived as a direct call to export violent terrorism to Jewish communities worldwide.

This divergence in interpretation creates a significant legal gray area. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), which decides whether to bring charges in England and Wales, had consistently advised police that such phrases often did not meet the high threshold for prosecution under hate speech or public order laws. The new police policy openly challenges that advisory stance.

Legal commentator Joshua Rozenberg highlighted this tension, noting the police chiefs are essentially choosing to “test the proposition” in court. By making arrests, they force the CPS and the judiciary to make a definitive ruling on whether “globalise the intifada” constitutes a racially aggravated public order offence in the current climate. As one police source stated, “We get all the flak for it. The community only see the inaction. It’s not realistic we change nothing and keep plugging on with the same approach”.

A Climate of Fear: The Context Behind the Crackdown

The police “recalibration” did not occur in a vacuum. It was a response to what community leaders describe as an unprecedented and palpable atmosphere of fear. The terrorist attacks in Manchester and Sydney were catastrophic peaks in a rising tide of antisemitic incidents.

In Birmingham, for example, Jewish students shared harrowing accounts of being followed, chased, and screamed at with epithets like “dirty Jews”. One student stated, “I’d much rather be [in Israel] in a bomb shelter, as I have been, than here in Birmingham”. A synagogue in the region received an answerphone message threatening to hunt members and “blow their heads off”.

Nationally, the Community Security Trust (CST) recorded 1,521 antisemitic incidents in the first half of 2025 alone, a figure “fuelled by ongoing reactions to the conflict in the Middle East”. This tangible deterioration in community safety provided the compelling context police cited for their more interventionist stance.

International Echoes and Diverging Paths

The attack in Sydney that partly prompted the UK’s policy shift led to a different governmental response in Australia. While UK authorities focused on protest chants, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced moves toward tougher gun control laws, noting the attackers used legally owned firearms. The Premier of New South Wales, Chris Minns, considered reforms to deny protest permits after terrorist events, worrying about “combustible” community tensions.

This trans-national contrast underscores a broader debate: whether to address the symptoms of extremism (like hateful speech at protests) or what are perceived as its enabling factors (like weapon access). The UK’s choice has placed it in a delicate diplomatic position, with Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar having previously urged both Australia and Britain to act against the “surge” of antisemitism.

The Road Ahead: Protest, Prosecution, and Principle

The immediate aftermath of the policy announcement reveals the practical and philosophical challenges ahead.

- The Enforcement Dilemma: As Gideon Falter of the Campaign Against Antisemitism skeptically asked, how will police enforce a ban on one specific chant within the cacophony of a large protest?. This raises questions about selective policing and the potential for confrontational escalations during arrests.

- The Slippery Slope Concern: Pro-Palestinian campaigners warn this is a dangerous precedent. Ben Jamal of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign pointed out that some groups have also argued that chants like “Free, free Palestine” or calls for a boycott of Israel should be considered antisemitic. They fear a gradual narrowing of permissible speech.

- The Legal Reckoning: All eyes will now be on the Crown Prosecution Service. Will it prosecute the arrested individuals? Lionel Idan, the CPS hate crime lead, gave a non-committal response, stating the service would “carefully consider each case” to see if it meets the threshold. The courts’ decisions will either legitimize the police’s assertive stance or reveal it as an operational overreach.

- The National Ripple Effect: Currently, the policy applies only to London and Greater Manchester. Its success or failure will likely determine whether other UK police forces adopt similar measures, potentially creating a patchwork of protest regulations across the country.

The British government has signaled sympathy for a tougher line. Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who denounced the Sydney attack as “sickening,” simultaneously announced increased funding for Jewish community security and ordered a review of protest and hate crime laws.

The decision to arrest individuals for chanting “globalise the intifada” is more than a change in police tactics. It is a societal stress test. It probes the resilience of Britain’s liberal democratic traditions—the right to assemble and speak freely—under the intense pressure of communal fear and transnational violence. The police have thrown the question into the lap of the judiciary: in today’s Britain, where is the line between a political slogan and a threat of violence?

The answer will determine not only the future of protest in the UK but will also contribute to a global conversation about how democracies can protect themselves from hatred without sacrificing the fundamental freedoms that define them. As Sir Stephen Watson of Greater Manchester Police framed it, the state faces “a significant threat, not just to our Jewish communities, but to our country”. How it chooses to counter that threat will write a defining chapter in the story of 21st-century civil liberties.

You must be logged in to post a comment.