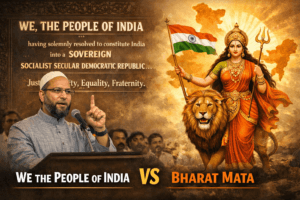

Beyond the Preamble: Why Owaisi’s “We the People” vs. “Bharat Mata” Debate Cuts to India’s Constitutional Core

AIMIM chief Asaduddin Owaisi’s emphasis that the Indian Constitution begins with “We the People” and not “Bharat Mata” underscores a fundamental debate about the nation’s identity, contrasting the document’s secular, inclusive framework of popular sovereignty with a majoritarian cultural nationalism. By anchoring his argument in the Preamble’s values and Article 25’s guarantee of religious freedom, Owaisi defends a civic conception of India where belonging and patriotism are derived from constitutional commitment and the shared sacrifices of a diverse freedom struggle, rather than through devotion to a singular religious-cultural symbol, thereby challenging narratives that risk making equal citizenship conditional on adherence to a particular cultural expression.

Beyond the Preamble: Why Owaisi’s “We the People” vs. “Bharat Mata” Debate Cuts to India’s Constitutional Core

The political discourse in India often revolves around potent symbols—words, icons, and slogans that carry the weight of history and ideology. In one such moment, Asaduddin Owaisi, the president of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), recently underscored a fundamental, yet frequently contested, detail: the Indian Constitution begins with the English words “We the People of India,” not with an invocation to “Bharat Mata.” This statement, made during a public rally in Sadasivpet, is far more than a semantic correction. It is a deliberate spotlight on the philosophical bedrock of the republic—a defense of its secular, inclusive character against a rising tide of majoritarian cultural nationalism.

Owaisi’s remarks, situated within the parliamentary debate on the 150th anniversary of Vande Mataram, were not an attempt to diminish patriotic sentiment. Instead, they were a pointed reminder of the document’s architecture. By highlighting the Preamble’s chosen words, he invoked the very source of the Constitution’s authority: the collective will of India’s diverse populace. This stands in deliberate contrast to a conception of the nation as a divine, singular, and often implicitly Hindu mother goddess. The distinction is not academic; it is the line that separates a civic nation from an ethno-religious one.

The Preamble as a Philosophical Anchor

To understand the gravity of this distinction, one must revisit the Constituent Assembly debates. The framing of the Preamble was a subject of intense deliberation. Proposals to invoke “God” or “Gandhian principles” were considered and ultimately rejected in favor of a stark, powerful statement of popular sovereignty and shared goals. The final draft, inspired in part by the American model, was a conscious choice to ground the nation’s highest law in the authority of its people—all its people, irrespective of faith, caste, or ethnicity.

The values that follow—“Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity”—are the secular gospel of the Indian republic. They are guarantees meant to be enjoyed by every citizen. Owaisi’s linkage of this to Article 25, which guarantees freedom of conscience and free profession, practice, and propagation of religion, is crucial. It underscores that the Constitution explicitly protects the right to worship (or not worship) according to one’s own beliefs. Tying patriotism to the veneration of a specific religious symbol, therefore, creates a direct tension with this constitutional guarantee. It risks creating a hierarchy of patriotism, where those whose cultural expression aligns with the majority are deemed “more Indian.”

Historical Sacrifices and Inclusive Nationalism

Owaisi’s rhetorical questions—“What answer will you give to Bahadur Shah Zafar?… What answer will you give to Yusuf Meherally?”—are a powerful counter-narrative. By citing the last Mughal emperor, who died in exile after the 1857 rebellion, and the socialist freedom fighter who coined the slogans “Quit India” and “Simon Go Back,” he reclaims a pluralistic history of the freedom struggle. This history is populated by individuals whose contributions were monumental but whose personal faith or cultural expression might not fit a monolithic “Bharat Mata” paradigm.

This argument challenges the notion that national love must flow through a single religious or cultural channel. It asserts that the sacrifice of a Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, or atheist freedom fighter holds equal value in the making of modern India. To reduce patriotism to a religious test is, as Owaisi stated, to dishonor this composite legacy. It intellectually disenfranchises communities from the national narrative, making their belonging conditional.

The Symbolic Battle: “Bharat Mata” in the Public Sphere

The figure of Bharat Mata (Mother India) has a complex history. Emerging as a powerful artistic and poetic symbol in the late-19th and early-20th century nationalist movement, she was a unifying emblem against colonial rule. However, in contemporary politics, her imagery has been increasingly co-opted and homogenized, often depicted in a specifically Hindu-iconographic style, akin to the goddess Durga. The mapping of the nation’s geographical boundaries onto this religious imagery creates a potent, but exclusionary, fusion of faith and geography.

The debate, therefore, is about the state’s relationship with this symbol. Should the state, bound by a secular constitution, officially endorse or propagate a symbol so deeply entwined with one religion’s iconography? Owaisi’s emphasis on the Preamble is a plea for the state to remain neutral—to be the guardian of all faiths and the property of none. It is an argument for the public square to be shaped by the constitutional values of liberty and equality, rather than any particular religious sentiment, however popular.

The Enduring Relevance of the Argument

This is not a new debate, but its urgency is renewed in today’s socio-political climate. When questions of “anti-national” activity are often conflated with dissent or minority identity, reaffirming the original, constitutional basis of citizenship becomes an act of preservation. The “We the People” formulation is inherently democratic and participatory. It invites every citizen to see themselves as the author and the subject of the Constitution. “Bharat Mata,” in its politicized form, can become a passive object of devotion, with gatekeepers defining the terms of that devotion.

The genius of the Indian Constitution lies in its ability to hold together a staggering diversity within a single political framework. Its Preamble is the glue. To replace its foundational, inclusive language with any other symbol or phrase—however emotionally resonant for many—is to alter the fundamental self-definition of the state. It shifts the basis of the nation from a social contract among people to a cultural or religious abstraction.

Conclusion: The Preamble as a Living Promise

Asaduddin Owaisi’s statement is ultimately a conservative one in the truest sense—it seeks to conserve the original intent and framework of the Indian Republic. It is a call to return to the document that was solemnly adopted on January 26, 1950, as the ultimate guide for the nation’s journey. In a noisy political landscape filled with competing symbols and slogans, he points back to the quiet, profound words at the beginning of the book of law.

The “We the People” vs. “Bharat Mata” debate is, at its heart, a struggle over India’s soul. Will it be a nation where belonging is derived from a shared commitment to constitutional values and collective building of the future? Or will it be a nation where belonging is increasingly mediated through a specific cultural and religious lens? The Constitution’s Preamble has already given its answer. The ongoing political challenge is whether a diverse and argumentative democracy can continue to live up to that founding, secular promise. The choice between those opening words is, therefore, a choice about the very character of the Indian experiment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.