Beyond the Headlines: The Constitutional Crossroads – 4 CJIs vs. 2, and What the Simultaneous Polls Debate Really Tells Us

Six former Chief Justices of India who testified before the Joint Parliamentary Committee reviewing the simultaneous elections Bill remain divided 4-2 on constitutional validity, with Justice B.R. Gavai joining Ranjan Gogoi, D.Y. Chandrachud, and J.S. Khehar in asserting that synchronising Lok Sabha and Assembly polls merely alters the procedural manner of voting without damaging federalism or the basic structure doctrine, while U.U. Lalit and Sanjiv Khanna have expressed reservations about potential violations of the Kesavananda Bharati framework—yet beneath this numerical split lies a more nuanced reality: all six expressed unease about unfettered powers the Bill grants the Election Commission, and the testimonies reveal not merely a legal disagreement but a deeper philosophical divergence between formalist justices who view the Constitution as a flexible rulebook accommodating parliamentary will and structuralists who read it as a delicate web of relationships requiring scrutiny of effects, not just text, underscoring that the simultaneous polls debate ultimately transcends constitutional permissibility to question whether electoral synchronisation serves Indian democracy at all.

Beyond the Headlines: The Constitutional Crossroads – 4 CJIs vs. 2, and What the Simultaneous Polls Debate Really Tells Us

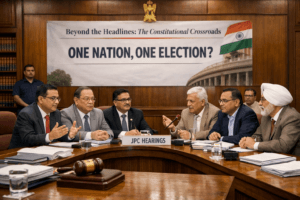

On a Thursday afternoon in February 2026, inside a wood-panelled committee room in Parliament, six men who once occupied the highest judicial office in the country sat—not together, but sequentially—to answer a single, sprawling question: Does holding all elections at once break the Constitution’s spine?

The setting was the Joint Parliamentary Committee reviewing the Constitution (129th Amendment) Bill, 2024. The verdict, if one can call it that, is now public. Four former Chief Justices of India—Ranjan Gogoi, D.Y. Chandrachud, J.S. Khehar, and the newest addition B.R. Gavai—have told the panel the Bill passes constitutional muster. Two others—U.U. Lalit and Sanjiv Khanna—have expressed serious doubts, arguing it may breach the basic structure doctrine.

But here’s what the 4:2 scoreline doesn’t capture. Behind each testimony lies not just a legal opinion, but a philosophy of how constitutions should breathe, evolve, and absorb change. This isn’t merely a debate about clubbing elections. It is a referendum on how India interprets its own foundational charter—and whether the “basic structure” is a fortress or a framework.

The Gavai Doctrine: Synchronisation as Procedure, Not Subversion

Justice B.R. Gavai’s deposition before the JPC on February 12 was characteristically precise. His core argument rests on a distinction that sounds simple but carries profound implications: the Bill, he asserted, alters only the manner of polling, not the structure of democracy.

Let us pause here. The phrase “only a change in the manner of elections once” is doing considerable legal work. It suggests that the Constitution, in Gavai’s reading, is indifferent to whether elections happen every five years in staggered cycles or every five years on a single Tuesday. What matters is that they happen—periodically, freely, fairly. The vessel changes; the wine remains the same.

This is a proceduralist view of constitutionalism. It holds that unless an amendment dismantles a core feature—federalism, secularism, judicial review, republican government—it remains within Parliament’s expansive amending power. Gavai reinforced this by pointing to the untouched architecture of accountability: no-confidence motions remain, opposition can still bring down governments, voters still choose their representatives.

To him, the Bill is constitutionally modest. It does not touch Articles 324 or 327 in a way that abrogates federalism. It merely permits the Election Commission to press a giant synchronise button.

The Dissenting View: When Procedure Becomes Substance

But two of his predecessors saw something else.

Justices U.U. Lalit and Sanjiv Khanna, both of whom served as CJI in recent years, reportedly told the committee that the Bill raises basic structure concerns. While their detailed testimonies remain confidential, the broad contour of their unease is not difficult to reconstruct.

The basic structure doctrine, born from the Kesavananda Bharati verdict of 1973, is India’s most original constitutional export. It says Parliament cannot destroy or damage the essential features of the Constitution even through a validly passed amendment. The question for Lalit and Khanna is whether forcing State Assemblies into the electoral cycle of the Lok Sabha—irrespective of their own tenure completion—damages federalism.

Federalism in India is not merely about demarcating subjects in the Seventh Schedule. It is about the political autonomy of States. A Chief Minister who knows her government’s life is tied to the Prime Minister’s political calendar does not govern the same way as one who commands an independent electoral mandate. The synchronisation mechanism, which may require shortening or extending the term of certain Assemblies to align with the national poll, arguably subordinates State political processes to Union political convenience.

This is not a procedural tweak. It is a recalibration of political power.

The Unspoken Consensus: Everyone is Uncomfortable with the Election Commission’s Powers

Here is a remarkable detail buried in the reporting: all six former CJIs, regardless of their bottom-line conclusion, expressed concerns about the unfettered power the Bill grants the Election Commission to decide election schedules, particularly for State Assemblies.

This is not a minor caveat. It is nearly a concurring dissent.

What unites the four and the two is a shared institutional anxiety. In the current scheme, the EC is a constitutional authority but its functioning depends heavily on executive acquiescence. The Bill, as drafted, proposes to empower the EC to notify the date of the first sitting of the House after a snap election, effectively determining when the five-year clock begins for the synchronised cycle.

