Beyond the Queue: William Dalrymple, the Jaipur Lit Fest, and the Myth of the Non-Reading Indian

Beyond the Queue: William Dalrymple, the Jaipur Lit Fest, and the Myth of the Non-Reading Indian

There is a specific, almost sacred quiet that descends upon the Diggi Palace Hotel in Jaipur every January. It is a quiet born of thousands of people holding their breath simultaneously, heads tilted, listening to poets, historians, and novelists spin language into gold. Then, the session ends. The quiet shatters, replaced by the shuffle of feet and the crisp rustle of paperbacks being pulled from bags.

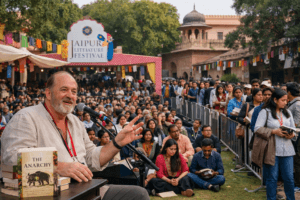

This is the scene that greeted Nobel Laureates and Booker Prize winners at the 19th edition of the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) last month. It is also the scene that historian William Dalrymple evoked this week in a blistering social media takedown of The Guardian, a publication that recently questioned why a country with allegedly low rates of “reading for pleasure” hosts over 100 literary festivals.

“Irritating & ignorant,” Dalrymple wrote. He wasn’t just defending a festival he co-founded; he was defending the dignity of millions of Indian readers who remain invisible to foreign observers unless they are being quantified in spreadsheets.

The brief war of words between a British historian and a British newspaper, playing out on a global platform, has inadvertently illuminated a much larger truth: The West is very bad at measuring how India reads.

The Spectacle vs. The Substance

The offending article posited a paradox that exists only in the mind of the beholder. To the writer, the glittering tents of Jaipur—filled with celebrities, politicians, and branded coffee kiosks—seemed at odds with a nation where literacy surveys suggest deep reading is in decline.

It is a familiar colonial hangover: the assumption that if something isn’t done in English, in a library, silently, and with a frown of concentration, it isn’t “serious” reading.

Dalrymple’s rebuttal was simple, data-driven, and devastating. He noted that JLF 2026 sold over 44,000 books in just five days. Not book signings given away for free, but books purchased by attendees who carried them home to shelves already buckling under the weight of previous hauls.

But the statistic that stung harder was the one about queues. Dalrymple noted that authors at JLF “regularly report the longest signing queues of their careers.” This is not a trivial metric. When an international author travels from London or New York to Jaipur and spends two hours writing their name in dog-eared copies of their work, they are experiencing a reality that cannot be captured by a Nielsen BookScan report.

The Queue as Cultural Evidence

To understand why the queue is such a powerful rebuttal, one must understand the logistics of the Jaipur Literature Festival. The venue is not a cavernous convention center with air-conditioned corridors. It is a walled garden in the heart of the Pink City. Attendees stand for hours in the Rajasthani sun, temperatures hovering in the low 20s Celsius (70s Fahrenheit), often packed so tightly that moving one’s elbows is a challenge.

These are not corporate delegates looking for networking opportunities. As Dalrymple described them, they are “passionate, nerdy young readers.”

I met one such reader last month. His name is Akash, a 22-year-old engineering student from Kota. He had traveled six hours by bus, clutching a heavily annotated copy of a translated Bengali novel. He couldn’t afford the hotel rates in Jaipur, so he planned to stay awake all night at the railway station waiting room before catching his return train.

“In my college, if you read Hindi literature, your friends call you ‘old school,’” he told me. “But here, everyone is reading. The person next to you is reading something you’ve never heard of. That is the addiction.”

This is the ecosystem the Western media often misses. It is not a library culture; it is a bazaar culture. It is loud, messy, and deeply social.

The Flawed Metrics of a Literary Deficit

The argument that “Indians don’t read” usually hinges on surveys measuring leisure reading in English. This is like measuring the health of Italian cuisine by only reviewing restaurants in Iceland.

India has 22 official languages and hundreds of dialects. The publishing industry in Hindi, Bengali, Marathi, Tamil, and Urdu is not merely surviving; in many segments, it is thriving. The Jaipur Literature Festival has made concerted efforts in recent years to amplify Bhasha (vernacular) writers. Banu Mushtaq, the International Booker Prize winner who spoke at the 2026 edition, represents a literary tradition that predates the English novel by centuries.

