Beyond the Ballot: Is the Election Commission’s Voter Revision Drive Becoming a Quiet Citizenship Test?

Activist Shiv Sundar has alleged that the Election Commission of India’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls is an unconstitutional, backdoor attempt to implement a National Register of Citizens (NRC), arguing that the ECI is illegally verifying citizenship—a judicial function—by demanding impractical documents like passports from poor, Dalit, and Muslim voters, using algorithmic suspicion of family structures to issue notices, and operating without legal mandate despite Supreme Court scrutiny; with 65 lakh names deleted in Bihar alone yet only two foreigners found, activists warn that this amounts to a mass disenfranchisement conspiracy targeting 25 crore citizens under the guise of electoral reform.

Beyond the Ballot: Is the Election Commission’s Voter Revision Drive Becoming a Quiet Citizenship Test?

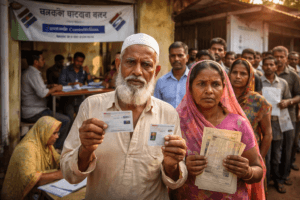

On a humid February evening in Vijayapura, activist Shiv Sundar stood before a room of writers, students, and Dalit rights workers and made an accusation that cuts to the heart of India’s democratic machinery. The Election Commission—that hallowed institution whose logo promises “Voter Turnout: The Heartbeat of Democracy”—was, he claimed, engaged in something far more consequential than fixing electoral rolls.

It was, he alleged, quietly preparing a National Register of Citizens by another name.

The workshop was ostensibly about electoral roll revision. But the anxiety in the room was palpable. Across Karnataka and several other states, ordinary voters—particularly the poor, the landless, and religious minorities—have been receiving notices that leave them bewildered and afraid. Produce your parents’ citizenship documents. Explain why your grandmother is 40 years older than you. Show us your government job certificate or your passport. These are not the usual queries about whether you still live at the same address.

Something has shifted in how India verifies who gets to vote—and by extension, who gets to belong.

The Quiet Expansion of Electoral Power

To understand what makes the Special Intensive Revision controversial, one must first understand what it claims to be. Electoral roll revision is routine. Names are added, removed due to death or migration, and clerical errors are corrected. The Election Commission has done this for decades without making headlines.

But the SIR, as it is currently being implemented, operates differently. Unlike routine revision, which is largely administrative, the SIR involves door-to-door verification, followed by hearings where voters must personally appear before electoral registration officers to defend their place on the roll. In states like Bihar, Assam, and now Karnataka, the numbers being removed are not trivial. In Bihar alone, 65 lakh names were purged from the voter list during SIR exercises. The number of foreigners actually found? Two.

This vast discrepancy between the scale of deletion and the scale of detected illegal immigrants is what troubles election watchdogs and civil liberties activists. When you remove 65 lakh people from the voter roll but can only identify two non-citizens, what exactly are you accomplishing?

The Election Commission’s defenders argue that many deletions are simply routine housekeeping—duplicate entries, deceased persons, people who have moved. But the activists at the Vijayapura workshop presented a different picture: one of poor, often Dalit or Muslim families receiving notices demanding citizenship proof based on what they called “flimsy grounds.”

A woman told to prove her mother’s citizenship because her mother gave birth at age 16—the age gap between them being less than 15 years, which the software flagged as suspicious. A landless labourer asked to produce a passport or central government employment certificate—documents his family has never possessed across three generations of Indian citizenship. A grandmother summoned to explain why her age and her grandchild’s age differ by only 40 years, as if multi-generational households and early marriage patterns in rural India were unknown to the algorithm.

These are not hypotheticals. They are happening now, in verification centres across the country.

The Supreme Court Admission That Changed Everything

For months, the Election Commission maintained that SIR was purely about electoral roll accuracy. The citizenship question, officials insisted, was not within their mandate. Citizenship is determined by the Foreigners Act and the Citizenship Act, adjudicated by special tribunals. The ECI’s job begins and ends with the voter roll.

Then came the admission before the Supreme Court.

According to activists and lawyers involved in ongoing litigation, the Election Commission’s counsel acknowledged that citizenship verification is indeed part of the SIR exercise. This was not a casual remark. It was a formal position stated before the country’s highest court, and it fundamentally altered the legal landscape.