Former CJI Ranjan Gogoi had earlier criticised this as excessive delegation. Chandrachud, during his tenure, repeatedly emphasised the need for institutional checks. Gavai himself, in his deposition, acknowledged that operationalising such a massive electoral exercise requires guardrails.

This is the paradox of the simultaneous elections project. To work, it requires immense faith in the Election Commission. But the same Constitution that created the EC also demands that no institution be left unaccountable. The former CJIs are signalling: trust, but verify. The Bill, in its current form, appears to skip the verification part.

What the Split Really Reveals About the Supreme Court Today

The 4:2 division among former CJIs is not merely a numerical coincidence. It reflects a deeper ideological chasm within the higher judiciary about the very purpose of constitutional adjudication.

One school—let us call it the “formalist” school—views the Constitution as a rulebook. If the rulebook permits an amendment to pass with two-thirds majorities, and the amendment does not explicitly repeal federalism or abolish elections, the court should defer. This is broadly the position associated with justices like Khehar and, to some extent, Gogoi.

The other school—the “structuralist” school—reads the Constitution as a web of relationships. Federalism is not just a word in Article 1; it is the lived reality of linguistic States, regional parties, and diverse mandates. Any amendment that distorts these relationships must be scrutinised for its effect, not just its text. This is the instinct behind Lalit and Khanna’s reservations.

Gavai’s position is interesting because it straddles both. He affirms parliamentary competence but insists on procedural regularity. He validates the goal but flags implementation risks. It is a judicial temperament that seeks to accommodate political projects without surrendering constitutional oversight.

The Politics of Constitutional Testimony

We must also acknowledge what is usually left unsaid. Former CJIs do not depose before parliamentary committees in a vacuum. They are invited because their opinions carry weight, but also because their presence lends legitimacy to one side of a polarised debate.

The timing of these depositions is not accidental. The Bill has been referred to a JPC amid Opposition protests that it is an assault on federal diversity. The government, through the committee chairman P.P. Chaudhary, has signalled its intent to push the Bill through. In this environment, a 4:2 scoreline in favour of constitutionality becomes a political asset.

Yet, no former CJI testified to please a party. These are men who have presided over the most contentious cases in Indian history. Their views are their own. But the fact that the committee chose to summon six former chief justices—and not, say, six constitutional law scholars or six former election commissioners—indicates the direction of the inquiry. The question is no longer whether simultaneous elections should happen. It is whether the Constitution can be shown to permit it.

The Missing Debate: Beyond Constitutionality to Desirability

Here is where the JPC’s approach reveals its limits.

All six former CJIs confined their testimony to constitutional validity. Not one, reportedly, was asked: Is this good for Indian democracy? That is not their remit, and rightly so. Judges interpret the Constitution; they do not design policy.

But the committee’s terms of reference blur this line. It is examining a constitutional amendment, so it must hear constitutional experts. Yet the Bill is not merely a legal instrument; it is a transformation of India’s electoral landscape. The wisdom of holding simultaneous elections—its impact on regional parties, on voter behaviour, on the rhythm of political accountability—is a distinct question from its constitutional permissibility.

By focusing overwhelmingly on the basic structure doctrine, the JPC is treating the Constitution as the only relevant battlefield. But a law can be constitutional and still unwise. It can pass the Kesavananda test and still fail the common sense test. The former CJIs have done their job. It is now for Parliament to do its own: to ask not just whether we can, but whether we should.

The Way Forward: What the 4:2 Split Does Not Settle

It is tempting to read the Gavai deposition as a turning point. Four former chief justices have blessed the Bill; only two have flagged concerns. The arithmetic favours the government.

But constitutional law does not work on a preponderance-of-views basis. The Supreme Court, if and when this Bill is challenged, will not count former CJIs. It will weigh arguments. The testimonies before the JPC are influential but not binding. They are data points, not precedents.

Moreover, the Bill still faces a parliamentary battle. The Rajya Sabha remains a hurdle. State legislatures, whose powers are directly affected, have not been consulted. The common electoral roll proposal, floated by Chairman Chaudhary as a logical extension, opens a separate front of controversy involving panchayats, municipalities, and the federal structure’s most granular tier.

The 4:2 split, therefore, is not a verdict. It is a snapshot of elite legal opinion in February 2026. It tells us that among the men who once wore the CJI gown, there is no unanimity. It tells us that the basic structure doctrine remains resilient enough to accommodate both defence and critique. It tells us that even those who support the Bill do so with conditions.

Conclusion: Reading the Constitution Forward

Every generation of judges reads the Constitution anew. The Kesavananda Bharati Bench read it as a document of restraints. Later Benches read it as an instrument of social transformation. The current generation, including those who have recently retired, is being asked to read it as a framework for governance reform.

Justice Gavai’s testimony is not remarkable because he sided with the government’s flagship legislation. It is remarkable because he articulated a coherent, defensible vision of constitutional change—one where Parliament leads, courts follow, and the basic structure stands guard only at the gates, not in every corridor.

The two dissenters are not obstructionists. They are sentinels. They see the same gates but worry the guards are asleep.

And the four who see no violation are not government apologists. They are interpreters who believe the Constitution can accommodate this experiment without breaking its own spine.

The Indian Constitution, as B.R. Ambedkar reminded the Constituent Assembly, is a workable document. It is not a prison. But neither is it a blank slate. The simultaneous elections debate is ultimately about where we draw the line between adaptability and abandonment. The former CJIs have drawn different lines. Now it is for Parliament, and eventually the people, to decide which line holds.

You must be logged in to post a comment.