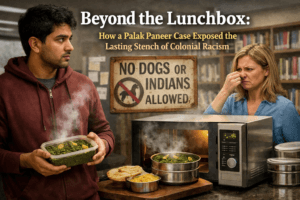

Beyond the Lunchbox: How a Palak Paneer Case Exposed the Lasting Stench of Colonial Racism

The $200,000 settlement secured by two Indian scholars in a U.S. racial discrimination case, sparked by a complaint over reheating palak paneer, represents far more than a dispute about food smells; it is a potent symbol of the enduring “Dogs and Indians” colonial mindset, where critiques of South Asian cuisine serve as a socially acceptable proxy for deeper racism. The incident, involving a British staff member’s “pungent” remark and the university’s subsequent institutional retaliation—which derailed the scholars’ academic careers—highlights how “olfactory discrimination” polices cultural belonging and reinforces power hierarchies. Ultimately, the case is a moral victory that exposes the subtle, systemic biases within Western institutions, challenging the normalization of humiliating cultural expressions and asserting that such discrimination carries significant social and economic consequences.

Beyond the Lunchbox: How a Palak Paneer Case Exposed the Lasting Stench of Colonial Racism

For Aditya Prakash, reheating his palak paneer in a university microwave was a simple act of sustenance. For a staff member in the department, it was an olfactory offense. What unfolded from that 2023 encounter—a $200,000 legal settlement, derailed academic careers, and a fierce public debate—transcended a mere disagreement over smells. It became a stark, modern parable about how colonial-era hierarchies continue to police cultural belonging in the West, using the familiar, intimate medium of food as their weapon.

The common dismissal of such incidents as hypersensitivity misses the profound historical weight they carry. As Prakash and his fiancée, Urmi Bhattacheryya, articulate, this was never about a dish of spinach and cottage cheese. It was about the reactivation of a centuries-old code: the unwritten rule that certain cultures, and their most visceral expressions, are inherently “pungent,” “other,” and unwelcome in shared civilized spaces.

The Colonial Nose: From “Dogs and Indians” to “Pungent” Food

The most potent symbol invoked by the scholars is the infamous “Dogs and Indians Not Allowed” signs from British-ruled India. This was not merely segregation; it was a deliberate symbolic coupling designed to dehumanize, to place a people on the periphery of the moral and social universe. The accusation that Indian food is “smelly” or “pungent” operates on the same continuum. It doesn’t describe a neutral sensory fact but makes a cultural judgment. It labels the cuisine, and by extension the people who cherish it, as intrusive, unclean, and disruptive to the normative (read: Western) environment.

This “olfactory discrimination” is a well-documented tool of racism. It provides a socially plausible cover for prejudice—“It’s not you, it’s the smell”—while drawing a direct line to colonial anthropology, which often described colonized lands and peoples in terms of overwhelming, strange, and unpleasant odors. The staff member’s subsequent escalation—claiming the microwave was too close to her space—laid bare the power dynamic. It wasn’t about ventilation; it was about who holds the authority to define what is acceptable in a shared space.

The Bitter Irony of Academia’s Complicity

The setting of this incident adds a layer of profound irony: a university anthropology department. This is a discipline built on studying, documenting, and theorizing human culture. Yet, when living, breathing culture entered its own breakroom, it was pathologized. As the scholars noted, Western academia often builds careers on researching marginalized communities in India, yet fails to extend basic respect to the cultural practices of Indians in its midst. The department’s ultimate solution—banning all microwave use—was a classic act of institutional neutrality that only entrenched the discrimination. By refusing to address the specific prejudice and instead punishing everyone, they validated the initial complaint, permanently stigmatizing the act of heating Indian food.

The Real Cost: Silenced Voices and Shattered Careers

The $200,000 settlement, while significant, is only the monetary footnote to a story of profound academic and personal cost. The true injury was the institutional retaliation that followed their complaint. The resignations of advisory committees, the loss of research funding and teaching roles, and the imposed isolation reveal a brutal truth: challenging microaggressions can trigger macro-punishments. Their perfect GPAs and secured grants became irrelevant in the face of an institution closing ranks. Their experience echoes a silent epidemic among international students and scholars—the fear of speaking up against casual racism because the price is often one’s career trajectory.

Food as Identity, Resistance, and the Path Forward

For immigrants and diasporic communities, food is never just fuel. It is a repository of memory, a language of love, and a tangible connection to a homeland. Prakash’s memory of being shunned for his paratha-sabzi in Italy at age 14 highlights how early these lessons in othering are learned. The “lunchbox moment” is a universal rite of passage for many non-white children in the West, often shaping their sense of shame or pride.

The solidarity response from other students—bringing Indian food to campus—was a powerful, culturally-rooted act of civil disobedience. It reframed the issue from one individual’s complaint to a collective claim for space and belonging. It said, Our culture is not an apology.

The moral victory Prakash and Bhattacheryya claim is crucial. It demonstrates that “olfactory racism” is legally actionable and socially costly for institutions. It sends a message that the casual humiliation of one’s culture can have serious consequences. However, the settlement’s condition—that they can never study or work at the institution again—also underscores the lingering punitive attitude.

Ultimately, the palak paneer case is a mirror held up to Western institutions, particularly those that pride themselves on liberalism and diversity. True inclusivity isn’t just about recruitment brochures featuring diverse faces; it’s about whether the smell of cumin, turmeric, and fenugreek is tolerated in the staff kitchen. It’s about recognizing that the right to one’s culture includes the right to its aromas, without being subjected to a colonial-era hierarchy of senses.

The journey from “Dogs and Indians Not Allowed” to “Your Food is Pungent” is shorter than we’d like to believe. Bridging that gap requires more than diversity training; it requires a fundamental rethinking of whose comfort is prioritized, whose culture is deemed neutral, and who truly belongs in spaces we call shared. As this case proves, sometimes that fight for dignity begins with something as simple, and as profound, as a heated lunch.

You must be logged in to post a comment.