Batn al-Hawa Evictions: A Microcosm of Displacement and the Unfolding Battle for Jerusalem

The Palestinian neighborhood of Batn al-Hawa in East Jerusalem faces an unprecedented wave of evictions, potentially constituting the largest coordinated displacement there since 1967, as Israeli courts, leveraging a 1970 law that allows Jews but not Palestinians to reclaim historic properties, rule in favor of settler organizations like Ateret Cohanim which argues the land was originally owned by a Jewish trust.

Residents and rights groups contend that the war in Gaza has created a political atmosphere enabling this accelerated push, which aligns with the current right-wing Israeli government’s goals to consolidate a Jewish majority in Jerusalem; this legal campaign, framed as a property dispute, effectively advances settlement expansion, forcibly displacing hundreds of Palestinians like Zohair Rajabi and his family, erasing their multi-generational homes and deepening the reality of unequal rights in the occupied territories.

Batn al-Hawa Evictions: A Microcosm of Displacement and the Unfolding Battle for Jerusalem

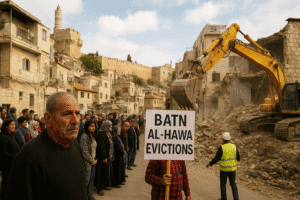

In the shadow of Jerusalem’s Old City walls, a quiet, determined battle over land, law, and legacy is reaching a climax. The Palestinian neighborhood of Batn al-Hawa, a tight-knit community of steep alleys and family homes, has become the epicenter of what may be the largest coordinated displacement of Palestinians from East Jerusalem since 1967. For residents like Zohair Rajabi, who has lived his entire 55 years in the same four-story house, the fight is nearly over. “Yes I have lost. I have been defeated,” he says, surveying the neighborhood where 34 families—approximately 175 people—now face “imminent displacement”. This is not an isolated property dispute but a pivotal front in a wider conflict, accelerated by the war in Gaza and driven by a discriminatory legal system that residents and rights groups argue is designed to ensure a Jewish majority in an eternally divided city.

The Legal Engine of Displacement

The mechanism driving the evictions is a 1970 Israeli law known as the Legal and Administrative Matters Law. This statute allows Jews to reclaim properties in East Jerusalem that were lost in the 1948 war. A parallel 1950 law, the Absentees’ Properties Law, explicitly prevents Palestinians from exercising the same right for properties they lost inside Israel during the same conflict.

In Batn al-Hawa, this law is being leveraged by the settler organization Ateret Cohanim. They argue that the neighborhood sits on land purchased in the late 19th century by a Jewish trust to house poor Yemeni Jews, who fled during the 1930s Arab revolts. Reactivating this trust, Ateret Cohanim’s lawyers have successfully petitioned Israeli courts to recognize its historic ownership, nullifying the purchases made by current Palestinian residents or their families decades ago. As of July 2024, the Jerusalem District Court has rejected appeals from four families comprising 66 people, ordering them to vacate their homes. Fourteen families have already been evicted.

Table: The Legal Status of Eviction Cases in Batn al-Hawa (As of July 2024)

| Status | Number of Families/People | Next Steps |

| Already Evicted | 14 families | Settlers have moved in. |

| Final Appeal Lost (Supreme Court) | 1 family (Shahadeh) | Forced eviction by police expected soon. |

| Appeals Pending in Supreme Court | 3 families (Odeh & Shweiki) | Awaiting state’s position. |

| Recently Lost District Court Appeal | 4 families (66 people) | Will request Supreme Court appeal. |

| Ongoing Lawsuits in Lower Court | At least 12 homes | Various early stages. |

The legal process presents a veneer of neutrality, but human rights organizations like Peace Now insist the matter is fundamentally political. They argue the government has multiple tools to halt the evictions, from expropriating the land for public use to simply instructing police not to enforce the orders on public safety grounds. However, with Israel’s most right-wing government in history, which includes ministers deeply committed to settlement expansion, such intervention is unlikely.

