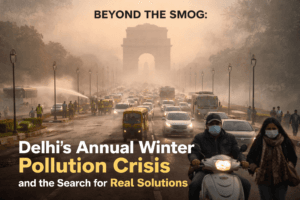

Beyond the Smog: Delhi’s Annual Winter Pollution Crisis and the Search for Real Solutions

Delhi’s air quality has deteriorated to ‘severe’ levels as of late December 2025, with its Air Quality Index (AQI) nearing 400 and many monitoring stations reporting hazardous conditions that threaten both healthy individuals and those with pre-existing health issues. This annual winter crisis is driven by a combination of meteorological factors like temperature inversion and low wind speeds, which trap pollutants from perpetual sources such as vehicle emissions and construction dust, alongside seasonal contributors including agricultural stubble burning and localized heating.

In response, the government has cited a flurry of reactive enforcement measures—including thousands of pollution challans and widespread dust suppression—while simultaneously announcing a planned collaboration with IIT Kanpur aimed at developing a more precise, granular understanding of pollution sources to enable targeted, science-driven interventions. However, the recurring nature of this severe pollution event underscores the critical need for a fundamental shift from short-term crisis management to a proactive, regional strategy that addresses the root causes through systemic changes in urban design, energy transition, and enforceable inter-state cooperation to achieve lasting improvement.

Beyond the Smog: Delhi’s Annual Winter Pollution Crisis and the Search for Real Solutions

New Delhi has once again been enveloped in a thick, toxic blanket of smog, a grimly familiar tableau for its residents each winter. As December 2025 draws to a close, the city’s air quality has plummeted to ‘severe’ levels, with an official 24-hour average Air Quality Index (AQI) hovering at a hazardous 390-397. Landmark areas like Anand Vihar, Rohini, and Punjabi Bagh have become epicentres of this public health emergency. This isn’t merely a “poor” air day; it’s a period where, as the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) warns, the air begins to affect healthy individuals and severely impacts those with pre-existing conditions. The government’s own early warning system forecasts this ‘Very Poor’ to ‘Severe’ reality will cling to the capital for days, a predictable yet unresolved annual catastrophe.

The Anatomy of a Seasonal Emergency

To understand Delhi’s winter pollution is to understand a perfect storm of human and environmental factors converging over the Indo-Gangetic Plains.

First, the meteorological trap: Winter brings lower temperatures and a phenomenon called temperature inversion, where a layer of warm air acts as a lid, trapping colder, pollutant-laden air close to the ground. Wind speeds drop to a whisper, robbing the city of its natural ventilation system. The haze isn’t just pollution; it’s this stagnant air mass, saturated with particles and gases, with nowhere to go.

Second, the contributing sources: While year-round emissions from vehicles, industries, and dust form a constant baseline, winter sees two potent additions:

- Post-Harvest Stubble Burning: Though its peak is in October-November, the particulate matter from fires in neighbouring Punjab and Haryana lingers, travelling on seasonal winds to blanket the region.

- Localised Winter Triggers: Increased use of fossil fuels for heating, rampant construction activity taking advantage of dry weather, and despite bans, sporadic but widespread firecracker usage during festivities add concentrated bursts of pollution.

The result is an AQI scale that becomes a daily health bulletin for millions. Moving from ‘Moderate’ (101-200) to ‘Poor’ (201-300) signifies discomfort for sensitive groups. ‘Very Poor’ (301-400) leads to respiratory illness on prolonged exposure. The current ‘Severe’ (401-450) and ‘Severe Plus’ (451-500) categories represent a palpable risk to all, triggering school closures and traffic restrictions, and filling hospital pulmonary wards.

Government Action: A Flurry of Activity Amidst Persistent Haze

In response to the latest spike, Delhi’s Environment Minister, Manjinder Singh Sirsa, has outlined a series of measures, presenting a picture of a government in action. The numbers are striking: over 7,000 challans for vehicular pollution, inspection of 342 construction sites, sprinkling of 1,694 km of roads, and decongestion of 41 traffic points—all reportedly in a 24-hour window.

