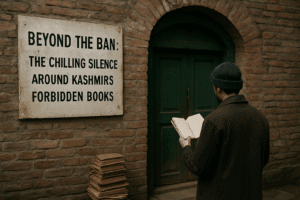

Beyond the Ban: The Chilling Silence Around Kashmir’s Forbidden Books

Anuradha Bhasin, whose own book on Kashmir is among 25 recently banned, dismantles the J&K administration’s justification that these works promote “sedition” and fuel terrorism. She highlights the complete absence of evidence linking the texts to violence and questions whether officials even read them, noting some are scarcely available foreign editions. Instead, Bhasin argues the ban is a blatant act of narrative control, coinciding with the Article 370 anniversary to reinforce state power and fear.

It continues a six-year pattern of silencing dissent by targeting journalists and archives under the guise of “normalcy.” The real damage, she warns, is the chilling effect on future scholarship and young Kashmiri minds deprived of diverse perspectives. While potentially sparking underground interest (a “Streisand effect”), the ban ultimately exposes government insecurity towards challenging truths. Bhasin concludes such censorship only strengthens her resolve to keep writing.

Beyond the Ban: The Chilling Silence Around Kashmir’s Forbidden Books

The recent banning of 25 books on Kashmir by the Jammu and Kashmir administration feels less like a reasoned security measure and more like a heavy-handed performance in silencing uncomfortable narratives. Author Anuradha Bhasin, whose own meticulously researched work “A Dismantled State: The Untold Story of Kashmir After 370” stands blacklisted, cuts through the official fog with a piercing question: Who actually read these books to uncover their alleged sedition?

The government notification paints a dramatic picture: these banned texts are accused of being “a significant driver behind youth participation in violence and terrorism,” peddling “false narratives,” “glorifying terrorism,” and “inciting violence.” It claims they cultivate “grievance, victimhood, and terrorist heroism.” Yet, as Bhasin sharply notes, this sweeping indictment comes utterly devoid of evidence.

The Unanswered Questions:

- Where’s the Proof? No interrogation records cite these books as radicalizing influences. No specific passages are quoted to demonstrate incitement. The link between these specific texts and violence remains a bureaucrat’s unsupported assertion.

- The Phantom Reader: Did some official, or committee, truly undertake the Herculean task of reading and analyzing these 25 diverse books – spanning history, politics, and personal accounts – to identify hidden “secessionist codes”? The lack of any substantive critique suggests otherwise.

- The Absurdity of Access: Bhasin points out the bitter irony: several banned books are expensive foreign editions, scarcely available in India. How could they realistically pose such an imminent, widespread threat?

The Likely Motive: Control, Not Security

Bhasin posits a more plausible, and disturbing, explanation: This is less about preventing violence and more about consolidating a singular, state-approved narrative of Kashmir. The timing is telling – coinciding with the sixth anniversary of the abrogation of Article 370, an event the government relentlessly frames as ushering in peace and progress.

“If all was well,” Bhasin asks pointedly, “why was there a need to go on a book banning spree?”

The ban appears as another tool in an established arsenal:

- Silencing Dissent: Following years of pressuring journalists, shuttering newspapers, and vanishing archives, book banning escalates the control over information.

- Reinforcing Fear: It sends a chilling message: Any narrative diverging from the official line is dangerous and punishable. It cultivates an “oppressive climate of fear.”

- Suppressing Scholarship: The long-term damage is profound. Young Kashmiri scholars lose access to crucial perspectives. Future researchers and writers will inevitably self-censor, fearing their work could land on a banned list. Publishers will grow hesitant.

The Irony and the Resilience:

The immediate effect might ironically mirror the “Streisand effect” – increased curiosity and underground demand for the banned books. However, the real cost is the erosion of intellectual freedom and historical understanding.

Bhasin’s response to the ban, and to those asking if she will stop writing, is unequivocal: “This article is my answer… for there is an even greater need to write now.” This defiance underscores the core issue – the ban isn’t about protecting security; it’s about controlling truth. When governments fear books, it reveals far more about their own insecurities and the fragility of their imposed “normalcy” than it does about the power of the written word to incite violence.

The Value of This Perspective:

Bhasin’s analysis moves beyond mere reporting. It offers:

- Human Insight: The personal stake of a banned author adds profound weight and authenticity.

- Critical Deconstruction: Systematically dismantling the government’s vague justifications exposes the lack of substance behind the draconian measure.

- Contextual Understanding: Placing the ban within the continuum of post-370 repression in Kashmir reveals it as a political tool, not a security necessity.

- Highlighting Consequences: Focusing on the chilling effect on future scholarship and free expression underscores the ban’s long-term cultural damage.

- A Stand for Principle: Emphasizing the increased need to write in the face of censorship is a powerful message of resilience.

The story of Kashmir’s banned books isn’t just about censorship; it’s a stark indicator of the space allowed for truth, dissent, and historical reckoning in the region today. The silence demanded by the ban speaks volumes about the narratives the authorities fear the most.

You must be logged in to post a comment.