Furthermore, the definition of “reading” in India is historically expansive. The oral traditions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata were preserved through recitation and listening. Even today, a slum in Mumbai might not have a public library, but it will have a paan shop where dog-eared thrillers and pulp fiction are rented for five rupees a day.

One user responding to the controversy noted the cognitive dissonance perfectly: “There is a lot of fanfare and glamour even at the Frankfurt Book Fair—does that mean Germans don’t read?”

The question is rhetorical, yet cutting. We accept that Germans can host a massive, commercially successful book fair while maintaining a sophisticated reading culture. When India does the same, it is pathologized as superficial.

The Kolkata Benchmark

While the Jaipur Literature Festival captures the global headlines, veteran readers point to an older, perhaps more authentic testament to India’s bibliophilia: the Kolkata Book Fair.

Unlike JLF, which is a ticketed, curated, speaker-heavy event, the Kolkata Book Fair is a boisterous trade show. It is muddy during rain, chaotic during rush hour, and absolutely teeming with life. Families attend not as a status symbol, but as an annual pilgrimage.

As one observer commented in the wake of the Guardian controversy, “People patiently standing for hours in queues without any pushing or shoving to buy a book.”

That phrase—“without any pushing or shoving”—is striking. In a country often stereotyped for its chaotic crowds, the book fair queue remains a peculiar oasis of civility. It suggests a shared respect for the object being acquired.

Why the ‘Ignorance’ Stings

Dalrymple’s use of the word “ignorant” is precise. It is not just that The Guardian got the facts wrong; it is that they failed to look for the facts in the right places.

India suffers from a specific kind of stereotyping in global literary discourse. It is simultaneously accused of not reading enough and of producing derivative, post-colonial literature when it does. The success of the Jaipur Literature Festival—now the largest free literary festival in the world—disrupts that narrative.

If Indians didn’t read, the festival would have died in its infancy. Instead, it has birthed imitators. There is now a proliferation of literary festivals in places like Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kerala, and even the Himalayan foothills. The market, in this case, is not lying. Sponsors do not throw money at events that attract empty chairs.

The ‘Nerd’ Vindication

Perhaps the most heartening response to Dalrymple’s tweet came from the readers themselves.

“As an Indian nerd that grew up surrounded by nerds who read only for pleasure—Thank you,” one user wrote.

There is a loneliness that comes with being a heavy reader in a country where infrastructure—libraries, bookstores, literary cafes—is often lacking outside of major metros. For years, these readers existed in silos, communicating via decrepit forums or waiting months for a specific import to arrive at a local shop.

The literature festival movement changed that. It validated the “nerd.” It turned a solitary act into a communal celebration. For a teenager in a small town, seeing a Pulitzer Prize winner speak in person is not just entertainment; it is proof that the world they inhabit in their imagination is real.

The Uncomfortable Truth for Foreign Media

The Guardian’s framing suggests that India’s literary festivals are a symptom of aspirational consumerism rather than intellectual hunger. There is no doubt that some attendees go to JLF to see celebrities or to be seen. That is true of the Hay Festival, true of Frankfurt, and true of the Brooklyn Book Festival.

But to suggest that the spectacle negates the reading is a logical fallacy. The 44,000 books sold at JLF were not bought as props. They were carried home, read, debated, and likely lent to friends.

Dalrymple did not need to defend India. India’s readers defended themselves, one queue, one book purchase, one overnight train journey at a time. But his intervention was necessary because it came from an outsider—a Scottish-born historian who has made India his home and his life’s work.

When he calls an article “irritating and ignorant,” it carries the weight of someone who has spent decades standing in those signing queues, watching the young “nerds” file past with trembling hands and overflowing totes.

Conclusion: Reading as Resistance

In an era of shrinking attention spans and algorithmic content feeds, the decision to buy a physical book, travel with it, and wait in line to meet its creator is an act of quiet resistance.

India, with its 100+ literature festivals and its 44,000-book weekends, is not suffering from a deficit of reading. It is suffering from a deficit of accurate reporting.

The next time a foreign publication questions the literary appetite of 1.4 billion people, they would do well to skip the census data and the think tank reports. Instead, they should book a ticket to Jaipur in January. They should arrive early, before the sun gets high, and stand at the back of the Durbar Hall.

You must be logged in to post a comment.