Beyond the Law: Inside Afghanistan’s New Criminal Code That Divides Citizens by Class and Gender

The Taliban’s newly implemented Criminal Procedure Code in Afghanistan formalizes a class-based justice system that explicitly treats citizens differently based on their social standing, with religious authorities and elites receiving lighter sanctions while lower classes face harsher punishments including public flogging and imprisonment for the same offenses. The 100+ article code deepens restrictions on women by narrowing domestic violence prosecution pathways—requiring severe visible injury for cases to proceed and capping sentences at as little as 15 days—while using terminology like “slave” and “master” in legal classifications, prompting widespread condemnation from human rights organizations who argue it transforms arbitrary repression into legally sanctioned inequality and institutionalizes violence against women, children and marginalized groups under the guise of Islamic jurisprudence.

Beyond the Law: Inside Afghanistan’s New Criminal Code That Divides Citizens by Class and Gender

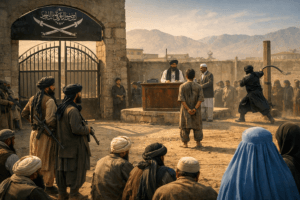

The gates of the appeals court in Kabul cast long shadows across the dusty courtyard where a small crowd has gathered. Inside, a man awaits judgment for a crime that, depending entirely on who he is—his tribal affiliation, his economic standing, his connections to religious authority—could result in anything from a quiet warning to a public flogging that leaves scars for life.

This is justice in the new Afghanistan, where the Taliban’s recently unveiled Criminal Procedure Code has transformed what was once ad-hoc enforcement into a formalized system of hierarchy. The 100+ article document, signed by Supreme Leader Hibatullah Akhundzada and implemented in early 2026, does more than establish rules—it inscribes inequality into the very fabric of Afghan law.

The Architecture of Unequal Justice

When human rights lawyer Mariam Safi first obtained a copy of the new code, she spent three days cross-referencing its provisions with her dog-eared copies of international human rights conventions and Afghanistan’s now-defunct 2004 constitution. What emerged was a portrait of a legal system that explicitly treats citizens differently based on their social standing.

“The code doesn’t hide what it does,” Safi explains via a crackling phone connection from an undisclosed location. “It creates categories of people. Religious scholars and community elders—what they call ‘the worthy classes’—face different consequences for identical actions than ordinary citizens. And beneath them all are the marginalized, the poor, the internally displaced, who now understand that the law exists primarily as an instrument against them.”

The mechanism is subtle on paper but brutal in practice. Under the code’s discretionary ta’zir provisions—punishments not fixed by Islamic law but left to judicial discretion—judges receive explicit guidance to consider the defendant’s “social position, religious standing, and community value” when determining sentences. For those at the top of the hierarchy, this might mean a quiet conversation with local clerics. For those at the bottom, it means lashes, imprisonment, or worse.

A Morning in Mazar-i-Sharif

In Mazar-i-Sharif, a 34-year-old fruit seller who asked to be identified only as Hamid describes what happened when his neighbor accused him of a land dispute that escalated to blows. Under any rational legal system, the case might have been simple assault. But Hamid’s family has no tribal connections in the province, having fled Kunduz two years ago during the final battles before the Taliban consolidation.

“They asked me first about my father, my grandfather, where our family originated, who could speak for us,” Hamid recounts, sitting in a tea house where he now earns a fraction of what he once did. “When I explained we were alone here, the judge’s demeanor changed. He spoke to the other man differently—he was from a local family, known to the mullahs.”

Hamid received thirty lashes and a fine he cannot afford. His neighbor received a warning and was told to “seek reconciliation.” This is the code in practice: a system that reads your worth from your origins.

The Gender Provisions: When Law Becomes Weapon

Perhaps nowhere is the code’s impact more devastating than in its treatment of women. The provisions dealing with domestic violence have drawn particular outrage from human rights monitors—and for good reason.

Under the new framework, a husband’s violence against his wife only becomes a criminal matter if the victim can demonstrate “severe visible injury.” The code does not define what constitutes “severe,” leaving that determination to the same judges who already operate within a framework that views women as inherently lesser legal subjects. Even when such injury can be proven, the maximum penalty in many documented cases has been fifteen days imprisonment—a sentence that some Afghan women’s rights activists note is shorter than the recovery time for the injuries themselves.

“We have documented cases where women who sought protection were sent back to their husbands after being told to be better wives,” says Fatima Haidari, who coordinates a underground network of women documenting human rights abuses. “The message is clear: the law does not see you as an individual with rights. It sees you as part of a man’s household, and it will not intervene in how he manages his property.”

