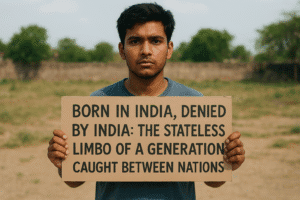

Born in India, Denied by India: The Stateless Limbo of a Generation Caught Between Nations

Bahison Ravindran, a 34-year-old man born in India to Sri Lankan Tamil refugee parents, is fighting for citizenship after being declared stateless and arrested for possessing an Indian passport obtained under the belief he was a citizen by birth. His case highlights a systemic issue affecting thousands born in India after a 1987 legal amendment requiring at least one Indian parent for automatic citizenship, a rule unknown to many.

Despite a life built in India, Ravindran and over 22,000 others like him remain in legal limbo because India is not a signatory to international refugee conventions and its 2019 citizenship law excludes Sri Lankan Tamils, leaving this India-born generation without a nationality and pinning their hopes on judicial intervention for recognition.

Born in India, Denied by India: The Stateless Limbo of a Generation Caught Between Nations

The concept of citizenship is, for most, a simple fact of existence—as inherent as a birthplace or a mother tongue. It’s the invisible thread connecting an individual to a state, granting rights, imposing duties, and offering an identity. For 34-year-old Bahison Ravindran, that thread has been severed, leaving him in a terrifying legal vacuum. His story is not just a personal tragedy but a stark indictment of a systemic failure affecting thousands born on Indian soil yet considered citizens of nowhere.

Bahison Ravindran did everything right. He studied, built a career as a web developer, paid taxes, and carried an Indian passport. He voted, he worked, he lived. By every measure of daily life, he was Indian. The rude awakening came not from a sudden discovery of a hidden past, but from the cold, hard letter of a law he never knew applied to him. In April, the Indian state he called home arrested him, declaring his passport invalid and his citizenship non-existent. The crime? Being born to the wrong parents in the right country.

The Legal Labyrinth: A Birthright Rescinded

The crux of Ravindran’s predicament lies in a pivotal, yet little-known, amendment to India’s citizenship law. For decades, the principle of jus soli, or “right of the soil,” prevailed. Being born in India made you Indian. However, the Citizenship Act of 1955 was amended in 1986 and 1987, largely in response to fears of illegal migration from Bangladesh.

The new rule was stark: for any child born on or after July 1, 1987, to acquire Indian citizenship by birth, at least one parent must be an Indian citizen at the time of the birth. Bahison Ravindran was born in 1991 in Tamil Nadu. His parents were Sri Lankan Tamils who had fled the brutal civil war in their homeland just months before, seeking refuge in a land that shared their language and culture. They were registered refugees, but under Indian law, they remained Sri Lankan citizens. By a legal technicality, their son, born on Indian soil, was stateless from his first breath.

This legal nuance remained buried in statute books, unknown to thousands of families simply trying to survive. Ravindran’s case reveals a catastrophic communication gap between the state and the people it hosts. He obtained a passport, a document most consider definitive proof of citizenship, not once, but twice. Each issuance involved layers of verification by local police and central authorities. At no point was the flaw in his status detected. “In all these years, no-one ever told me I was not Indian,” he told the BBC. This points not to malice on his part, but to a system that failed in its duty of care until it was time to punish.

A Legacy of Conflict, A Life in Limbo

To understand Ravindran’s story is to understand the plight of Sri Lankan Tamil refugees in India. The exodus began in the 1980s as the conflict between the Sri Lankan government and Tamil militant groups escalated into a full-blown civil war. Tens of thousands crossed the narrow Palk Strait, seeking sanctuary in Tamil Nadu, a state bound to them by deep historical, linguistic, and cultural ties.

Today, over 90,000 Sri Lankan refugees live in Tamil Nadu, some in government-run camps, others integrated into local communities. Among them are more than 22,000 individuals like Ravindran—a generation born and raised entirely in India, who know no other home. They speak Tamil, celebrate Indian festivals, are educated in Indian schools, and contribute to the Indian economy. Yet, legally, they are perpetual foreigners.

This limbo is exacerbated by India’s stance on international refugee law. By not being a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, India has no formal, legal framework to handle refugees. It treats them on a ad hoc basis. While the government has generally been hospitable to Sri Lankan Tamils, providing housing and rations, the absence of a legal category for “refugee” means they are ultimately classified as “illegal migrants.” This creates a legal paradox: they are allowed to stay, but their children cannot claim belonging.

The 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which fast-tracks citizenship for persecuted non-Muslim minorities from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh, conspicuously excludes Sri Lankan Tamils. This omission, widely seen as politically motivated, has slammed shut a potential pathway to legitimacy for this community, leaving them in a permanent state of exception.

The Human Cost of Statelessness

The term “stateless” sounds abstract, but its consequences are devastatingly concrete. For Ravindran, it meant arrest on charges of cheating and forgery, 15 days in custody, and the constant fear of “coercive action.” But beyond the dramatic headlines, statelessness is a slow-burning crisis.

It means being ineligible for government jobs, scholarships, or loans. It can mean difficulties in formal employment, obtaining a driver’s license, or buying property. For young people, it can mean the shattering of dreams of higher education or a stable career. Most profoundly, it creates a pervasive sense of psychological insecurity—a feeling of not belonging, of being a guest who can be asked to leave at any moment, even when you have nowhere else to go.

Ravindran’s plea to the Madras High Court is simple: he never knowingly committed fraud. He applied for citizenship by naturalisation as soon as he was made aware of the issue. His life is in India; his wife, whom he married in Sri Lanka in a rare visit, is now part of his life in Tamil Nadu. He pledges allegiance to India, a country he has never left in spirit. His case is a test of the system’s ability to correct its own oversights with humanity.

A Glimmer of Hope and a Long Road Ahead

There are faint signs of change. In 2022, India granted citizenship to K Nalini, a Sri Lankan Tamil woman born before the 1987 cut-off. At least 13 others have followed. This sets a precedent, but it does little for the post-1987 generation. Their hope lies in either a compassionate interpretation of the law by the courts or a proactive political solution.

The Madras High Court’s interim order, restraining authorities from taking coercive action against Ravindran, is a positive step. It acknowledges the complexity of his situation. A favorable ruling could pave the way for a broader policy shift, perhaps creating a dedicated naturalisation process for those who can demonstrably prove they have lived their entire lives in India.

The plight of Bahison Ravindran and thousands like him is a challenge to India’s conscience. It forces a question: what truly defines a citizen? Is it a document, or is it a life lived? Is it the nationality of one’s parents, or is it the imprint of the soil on which one is raised? For a country that takes pride in its ancient civilization and its ethos of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (the world is one family), resolving this human-made limbo is not just a legal necessity but a moral imperative. The story of this “stateless” man is a fight for the very right to have a story, to belong to the only home he has ever known.

You must be logged in to post a comment.