These actions represent the standard, necessary toolkit for managing an acute crisis: enforcement, dust suppression, and traffic management. However, this reactive flurry highlights a critical, lingering question: Why does the city find itself in the same desperate situation year after year, requiring such last-minute, high-intensity interventions? The Minister’s own statement hints at the need for a paradigm shift: “Delhi will fight pollution with science, evidence and accountability… every effort must show measurable impact.”

The New Study: A Quest for Granular Clarity or Another Report to Shelve?

Perhaps the most significant, yet cautiously met, announcement is the plan for a new collaboration with IIT Kanpur. The stated goal is to move beyond broad assumptions and “identify pollution sources at a granular level, assess their impact, and enable targeted, timely interventions.”

This is both promising and fraught with déjà vu. The promise lies in the potential for hyper-local, real-time source apportionment. Imagine moving from knowing “vehicles contribute 20-30%” to knowing that at 8 AM in Connaught Place, it’s primarily diesel gensets and breakfast stall tandoors, while in Bawana at noon, it’s a mix of industrial cluster emissions and wind-blown landfill dust. Such precision could transform policy from a city-wide blunt instrument to a surgical strike on emissions.

The déjà vu stems from a history of studies and commissions. The real insight for readers lies not in the study’s announcement but in what differentiates it. Will its data be live, publicly accessible, and directly tied to mandated action? Or will it become another technical document? The emphasis on building systems to “monitor, analyse, forecast and guide action on a continuous basis” is the key phrase. The true value will be measured not in academic papers but in whether it leads to pre-emptive, data-driven alerts that prevent the AQI from touching 400 in the first place.

The Human Cost and the Path Beyond Enforcement

While governments cite AQI numbers and challan statistics, the real story is written in the lives of Delhi’s citizens. It’s in the parent’s dilemma of sending a child with asthma to school, the morning walker abandoning a lifelong healthy habit, and the street vendor enduring the haze for a full day’s livelihood. The economic cost in healthcare, lost productivity, and reduced quality of life is colossal.

Therefore, genuine insight demands we look beyond the immediate crisis management. Several pathways for lasting value and change emerge:

- Beyond the City Limits – Regional Imperative: Delhi’s air is not its own. A sustainable solution is impossible without a binding, enforceable regional cooperation framework with surrounding states on crop residue management, industrial standards, and shared green energy transitions.

- Empowering Through Transparency: The proposed IIT Kanpur system must include a public dashboard, making real-time source data available. An informed citizenry can make better daily choices and hold local authorities accountable.

- Rethinking Urban Design: The long-term game is in redesigning the city. This means accelerating the transition to 100% electric public transport, creating massive green buffers along traffic corridors, mandating green infrastructure on buildings, and prioritising compact, walkable neighbourhoods that reduce vehicular dependency.

- Shifting from Reactive to Proactive: The annual “Graded Response Action Plan” (GRAP) is a reactive protocol. The focus needs to shift massively to pre-winter action: ensuring ready availability of affordable crop residue management solutions by September, completing critical infrastructure projects before stagnation sets in, and year-round stringent enforcement on industrial and vehicular compliance.

Conclusion: A Crisis That Demands Evolution

The headline “Delhi Air Quality Hits ‘Severe’ Levels” is, tragically, not news—it’s a seasonal recurrence. The more telling headline is the government’s planning of “a new pollution study.” It signals an acknowledgment that existing knowledge and actions are insufficient.

The value for readers lies in recognising that while daily enforcement stats provide a semblance of control, the battle will only be won through systemic evolution. It requires moving from crisis management to prevention, from broad assumptions to granular intelligence, and from isolated city action to regional solidarity. The thick smog over Delhi’s winter mornings is a visible manifestation of complex policy failures. Clearing it will require more than just a strong wind; it will need an unwavering, science-driven, and collective will to redefine the very fundamentals of how the megacity and its region breathe, live, and grow. The new study will be meaningful only if it becomes the catalyst for this deeper change, ensuring that the dateline “December 2026” tells a different story.

You must be logged in to post a comment.