The contrast with provisions protecting property or addressing animal cruelty has become a rallying point for critics. International observers have noted that the penalties for harming a neighbor’s livestock can, in some interpretations of the code, exceed those for harming a wife. Whether this reflects actual judicial practice varies by region, but the symbolic weight is unmistakable: in the hierarchy of protection, women have been placed below valuable animals.

The Return of Public Punishment

On a Friday afternoon in Logar province, residents of a small village were summoned to the local sports field. The occasion was a public punishment session—four individuals convicted of various offenses under the new code would receive their sentences before the community.

Among them was a young woman accused of “illicit relations,” a charge that under the code requires minimal evidence and offers maximum discretion. She received fifty lashes, administered by a man who had been her cousin’s neighbor. The crowd, according to witnesses who spoke to researchers on condition of anonymity, was predominantly male. The women who might have known her, who might have understood the circumstances of her case, were not present—their attendance at such events is discouraged under separate Taliban edicts restricting women’s public participation.

These scenes are becoming routine across Afghanistan. Data compiled from Taliban court announcements shows dozens of floggings monthly, with sentences ranging from twenty to one hundred lashes. The offenses vary—theft, alcohol, “moral crimes”—but the message is consistent: punishment is public, justice is visible, and the state’s power over bodies is absolute.

The Ghosts of Legal Language

Legal scholars have noted something else troubling in the code: terminology that suggests a troubling regression in basic human rights concepts. The document uses terms like “slave” and “master” in its classifications—language that international human rights law had hoped was consigned to history. While Taliban officials insist these are translations of traditional Islamic legal categories rather than an endorsement of actual slavery, human rights monitors point out that language shapes reality.

“When a legal code uses the vocabulary of ownership and bondage, it creates conceptual space for those relationships to exist,” explains Dr. Abbas Mohammadi, who taught comparative law at Kabul University before the Taliban takeover. “Even if the drafters didn’t intend to legalize slavery—and I’m not sure they didn’t—they’ve created a framework where treating certain humans as property becomes thinkable within the law’s logic.”

This linguistic regression mirrors broader patterns in the code’s approach to human dignity. The concept of universal human rights, of protections that apply regardless of status or identity, finds no home here. Instead, the code constructs a world where your rights are precisely calibrated to your position in a hierarchy that predates modernity and rejects its core premises.

Children in the Crosshairs

The code’s provisions regarding children have received less international attention than those affecting women, but activists on the ground describe them as equally devastating. Juvenile offenders face a system that makes few distinctions between minors and adults in practice, despite nominal protections on paper.

“Children as young as twelve have been detained alongside adults, subjected to the same interrogation methods, facing the same discretionary punishments,” says a researcher with a international children’s rights organization who requested anonymity to protect their safety. “The concept of juvenile justice, of rehabilitation rather than punishment, of special protections for minors—none of this exists in the operational reality of the new courts.”

For girls, the situation is compounded. A female child accused of any offense faces not only the legal system but also the social destruction that follows. Families may disown daughters who bring shame through legal entanglement, leaving them with nowhere to go and no protection. The code provides no special provisions for these circumstances, no recognition that children might need different treatment than adults.

The International Response: Condemnation Without Consequence

In Canberra, London, Brussels, and Washington, officials have issued statements condemning the new code. Sanctions have been imposed on specific Taliban officials. Travel bans target those deemed most responsible for human rights deterioration. The United Nations has added Afghanistan to its list of grave concerns regarding women’s rights.

Yet inside Afghanistan, the floggings continue. The courts keep issuing their stratified judgments. Women keep being told that their injuries don’t meet the threshold for legal intervention.

“The international community has run out of ideas,” admits a European diplomat who follows Afghanistan closely but cannot speak publicly about policy. “We’ve tried sanctions, we’ve tried engagement, we’ve tried isolation. Nothing has changed the fundamental calculus of a movement that believes it has won, that believes history is on its side, and that believes human rights as the West defines them are a form of cultural imperialism to be resisted.”

This analysis may be too kind to international actors. Critics point out that meaningful leverage—recognition of the Taliban government, access to international financial institutions, release of frozen assets—remains largely unused as a bargaining chip. The international community condemns but continues to engage, criticizes but continues to negotiate, creating a dynamic where the Taliban can absorb rhetorical blows while maintaining their domestic agenda unchanged.

Life Under the Code: Voices from the Ground

In a cramped apartment in Kabul’s outskirts, three generations of women gather weekly to share news, support each other, and maintain a fragile sense of normalcy. The oldest, a grandmother in her sixties who remembers life before the first Taliban regime, before the American invasion, before everything, speaks of the new code with weary resignation.

“We have seen laws come and go. We have seen constitutions promise everything and deliver nothing. This is just another name for what has always been true here: if you are a woman, if you are poor, if you have no one to speak for you, the law is what happens to you, not what protects you.”