“An Atmosphere of Hate”: The Gaza War as Accelerant

Residents of Batn al-Hawa directly link the sudden urgency of their predicament to the war that began with the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023. “The war is a big factor,” says Rajabi. “If there was no war, maybe you would see one eviction every 10 years instead of five in 15 months. The war has created an atmosphere where you can push this through… An atmosphere of hate”.

This perceived “atmosphere” has two dimensions. First, the global focus on Gaza has, in the view of activists, provided cover for accelerated action in Jerusalem and the West Bank. Second, the war has intensified domestic Israeli politics, empowering hardline factions. Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who holds a ministerial role over civilian affairs in the West Bank, has openly declared his goal is to de facto annex the territory and prevent a Palestinian state. He has prioritized rapid settlement expansion, with 2025 already seeing a record number of new settlement housing units approved.

The linkage is not merely rhetorical. For many Palestinians, the assault on Gaza and the pressure in Jerusalem are parts of a single strategy. The Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, visible from Batn al-Hawa’s slopes, is a potent symbol of this connection. As the third holiest site in Islam and the most sacred in Judaism (known as the Temple Mount), control over it is intensely contested. Incursions or tensions at Al-Aqsa have repeatedly ignited wider violence, including the Second Intifada. Its proximity makes Batn al-Hawa not just a residential area but a strategic foothold in the battle for the Old City’s periphery.

A Pattern of Expansion: From Jerusalem to the West Bank

The campaign in Batn al-Hawa mirrors a dramatic surge in settler violence and land appropriation across the occupied West Bank. According to the UN, October 2025 saw the highest number of violent settler attacks recorded in nearly two decades—an average of eight incidents per day. These attacks, particularly intense during the olive harvest, have injured hundreds of Palestinians and destroyed thousands of trees.

The violence is often systematic and goes unpunished. Yesh Din, an Israeli rights group, found that over 93% of police investigations into settler attacks against Palestinians between 2005-2024 were closed without indictment. In one stark incident in November 2025, masked settlers beat and robbed Italian and Canadian volunteers who were accompanying Palestinian villagers in the West Bank, shouting that they had “no right to be there”.

This environment of impunity, coupled with high-level political support, creates what Palestinian authorities call a campaign of “intimidation and terror” designed to make life untenable and force people off their land. The goal, as stated by settler leaders, is the completion of the “Zionist dream”—the consolidation of Jewish control from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River.

Silenced Stories and Global Complicity

The battle for Batn al-Hawa is also a battle over narrative. A 2024 UN report warned that the Gaza war has triggered an unprecedented global assault on freedom of expression regarding Palestine. The report details the killing and detention of journalists, the banning of protests and Palestinian symbols in Western countries, and the silencing of scholars and artists. This creates a paradox: while social media allows raw, firsthand accounts from Gaza to circulate, structured journalism that provides context and investigates power is under severe pressure.

This silencing extends to the legal sphere. In Batn al-Hawa cases, Israeli experts in international law submitted a brief to the Supreme Court arguing that under human rights law, the Palestinians’ right to housing and established home life should trump historic ownership claims, especially given their status as a vulnerable group under occupation. The court read the brief but did not reference it in its decision, continuing to frame the issue as a private real estate dispute.

Conclusion: The Weight of a Stone

For the international community, the evictions in Batn al-Hawa present a critical test. They are a clear example of the “daily reality” of occupation that persists alongside headline-grabbing wars. As Dahreen Rajabi, 15, contemplates leaving, she says, “Every stone here is a memory for me”. Her statement captures the profound human cost—the erasure of personal history, community, and a sense of belonging.

The outcome in this one neighborhood will signal whether the principle of “facts on the ground”—the alteration of demography and geography through force and law—will continue unchallenged. If the evictions proceed, they will not only displace hundreds but will further entrench a one-state reality of unequal rights, moving the region farther from peace and closer to a future of perpetual conflict. The stones of Batn al-Hawa, laden with memory for its children, are also the building blocks of a grim new political architecture for Jerusalem and beyond.

You must be logged in to post a comment.