Beyond Bricks and Bytes: How India’s Judiciary is Building a Future of Empathetic and Equitable Justice

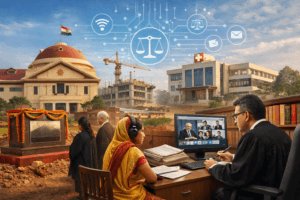

In a significant address at the Patna High Court, Chief Justice of India Surya Kant articulated a dual vision for modernizing India’s judiciary, framing technology as the essential catalyst for creating a transparent, accessible, and people-centric justice system, particularly for remote populations, while also championing substantial physical infrastructure investments—like new hospitals and staff quarters—that acknowledge the human element essential to judicial delivery. This integrated approach seeks to bridge the digital divide through digitized records and virtual access, thus empowering marginalized communities, while simultaneously ensuring the well-being of judges and staff who operate under immense pressure, thereby harmonizing digital efficiency with ancient Indian principles of open discourse and welfare embedded in sites like Nalanda to build a future where justice is both timely and empathetically rendered.

Beyond Bricks and Bytes: How India’s Judiciary is Building a Future of Empathetic and Equitable Justice

In the historic city of Patna, where the echoes of ancient Pataliputra’s administrative brilliance still resonate, a modern blueprint for justice is being drafted. It’s a blueprint that marries the enduring need for robust physical institutions with the transformative power of the digital age. Recently, Chief Justice of India (CJI) Surya Kant, while laying the foundation for new court infrastructure, delivered a powerful thesis: technology is not a mere adjunct to the justice system, but the very key to making it transparent, accessible, and truly people-centric. This moment in Patna is more than a ceremonial groundbreaking; it is a symbolic pivot point for Indian judiciary.

The Foundation: More Than Just Buildings

The seven projects initiated at the Patna High Court—spanning a new hospital, staff quarters, parking, and an auditorium—represent a critical, often overlooked, truth: justice is delivered by humans in human environments. CJI Surya Kant’s emphasis on a hospital building was particularly revealing. “Justice is delivered by humans, not machines,” he noted, highlighting the immense physical and mental strain on judges and staff. Chronic stress, backlogs, and the emotional weight of countless narratives of conflict take a toll. A healthcare facility within the court complex isn’t a luxury; it’s a foundational support system that acknowledges this human element, aiming to preserve the well-being of those who dispense justice.

Similarly, the proposed auditorium was envisioned as a “platform for judicial dialogue.” This speaks to the need for a living, breathing judiciary that evolves through discourse, continuing education, and intellectual exchange. Strong infrastructure, as Justice Rajesh Bindal termed these “temples of justice,” reduces logistical friction, allowing the focus to shift from managing chaos to deliberating on law and equity.

The Digital Bridge: Closing the Distance to Justice

While bricks and mortar provide the stage, technology is the script that can make the play of justice understandable and reachable for every citizen. CJI Surya Kant’s core message revolved around using technology as a great equalizer. The digitization of judicial records and processes is not about automation for efficiency’s sake alone; it’s about dismantling barriers.

For a daily wage worker in a remote village of Bihar or a tribal community in a forested region, the cost and ordeal of physically traveling to a court, often multiple times for procedural hearings, can make justice a theoretical concept rather than an accessible right. Virtual hearings, e-filing, and digital case tracking can collapse these geographical and economic distances. A farmer can attend a hearing via a video link at a designated Common Service Centre (CSC) in his block, saving crucial time and money. This is what making the judiciary “people-centric” genuinely means—designing it around the lived realities of its users, not the convenience of its administrators.

The launch of the Electronic Annual Confidential Report (e-ACR) at the Patna High Court, though an internal administrative tool, is a microcosm of this philosophy. By digitizing performance assessments, the system becomes more transparent, efficient, and less prone to delays or manual errors. It signals a judiciary that is willing to apply the principles of accountability and efficiency to itself first.

The Shadow of the Digital Divide and the Light of Legacy

However, CJI Surya Kant wisely coupled his tech-optimism with a note of caution: the imperative to bridge the digital divide. Technology, if deployed without mindful inclusion, risks creating a two-tier system—one for the digitally literate and connected, and another for the poor and marginalized. The true challenge lies in ensuring that digital courtrooms are complemented by physical facilitation centers, vernacular language interfaces, and robust digital literacy initiatives. Technology must be a bridge, not a new wall.

It is here that the CJI’s invocation of Bihar’s profound legacy becomes profoundly relevant. He recalled Nalanda not just as an architectural marvel, but as a global hub of “open debate, rational thinking, and knowledge exchange.” He remembered Pataliputra as a symbol of administrative excellence. This historical lens reframes the current efforts. The goal is not to create a cold, robotic legal system, but to use modern tools to resurrect those ancient Indian ideals: open access to knowledge (now through digital portals), rational discourse (facilitated by technology-aided research and dialogue), and welfare-oriented administration (through systems that serve the vulnerable).

The Patna High Court, thus, is being re-imagined as a modern-day Nalanda of justice—a centre where constitutional values are promoted not only through judgments but through the very architecture of its delivery.

The Human Imperative in a Digital Framework

The speeches that day struck a remarkable balance. Alongside the talk of servers and software was a resonant emphasis on empathy. “The true essence of justice lies in giving voice to the most vulnerable,” the CJI stated. Technology can streamline the process, but it cannot replace the judge’s discernment, the lawyer’s advocacy, or the system’s compassion. Justice Ahsanuddin Amanullah’s reminder that “justice should never be delayed” and infrastructure constraints are no excuse, was a call to use these new tools to fulfill an ancient mandate: timely justice.

The hospital and the high-speed broadband are two sides of the same coin. One tends to the human vessel of justice; the other clears the path for it to flow unimpeded. A judge in good health, supported by technology that eliminates clerical delays, is better positioned to listen patiently to that vulnerable voice and deliver a reasoned, timely verdict.

The Road Ahead: An Integrated Vision for 21st-Century Justice

The Rs. 320 crore infrastructure investment in Patna is a significant down payment on this future. But the larger investment is in mindset. The Indian judiciary’s journey towards a tech-enabled future must be guided by a few core principles:

- Inclusive Design: Every digital tool must be co-designed with end-users, including lawyers, litigants, and the smallest rural stakeholder, to ensure usability.

- Interoperability: Systems across different high courts and district courts must speak to each other. A truly national digital justice grid is the aim.

- Capacity Building: Continuous training for judges, staff, and lawyers on new technologies is as crucial as the technologies themselves.

- Preserving the Human Touch: Virtual hearings must not become impersonal. Procedures must safeguard the dignity and participatory rights of all parties.

In conclusion, the developments in Patna mark a holistic vision for judicial reform. It is a vision that understands that justice dwells in the intersection of human wisdom and technological aid, of grand infrastructures and granular digital access. By building both the physical and the digital simultaneously, and by anchoring it all in India’s timeless legacy of wisdom and welfare, the judiciary is attempting a monumental task: to ensure that the scales of justice are not only balanced but also within reach of every hand that seeks to place its evidence upon them. The foundation stone in Patna is, therefore, for a bridge—a bridge from the legacy of Pataliputra to the future of a truly democratic justice system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.