If the ECI is verifying citizenship, it is doing something the Constitution and the Representation of the People Act do not explicitly authorize. More concerning, it is doing so through a process that lacks the procedural safeguards of citizenship tribunals. Those tribunals allow for legal representation, evidence submission, and appeal mechanisms. The SIR hearings are far more summary, often conducted by officials with no special training in citizenship law, and with far fewer opportunities for recourse.

“The Constitution is an obstacle,” Sundar told the audience in Vijayapura, “to the Fascist forces that are trying to turn the country into a Brahmin-Hindu corporatist state.” Whether one accepts his characterization of the government’s ideology or not, his underlying point deserves consideration: constitutional procedures exist precisely to prevent arbitrary determinations of something as fundamental as citizenship. When those procedures are circumvented through administrative mechanisms, the protection they offer evaporates.

The NRC Question That Won’t Disappear

The National Register of Citizens has had a strange political trajectory. First promised in the 2019 BJP manifesto, it was subsequently downplayed, then quietly shelved after the massive logistical failure and human suffering of the Assam exercise. In Assam, 19 lakh people were initially excluded from the final draft NRC. The process consumed years, cost crores, and left families in legal limbo. Many of those eventually cleared as Indian citizens spent months or years unable to access government services, travel, or even prove their identity.

When the all-India NRC was postponed indefinitely, many assumed the idea had been abandoned. But activists watching the SIR unfold saw familiar patterns. The same emphasis on documentary proof of lineage. The same suspicion falling disproportionately on Muslim and Bengali-speaking communities. The same administrative machinery being repurposed for citizenship verification under the guise of electoral revision.

The difference is scale and visibility. An explicit NRC would require new legislation, parliamentary debate, and a massive public information campaign. It would face Supreme Court scrutiny and likely provoke nationwide protests. The SIR, by contrast, operates quietly, district by district, hearing by hearing. It does not announce itself as a citizenship exercise. It arrives as a notice about your voter ID card, something most people do not think of as a citizenship document.

But citizenship and the franchise are deeply intertwined. Remove someone from the voter roll, and you have effectively rendered them stateless for electoral purposes. They cannot vote. They cannot participate in the democracy that supposedly governs them. And once their name is gone, restoring it requires navigating a bureaucracy that has already decided they do not belong.

The Document Trap

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the current SIR is the type of documentation being demanded. Election Commission guidelines specify that a range of documents can establish identity and residence for voter registration: ration cards, driving licences, bank passbooks, utility bills, Aadhaar, even SC/ST certificates. For the vast majority of Indians, these are the documents they possess and have always used to prove who they are.

But activists report that in many SIR hearings, these routine documents are being rejected. Instead, voters are being asked for passports or central government employment certificates—documents that, by definition, a large percentage of the population does not have and cannot easily obtain.

A passport requires proof of birth, proof of address, police verification, and fees that, while modest to the middle class, are significant for daily wage labourers. It also assumes a level of literacy and bureaucratic literacy that many rural poor do not possess. A central government employment certificate is even more restrictive—it applies only to the minority of Indians who work for the Union government, not state governments, and certainly not the vast informal sector.

This is what activists call the “document trap.” The state demands proof of citizenship, then rejects the proof that citizens actually possess, demanding instead documents that it knows they cannot produce. The outcome is predetermined. The hearing becomes not an inquiry but a formality, a box to check before exclusion.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that Aadhaar cannot be made mandatory for most services and that it is not proof of citizenship. Yet in some states, ECI officers are reportedly refusing to accept Aadhaar as valid documentation, despite these clear judicial pronouncements. This is not bureaucratic confusion. This is policy being implemented through administrative disobedience of judicial orders.

The Political Silence and Its Costs

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the current controversy is the political response—or lack thereof. In Karnataka, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah has publicly stated that the Congress party does not view SIR as a political issue. This is, as Sundar noted, “unfortunate.” When a state government declines to challenge what may be an unconstitutional expansion of electoral power, the institutional balance that protects federalism and civil liberties tilts dangerously.

One can understand the political calculus. SIR is framed as electoral integrity, and no party wants to be seen as defending “fake voters” or “illegal immigrants.” The BJP has successfully positioned itself as the party that takes election fraud seriously, and opposition parties, wary of being painted as soft on infiltrators, have largely avoided confronting the issue directly.

