Beyond the Report Card: Why India’s “C Grade” from the IMF Reveals a Deeper Economic Paradox

Beyond the Report Card: Why India’s “C Grade” from the IMF Reveals a Deeper Economic Paradox

Meta Description: The IMF’s latest assessment of India praises growth while flagging data integrity and orthodox policies. This deep dive explores the gap between macroeconomic grades and the socioeconomic reality for millions.

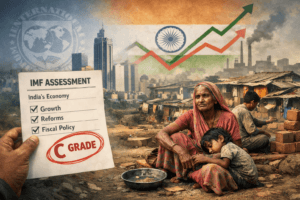

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) annual report on India, part of its Article IV consultations, presents a curious paradox. On one hand, it offers a largely laudatory view of the country’s macroeconomic management. On the other, it quietly assigns a ‘C Grade’—for the second year running—to the very foundation of that assessment: India’s national accounts and government finance data. This contradiction is more than a technical footnote; it is the key to understanding a wider chasm between the story of India’s economy as told by growth metrics and the reality experienced by its citizens.

The ‘C Grade’ is a sobering indictment from a typically diplomatic institution. It echoes long-standing concerns from independent economists about data gaps, methodological puzzles, and the invisible collapse of the unorganised sector. When monumental disruptions like demonetisation, GST implementation, and pandemic lockdowns are not adequately captured in economic models, the resulting GDP figures become a questionable portrait of prosperity. Using organised sector data as a proxy for a devastated informal economy, as critics argue happens, doesn’t just risk overestimation—it renders millions of livelihoods statistically invisible.

Yet, the 116-page report quickly moves past this foundational flaw to deliver policy prescriptions firmly within the Fund’s traditional playbook: fiscal consolidation, flexible inflation targeting, financial sector deregulation, and structural reforms aimed at boosting productivity and private investment. To a government keen on projecting ‘Vishwaguru’ status, the positive strokes are welcome. But for those analyzing India’s trajectory beyond headline growth, the report reads like a prescription from a different era, one struggling to diagnose today’s complex ailments.

The Orthodoxy and Its Blind Spots

The IMF’s four-pillar assessment—fiscal, monetary, financial, and structural—is analytically sound yet sociologically narrow.

On fiscal policy, the advice is pragmatic but constrained. The suggestion to pause deficit reduction if growth falters is sensible. However, the emphasis remains on “creating fiscal space” through improved tax administration and digital systems. Notably absent is a robust call for progressive taxation targeting the explosion of wealth at the very top. In an economy marked by stark inequality, relying on indirect taxes and improved compliance often means placing a disproportionate burden on the common citizen while the capital-rich remain relatively shielded.

On monetary policy, the recommendation for the RBI to stay “nimble” is standard. However, this framework operates on the assumption that tweaking interest rates efficiently manages demand in an economy where demand is critically weak at the bottom and concentrated at the top. Cheap credit might boost corporate investment or luxury consumption, but does little to address the acute income insecurity that stifles mass demand.

The financial sector warnings are among the report’s most pertinent, highlighting the risky rise of Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs). The concern over their exposure to sectors like power and their interconnectedness with banks is well-placed. Yet, the analysis stops at capital buffers and regulatory alignment. It misses the forest for the trees: for many low-income households, NBFCs have become the new-age sahukars (moneylenders), with lending practices that are often predatory. The systemic risk isn’t just about bad loans; it’s about a model that profits from financial distress, trapping borrowers in cycles of high-interest debt. The report’s technocratic language sanitizes this lived reality.

The Productivity Paradox and the Ghost of Manufacturing

The report correctly identifies India’s productivity puzzle. Gains are concentrated in services, while manufacturing stagnates, bogged down by a sea of micro-enterprises that cannot scale. The prescribed solution—moving labor from low-productivity agriculture to higher-productivity sectors—is a textbook mantra decades old. The question it persistently avoids is: how?

The IMF recommends easing land acquisition, modernizing records, and creating ready industrial land banks. This ignores the incendiary history of land acquisition in India, often synonymous with dispossession, eroded community rights, and environmental degradation. Pushing for “smoother” access without simultaneous, stronger safeguards for livelihoods and ecology is a recipe for social conflict, not sustainable growth.

Similarly, the advice on labor focuses on flexibility and the praised recent reforms. Framing labor purely as a “factor of production” that must be made more efficient ignores it as a community of citizens deserving dignity, security, and bargaining power. The reforms, criticized for tilting the balance overwhelmingly towards employers, may attract investment in the short term but risk cementing a low-wage, high-precarity workforce, undermining the very domestic demand needed for long-term growth.

The Glaring Omissions: Well-being Over Growth

The most significant limitation of the IMF’s framework is its philosophical core. It evaluates a “sound economy” by its ability to produce GDP growth, not by its success in ensuring socio-economic well-being. Consequently, the report has little substantial to say about:

- Universal Social Rights: There is no forceful advocacy for significantly scaled-up public investment in universal healthcare, quality education, old-age pensions, or child nutrition. Social spending is discussed as a residual “priority,” not as the engine of a healthy, productive workforce.

- The Job Crisis: The word “jobs” appears, but the profound anxiety over India’s jobless growth—despite impressive GDP numbers—is not central to the policy matrix. Creating “job-rich growth” is a stated aim, but the prescribed tools (fiscal consolidation, labor flexibility) have historically struggled to achieve it.

- Inequality as a Systemic Risk: While mentioning vulnerability, the report treats inequality as a social outcome, not a macroeconomic destabilizer. It fails to connect the dots between concentrated wealth, weak mass demand, and the resulting sluggish private investment—a core contradiction in India’s economy.

Conclusion: Grading the Grader

Ultimately, the IMF report is a mirror reflecting its own doctrinal constraints. Its ‘C Grade’ on data is an inadvertent admission that the map (the GDP figures) may not match the territory (the Indian economy). Yet, it proceeds to navigate using that very map.

The real insight for Indian policymakers and citizens lies not in the graded sections but in the gaps. It lies in asking whether the goal is to ace an international exam set to a 20th-century curriculum or to write a new syllabus focused on holistic well-being, resilience, and equitable distribution. India’s challenge is to build an economic model that respects fiscal responsibility but funds it through progressive means; that welcomes investment but not at the cost of workers’ rights and environmental justice; that prizes innovation while ensuring its fruits are widely shared.

The IMF has done its job, applying its consistent, global metric. India’s task now is to decide if that metric is enough. True economic leadership will be measured not by the praise in international reports, but by the security, dignity, and opportunity felt in the homes of its poorest citizens. On that report card, the grading has only just begun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.