Beyond the Ranking: Decoding India’s Position on the Atrocity Risk Index and the Path to Prevention

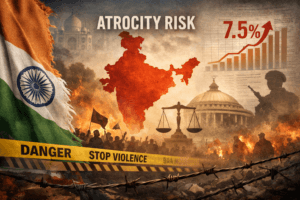

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Early Warning Project has ranked India fourth out of 168 countries—and first among nations not already in active conflict—for the risk of experiencing a new episode of mass atrocity violence by the end of 2026, with a 7.5% statistical probability. This quantitative assessment, based on historical patterns and over 30 risk factors like identity-based polarization and political instability, serves not as a prediction but as a preventive alarm bell. It highlights that India’s current societal and political climate shares characteristics with other countries before they descended into large-scale, targeted violence against civilians. The report urges Indian and international policymakers to treat this ranking as a critical starting point for proactive measures—strengthening institutions, defusing communal tensions, and preparing for potential trigger events—to steer the country away from a path where statistical risk becomes tragic reality.

Beyond the Ranking: Decoding India’s Position on the Atrocity Risk Index and the Path to Prevention

A recent study has cast a stark, analytical spotlight on India, not for its economic growth or geopolitical rise, but for a grave and unsettling potential. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Early Warning Project, in its December 2025 report, has placed India fourth globally—and first among nations not already in conflict—for the risk of experiencing a new episode of “intrastate mass killing” before the end of 2026. With a calculated 7.5% probability, this assessment is not a prophecy of doom but a statistically-driven alarm bell. Understanding what this means, why it matters, and, crucially, what can be done about it requires moving beyond the headline and into a nuanced examination of risk, resilience, and responsibility.

Deconstructing the Diagnosis: What the Report Actually Measures

First, it is imperative to grasp what the Early Warning Project does—and does not—say. This is not a qualitative political critique but a quantitative risk model. Researchers from the Museum and Dartmouth College feed over three decades of historical data into an algorithm, identifying patterns and variables that were present in countries in the one to two years preceding outbreaks of mass atrocities. They then scan the world for nations that currently exhibit similar patterns.

The specific crime they monitor is precise: the deliberate killing of at least 1,000 non-combatant civilians within a year, targeted based on their group identity (ethnicity, religion, political affiliation, or region). The model analyzes over 30 factors, including demographic pressures, economic indicators, levels of political freedom, and histories of armed conflict.

Lawrence Woocher of the Museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide emphasizes the core philosophy: the Holocaust was preventable. The project’s goal is to shift the international community from reaction to prevention by highlighting where warning signs are flashing. India’s position is particularly notable because it tops the list of “at-risk” countries that are not currently engulfed in such large-scale violence, unlike Myanmar, Sudan, or Chad ranked above it. This marks it not as a crisis zone, but as a potential prevention priority.

The Indian Context: Where Statistical Risk Meets Societal Reality

A 7.5% risk is, statistically, not a certainty. But in the realm of mass atrocities, where the human cost is catastrophic, it is a percentage that demands sober reflection. The model does not pinpoint causes, but it identifies correlated conditions. When these conditions are overlaid onto India’s contemporary landscape, several areas of concern emerge, forming a complex risk ecosystem.

- Identity-Based Polarization:The very definition of the monitored violence hinges on group identity. India has witnessed a deepening of societal fractures along religious and ethnic lines. Narratives of majoritarianism versus minority persecution, while fiercely contested in the political arena, contribute to an “us vs. them” discourse. This social polarization is a classic precursor identified in atrocity risk models, as it dehumanizes the “other” and creates a permission structure for violence.

- Trigger Events in a Volatile Climate:The report explicitly asks what specific triggers—elections, political upheaval, protests—could spark violence. India’s political cycle is inherently high-stakes. Closely fought elections, contentious legislation (perceived to favor or disfavor specific communities), and major judicial rulings act as potential flashpoints. In an environment of heightened communal rhetoric and pervasive social media misinformation, localized incidents can escalate with terrifying speed into wider conflagrations, as history has tragically shown.

- The Erosion of Institutional Buffers:Strong, independent institutions—the judiciary, a non-partisan police force, a free press, a robust civil society—act as critical buffers against mass violence. They mediate conflict, hold perpetrators accountable, and provide checks on power. Persistent concerns regarding the weakening of these institutional safeguards, whether perceived or real, feature in risk assessments. When public trust in these arbiters declines, communities may feel unprotected or justified in taking matters into their own hands.

- Historical Precedents and Unhealed Wounds:The model weighs historical factors. India’s history, while largely peaceful at a national scale, is punctuated by severe episodes of communal and caste-based violence. These historical memories are not inert; they inform present-day fears and grievances. In regions with a history of insurgency or ethnic strife, such as parts of the Northeast or Kashmir, underlying tensions remain palpable and can be reignited.

Prevention, Not Prediction: From Fatalism to Action

The most critical part of the report is its insistence that this is a tool for prevention, not a fatalistic prediction. It explicitly states that the variables are correlative, not causal. A large population doesn’t cause violence, but it is a factor in the statistical model. This distinction is empowering: it means risk is not destiny.

The report’s recommendations provide a blueprint for a proactive response:

For Indian Civil Society and Media: This is a call for vigilant, responsible, and courageous journalism and activism. It underscores the need to document hate speech, monitor vulnerable communities, build inter-faith and inter-community bridges, and demand accountability for violence. The focus must be on reinforcing the societal immune system.

For the Indian Government: The dignified response is not to dismiss the report but to engage with its framework. It should prompt confidential, high-level audits within security and policy circles. Are early-warning systems within the police and intelligence apparatus sensitive to identity-based violence? Are disaster management protocols adaptable for human-made catastrophes of this nature? Investing in community policing, swift and impartial justice for riot victims, and demonstrably protecting minority rights are not concessions but essential investments in national stability.

For the International Community: As the report advises, the global policy community must move beyond simplistic engagement. This is not about imposing solutions but about smart, context-sensitive support. This could mean funding local peacebuilding initiatives, facilitating track-II dialogues on communal harmony, sharing best practices on atrocity prevention from other diverse democracies, and using diplomatic channels to consistently emphasize the importance of inclusive governance and human rights.

Conclusion: The Choice in the Data

The Holocaust Museum’s ranking is an uncomfortable mirror. It reflects back a set of conditions that, when left unaddressed, have historically paved the way for unthinkable violence. India’s position is less an indictment of its present than a caution about a possible future.

The nation stands at a crossroads familiar to many large, diverse societies. One path, paved with apathy, denial, and escalating division, leads toward the statistical risk becoming a tragic reality. The other, built on conscious, collective effort, leads toward resilience. It involves strengthening democratic institutions, healing communal fractures, empowering local peacemakers, and remembering that the strongest nations are not those without tensions, but those that resolve them justly and peacefully.

The 7.5% figure is not a verdict. It is a warning siren. The power to silence that siren lies not in disputing the algorithm, but in the collective will to change the data points it feeds on—to replace polarization with pluralism, suspicion with solidarity, and risk with resilience. The future, as always, remains to be written.

You must be logged in to post a comment.