But this silence has consequences. When the political opposition abdicates its role, civil society becomes the last line of defence. Workshops like the one in Vijayapura, attended by writers and students and local activists, become the forums where constitutional questions are debated and citizens are informed of their rights. It is a fragile bulwark against what many see as a systematic administrative capture of democratic institutions.

The Algorithm of Suspicion

Underpinning the entire SIR controversy is a technological shift that has received far too little scrutiny. The Election Commission now uses software tools to identify “suspicious” entries in the electoral roll. These tools flag households where the age gap between mother and child is below a certain threshold, or where grandmother and grandchild are too close in age, or where a family has more than a certain number of children.

These are not neutral algorithms. They embed assumptions about what normal families look like that are deeply at odds with Indian social reality. Early marriage, particularly in rural and conservative communities, remains common despite legal prohibitions. Multi-generational households with small age gaps between generations are not unusual. Large families, while declining, still exist, particularly among poorer communities where child mortality remains a concern and where children are economic assets.

The software cannot distinguish between a family where a mother gave birth at 16 because of poverty and limited access to education and a family engaged in fraudulent registration. It simply flags both as anomalies, subjecting the former to the same scrutiny and documentary burdens as the latter.

The Supreme Court has already criticized the Election Commission for using “very restrictive” software tools “unable to fathom natural differences.” But the critique has not resulted in substantial changes. The algorithm continues to flag. The notices continue to issue. The poor continue to be summoned to prove that their families are real.

Citizenship as Battleground

What is unfolding through the SIR is not simply an administrative reform. It is a fundamental renegotiation of the relationship between the citizen and the state. Citizenship has traditionally been understood in India as a relatively stable status. Once acquired, it was not subject to periodic revalidation. You did not have to prove you were Indian every few years any more than you had to prove you were your parents’ child.

This is changing. The SIR represents a shift from citizenship as status to citizenship as performance—something you must continually demonstrate through the production of acceptable documents, the maintenance of properly spaced family relationships, and the avoidance of algorithmic suspicion.

For the urban middle class, this is an inconvenience at worst. We have passports and employment certificates and bank accounts. We can produce proof of our parents’ citizenship because our parents are government pensioners or taxpayers. The algorithms do not flag our families because our mothers did not give birth as teenagers and our grandmothers are appropriately distant in age.

But for the rural poor, for Dalits and Adivasis and Muslims, for migrant workers and informal labourers and women whose life trajectories did not conform to middle-class norms, this new regime is not inconvenience. It is existential threat. Their citizenship, which they have exercised through votes and ration cards and the simple fact of living their entire lives in Indian villages and towns, is now conditional. It depends on documents they do not have, on family structures they did not choose, on bureaucratic discretion they cannot predict or influence.

The Movement That Has Not Yet Begun

Sundar ended his Vijayapura address with a call for a mass movement, “on the model of the freedom movement,” to reverse what he described as a conspiracy against democracy. It is a stirring appeal, but one must ask: where will this movement come from?

The political parties are largely silent. The middle class is unaffected and therefore uninterested. The media covers SIR as a technical electoral story, not a civil liberties crisis. The affected communities are precisely those with the least political voice—the poor, the rural, the religious minorities, the socially marginalized.

And yet, if the activists are correct and the SIR is indeed a pilot for something larger—a nationwide citizenship verification exercise conducted through the electoral machinery—the numbers are staggering. An estimated 25 crore Indians could face citizenship scrutiny. Twenty-five crore people whose families have lived in this land for generations, whose ancestors fought for its freedom, whose labour built its economy, now required to prove that they belong.

That is not electoral revision. That is not administrative housekeeping. That is something else entirely.

What it is called matters less than what it does. And what it does is transform citizenship from a birthright into a privilege, from something inherited to something earned through the continuous, anxious production of acceptable paperwork. It makes every Indian potentially suspect, every voter potentially an illegal immigrant, every family tree potentially evidence of fraud.

The heartbeat of democracy, to return to the Election Commission’s own slogan, is not just voter turnout. It is the assurance that those who turn out to vote are recognized as full members of the political community. When that assurance is withdrawn—when millions are told that their names have been removed, their documents rejected, their citizenship doubted—the heart does not beat faster. It falters.

And a democracy that does not know who belongs to it will soon forget what it means to belong at all.

You must be logged in to post a comment.