Beyond Coal: How India’s Mining Giant Is Betting Big on Rare Earths to Break China’s Stranglehold

Beyond Coal: How India’s Mining Giant Is Betting Big on Rare Earths to Break China’s Stranglehold

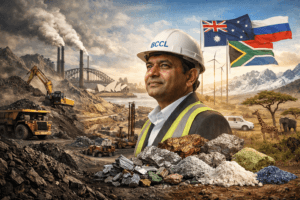

In a strategic pivot that signals a fundamental shift in global resource politics, India’s state-owned mining behemoth, Coal India, is setting its sights far beyond its traditional fossil fuel domain. Through its coking coal unit, Bharat Coking Coal Ltd (BCCL), the company is actively scouting for rare-earth mining partnerships across Australia, Russia, Argentina, Chile, and Africa. This move, confirmed by BCCL Chairman Manoj Kumar Agarwal, is not merely a corporate diversification tactic; it is a direct and calculated component of New Delhi’s national strategy to secure its industrial future by reducing a critical vulnerability: dependence on China-dominated supply chains.

The Geopolitical Catalyst: China’s Export Leverage

The impetus for this bold foray is unmistakably clear. In late 2025, China, which refines nearly 90% of the world’s rare earth elements (REEs), expanded its export controls on these critical minerals. This action sent shockwaves through global manufacturing, from automotive and defense to consumer electronics and renewable energy. Rare earths, a group of 17 metals with unique magnetic and phosphorescent properties, are the unsung heroes of modern technology. They are indispensable for manufacturing permanent magnets used in electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, smartphones, and advanced military hardware.

For India, a nation aggressively pushing its infrastructure and green energy ambitions, this dependency presents a strategic choke point. “In our country and in foreign countries also, we are going to invest; we are going to explore; we are also collaborating with other companies for rare earth metals. It is in the starting stage,” Agarwal stated. This “starting stage” represents one of India’s most significant raw material initiatives in decades, funded by BCCL’s recent blockbuster $119 million IPO, which was oversubscribed nearly 147 times.

A Two-Pronged Strategy: Global Scouting and Domestic Synergy

Coal India’s approach is deliberately two-pronged, targeting both international assets and domestic collaboration.

- The Global Chessboard:BCCL is looking at a diverse geopolitical portfolio.Australia offers political stability, established mining codes, and existing rare earth projects, making it a lower-risk partner. Russia possesses vast, untapped mineral wealth, and deeper mining ties could strengthen a strategic partnership already defined by energy trade. Meanwhile, Africa—particularly nations like Mozambique, Tanzania, and South Africa—holds rich deposits and represents a frontier where Indian investment can build long-term diplomatic and economic capital. Argentina and Chile, part of South America’s “Lithium Triangle,” are also in focus, suggesting India is thinking holistically about a basket of critical minerals beyond just REEs.

Simultaneously, BCCL plans to acquire coking coal mines in Australia and Russia within 2-3 years. This dual focus on securing both coking coal (for steel) and rare earths (for advanced tech) reveals a comprehensive vision: fortifying the entire industrial supply chain, from foundational materials to high-tech components.

- The Domestic Alliance:On home turf, Coal India intends to collaborate with key state-run players:

- IREL (India) Ltd: The country’s sole existing rare earths producer, with expertise in processing beach sand minerals.

- Khanij Bidesh India Ltd (KABIL): A joint venture specifically created to secure strategic mineral assets overseas.

- Hindustan Copper: Possesses mining and metallurgical expertise that could be leveraged for processing other hard-rock minerals.

This consortium model is intelligent. It pools expertise, shares financial risk, and avoids redundant efforts, creating a unified national front in the critical minerals race.

The Steel Ambition Underpinning the Move

This rare earth push should not distract from BCCL’s core mandate: fueling India’s steel revolution. The company aims to ramp up its coking coal production capacity from 40.5 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) in FY2025 to 56 MTPA by FY2030. This 38% targeted increase is a direct response to the government’s massive infrastructure push—building roads, railways, ports, and urban centers—all of which are steel-intensive.

Investors who flocked to BCCL’s IPO are betting on this very synergy. The capital raised funds both the expansion of the traditional coking coal business and the strategic diversification into rare earths. It’s a hedge: profits from securing essential steel ingredients today will fund the search for the materials needed for tomorrow’s high-tech economy.

The Human Insight: A Strategic Reawakening

Beyond the corporate announcements, this move marks a profound strategic reawakening for India. For years, the nation’s economic growth narrative has been challenged by its import dependency, particularly for energy and key minerals. Coal India’s evolution from a domestic coal producer to an international resource hunter represents a maturation of India’s state-owned enterprises. They are being tasked not just with domestic production, but with executing geopolitically sensitive resource diplomacy.

The challenges are formidable. Logistically, setting up new mining and complex processing chains from scratch is capital-intensive and technically demanding. Geopolitically, navigating partnerships in Russia amid sanctions, or in Africa amid competing Chinese and Western interests, requires deft statecraft. Environmentally, rare earth mining can be ecologically damaging, requiring stringent sustainable practices to avoid reputational risk.

However, the potential payoff is a more resilient, self-reliant Indian economy. Success would mean Indian manufacturers are not held hostage by foreign export controls, and that India can position itself as an alternative, democratic-node in the global critical minerals supply chain.

Conclusion: Building a Post-Coal Future

Coal India’s pivot is symbolic of a larger global trend: resource security is now at the heart of economic and national security. As the world decarbonizes, the competition is shifting from who controls the oil fields to who controls the lithium, cobalt, and rare earth deposits.

For Coal India, this is a forward-looking bet on its own relevance in a post-coal future. For India, it is a necessary step to ensure its “infrastructure decade” and “Make in India” ambitions are built on a foundation of secured resources. The journey from the coal fields of Jharkhand to the rare earth deposits of Australia and Africa is long and complex, but it is a journey that India can no longer afford to postpone. The race for the 21st century’s most critical elements is on, and a new player has decisively entered the arena.

You must be logged in to post a comment.