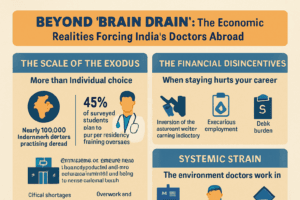

Beyond “Brain Drain”: The Economic Realities Forcing India’s Doctors Abroad

Indian doctors’ emigration is not merely a “brain drain” of individual choice but a systemic response to financial disincentives and professional hardships within the country’s healthcare system. Many face crippling education debts, stagnant or even reduced pay upon career advancement, and severe job insecurity due to contractual appointments and frequent salary delays, particularly in rural postings.

This occurs within an overstretched public system plagued by chronic underfunding, staff shortages, and often unsafe working conditions. While government initiatives like Ayushman Bharat aim to address gaps, the fundamental push factors—including better compensation, structured career paths, and respect abroad—continue to drive a significant exodus, underscoring that retaining talent requires systemic reform that makes serving in India a professionally viable and dignified choice.

Beyond “Brain Drain”: The Economic Realities Forcing India’s Doctors Abroad

In the heated debate about India’s “brain drain” of medical professionals, doctors are often framed as facing a simple moral choice: serve their country or seek personal fortune abroad. However, a closer look reveals a far more complex reality shaped by financial pressures, systemic deficiencies, and legitimate career concerns. This analysis moves beyond the binary debate to explore the economic and structural realities that drive thousands of India’s brightest medical minds to foreign shores each year.

The Scale of the Exodus: More Than Individual Choice

The migration of Indian doctors is not a trickle but a significant, documented flow. According to a 2025 OECD report, India is the single largest source of migrant doctors in OECD member countries, with nearly 100,000 Indian-born doctors practicing abroad. This trend is deeply rooted in the aspirations of medical students. A 2023 survey of over 1,199 Indian medical students found that 45% had concrete plans to pursue residency training overseas, with only 34% intending to stay in India.

The preferred destinations are telling: the United States (53%), the United Kingdom (32%), followed by Australia and Canada. This isn’t merely a quest for higher income; it represents a pursuit of structured career pathways, professional stability, and working conditions that many perceive as lacking at home.

Table: Key Drivers of Medical Student Emigration from India

| Driver | Percentage Citing as Factor (or Related Statistic) | Source |

| Plans to pursue residency abroad | 45% of surveyed students | |

| Better lifestyle & higher pay overseas | Most significant barrier to staying in India | |

| Top Destination: USA | Preferred by 52.6% of those going abroad | |

| India’s rank as source of migrant doctors in OECD | Largest source country |

The Financial Disincentives: When Staying Hurts Your Career

The economic argument against emigration often collapses under the weight of India’s own compensation structures. Doctors highlight a paradox where advancing in one’s academic career can lead to a pay cut.

- The Teaching Penalty: As reported in May 2025, a senior resident doctor in their final year at a Delhi hospital could earn approximately ₹1.6 lakh per month. Upon promotion to an Assistant Professor—a role that adds significant teaching and administrative duties—the salary falls to around ₹1.23 lakh. This inversion of the expected career-earning trajectory is a powerful demotivator for pursuing academic medicine in the public sector.

- Precarious Employment: The government’s increasing reliance on contractual appointments erodes job security. In Telangana, hundreds of contract professors and senior residents worked for nearly three months without salaries in 2025 due to administrative delays in extending their contracts. Similarly, bonded MBBS doctors serving compulsory rural postings in Uttar Pradesh’s Community Health Centres (CHCs) reported not being paid for over three months while earning a fraction of their urban counterparts’ salary. Such instability makes the predictable payrolls of foreign health systems deeply attractive.

- The Debt Burden: The cost of medical education in India creates immense pressure to earn. While top government colleges like AIIMS Delhi charge minimal fees (around ₹30,000 for an entire MBBS course), seats are fiercely competitive. Many students turn to private institutions, where total course fees can range from ₹70 lakh to over ₹1.2 crore. Graduates from these colleges often begin their careers burdened with substantial debt, making low or irregular government salaries a risky prospect.

Systemic Strain: The Environment Doctors Work In

The financial calculus occurs within a broader context of a strained public health system. India’s government spending on health, though increasing through initiatives like Ayushman Bharat, still hovers around 2% of GDP, significantly below the WHO‘s recommended 6%. This underfunding manifests in critical shortages.

A Right to Information (RTI) response from Delhi in 2025 revealed that 17% of medical officer posts and 38% of specialist posts in government hospitals were vacant. This understaffing increases the workload on existing doctors, contributing to burnout.

Furthermore, doctors in rural postings, who are crucial for extending healthcare access, often work with inadequate support and security. Those at UP’s CHCs reported a lack of safe accommodation, security personnel, and opportunities for professional growth. For women doctors, these safety concerns are particularly acute.

The Cuban Contrast: A Different Social Contract

The original article that sparked the reader comments contrasted India’s situation with Cuba’s system. Cuba’s approach is fundamentally different, built on a socialist political economy that emerged from its 1959 revolution. Medical education is free, and in return, doctors are salaried public servants. The system emphasizes preventive, community-based care, with doctors often living in the neighborhoods they serve.

This model has produced impressive health outcomes and a surplus of doctors, some of whom are deployed abroad on medical missions. However, it operates within a distinct social contract where individual financial reward is de-emphasized in favor of state-provided security and a collective ethos—a trade-off that exists in a very different political and economic context than India’s.

India’s Response and the Path Forward

The Indian government has launched significant initiatives to address healthcare gaps and retain talent. The Ayushman Bharat program aims to strengthen primary healthcare through Health and Wellness Centres and provide financial risk protection. The Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (PMSSY) works to correct regional imbalances by setting up new AIIMS and upgrading medical colleges.

Schemes under the National Health Mission (NHM) offer hard area allowances, honorariums for specialists in rural areas, and non-monetary incentives like preferential admission in postgraduate courses for service in difficult regions. However, as the cases of salary delays show, the effective, timely implementation of these policies remains a major challenge.

Addressing the exodus requires moving beyond blaming individual doctors and implementing systemic reforms:

- Ensuring timely and dignified compensation that rewards career progression.

- Formalizing recruitment and filling sanctioned posts to reduce reliance on insecure contractual positions.

- Investing in safe, supportive work environments, especially in rural areas, including security, housing, and professional development opportunities.

- Expanding postgraduate (PG) seats to reduce the intense competition that pushes graduates to seek training abroad.

The migration of Indian doctors is a symptom of deeper structural issues within the healthcare system. While their skills form the “backbone of global health systems”, the sustainability of India’s own health system depends on creating conditions where serving at home is a professionally and personally viable choice. The solution lies not in guilt, but in building a system that values and retains its healers.

You must be logged in to post a comment.