Her daughter-in-law, a former teacher now confined to the home under Taliban edicts banning women from most employment, is less philosophical. “They have written down what they always believed. The paper doesn’t change anything—it just makes it official. Now when they beat us, when they take our children, when they deny us everything, they can point to a document and say ‘this is law.’ Before, at least they had to pretend shame.”

The youngest, a seventeen-year-old who has never known an Afghanistan where girls could attend secondary school, listens silently. When asked about her future, she shrugs. “What future? They have written it for me. I will marry someone they choose, I will bear children they count, and if I survive, I will become my grandmother, telling stories to girls who will also have no choices.”

The Theological Framework

Taliban officials defend the code as authentically Islamic, rooted in centuries of jurisprudence rather than Western imports. In interviews with sympathetic media, they argue that universal human rights are a cultural construct, that Islamic societies have their own traditions of justice, and that the international community has no standing to judge.

This argument finds some resonance among Muslims worldwide who chafe at Western moral hegemony. But Islamic scholars critical of the Taliban point out that Islamic jurisprudence contains robust traditions of justice, protections for the vulnerable, and limitations on state power that the code ignores.

“Islam did not invent class-based justice—it emerged in a society that practiced it, and the revelation consistently pushed against it,” argues Sheikh Ahmed Rashidi, a London-based Islamic scholar who has studied the code. “The idea that a rich man and a poor man should receive different punishments for the same crime contradicts the Quranic emphasis on justice as blind to worldly status. The Taliban are not reviving Islamic law—they are inventing a version of it that serves their political and social agenda.”

This theological debate, however, occurs largely outside Afghanistan. Inside the country, dissent is dangerous, and few religious voices risk challenging an interpretation backed by armed power.

Economic Dimensions of Legal Stratification

The code’s class dimensions extend beyond punishment to the entire legal process. Access to justice under the new system requires resources that poor Afghans simply don’t have. While the Taliban have nominally simplified procedures, the reality is that navigating the system requires bribes, connections, and the ability to wait—often for weeks—while cases proceed.

“The poor don’t go to court unless they’re dragged there,” says a Kabul-based fixer who helps international journalists navigate the city. “If you have a dispute, you try to solve it yourself, because once the system touches you, it never lets go without taking something. The rich—they have people, they have money, they have the names of mullahs to drop. The system works differently for them.”

This economic reality reinforces the code’s explicit hierarchy. Those with resources can access whatever protections the system offers. Those without become its raw material—the bodies on which the state demonstrates its power through public punishment, the examples held up to deter others.

What Comes Next

As spring arrives in Afghanistan, bringing with it the traditional fighting season that has shaped the country’s rhythms for decades, human rights monitors brace for what comes next. The code is now law. Its implementation will only deepen as Taliban institutions consolidate and judges grow more confident in applying its provisions.

For Afghan women, the trajectory is terrifying. Each new restriction, each codified inequality, each public punishment creates precedents that will be difficult to reverse even if the political situation changes. The code’s class provisions entrench hierarchies that will outlive any particular government, creating legal habits and expectations that shape how justice is understood for generations.

International options remain limited but not nonexistent. Some advocates argue for renewed focus on grassroots Afghan civil society, supporting the networks of women and human rights defenders who continue to document abuses and maintain alternative visions of Afghanistan‘s future. Others push for more aggressive diplomatic engagement, conditional aid, and pressure on neighboring countries that recognize the Taliban.

None of these approaches offers quick solutions. The code is here, and with it, a vision of Afghanistan that the international community has spent decades trying to prevent.

The Human Cost of Paper

In the end, what makes the code so devastating is its ordinariness. It is not a sudden explosion of violence but a systematic, bureaucratic inscription of inequality into the machinery of daily life. It makes discrimination routine, turns prejudice into procedure, transforms oppression from an act of individuals into a function of the state.

For the fruit seller in Mazar-i-Sharif, for the women in that Kabul apartment, for children across Afghanistan whose futures are being determined by judges who see them first through the lens of class and gender, the code is not an abstraction. It is the voice of the magistrate who asks about your family before your crime. It is the lash that falls differently depending on who you are. It is the law, written down and made real, telling you exactly where you belong.

And in a country that has known so much violence, so much upheaval, so much suffering, perhaps the cruelest thing about this new code is how familiar it feels—how naturally it extends patterns of inequality that have always existed, giving them the legitimacy of ink and paper, the permanence of statute, the authority of the state.

The gates of the appeals court remain open. Inside, justice continues its work, sorting Afghans into categories, assigning punishments according to status, and demonstrating, day after day, that some lives matter more than others under the law. The world watches, condemns, and moves on. Afghanistan lives with the consequences.

You must be logged in to post a comment.