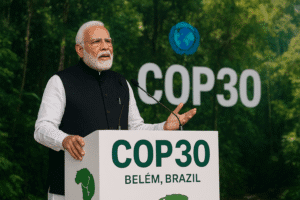

At COP30, India Draws a Line in the Amazon: Equity, Finance, and the Unfinished Business of the Paris Agreement

At the COP30 climate summit in Belém, India, speaking on behalf of the BASIC and Like-Minded Developing Countries groups, delivered a forceful argument that the foundational principles of equity and climate justice must guide all negotiations. Reaffirming the non-negotiable principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR-RC), India identified fulfilled climate finance from developed nations as the critical barrier to greater ambition, demanding a universally agreed definition and a massive scale-up of adaptation funding.

The nation framed technology access as a right, not a bargaining chip, warned that unilateral trade measures like carbon borders undermine multilateral cooperation, and argued that a “just transition” must be global and people-centric, aimed at narrowing the North-South development gap rather than protecting it. Ultimately, India’s statement served as a defensive of the Paris Agreement’s original structure, insisting that developed countries must lead by fulfilling their legal obligations on finance and technology to preserve trust and enable collective, ambitious action.

At COP30, India Draws a Line in the Amazon: Equity, Finance, and the Unfinished Business of the Paris Agreement

BELÉM, Brazil – A decade after the historic Paris Agreement was forged in a spirit of collective ambition, the global climate conversation has reached a critical inflection point. As delegates gathered in the lush, biodiverse heart of the Amazon for the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP30), the air was thick not just with humidity, but with a palpable sense of urgency and unresolved grievances. In this charged atmosphere, India, speaking as the voice for nearly half of the world’s population, delivered a powerful and unambiguous message: the path to a livable planet must be paved with equity, climate justice, and a return to genuine multilateralism.

Representing both the BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China) coalition and the larger Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) group, India’s opening plenary statement was more than a diplomatic formality; it was a strategic framing of the core battles that will define the success or failure of this pivotal summit. It marked a clear stance that while the destination—a net-zero world—is shared, the journey must account for who has driven the climate crisis and who is left most vulnerable by its effects.

The Unshakeable Pillars: Equity and CBDR-RC

At the core of India’s argument lies the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC). To the uninitiated, this may sound like bureaucratic jargon, but it is the bedrock of climate justice. It is the acknowledgment that while all nations must act, the scale and pace of that action cannot be the same for an industrial power that built its wealth on two centuries of fossil fuels as it is for a nation still lifting millions from poverty.

India’s reaffirmation of this principle is a direct response to a growing trend in global climate politics: the subtle erosion of this differentiation. Developed nations, India and its allies argue, are increasingly pushing for a regime where emerging economies take on near-identical burdens, effectively rewriting the foundational compromise of the Paris Agreement. By stating that “the architecture of the Paris Agreement must not be altered,” India is issuing a defensive warning against any attempts to shift the goalposts and blur the lines of historical responsibility.

The Critical Enabler: Demystifying and Delivering Climate Finance

If there is one issue that India has pinpointed as the “key barrier to raised ambition,” it is climate finance. A decade after the Paris promise, the discourse remains mired in a fundamental disagreement over what even constitutes ‘climate finance’. Developed nations often count loans, private investments, and re-labeled development aid in their figures, creating a picture of generosity that is at odds with the reality experienced by developing countries.

India’s call for a “clear and universally agreed definition” is therefore not a minor technicality; it is a prerequisite for trust and accountability. Without it, the $100 billion-a-year promise—itself a figure acknowledged as inadequate and still not fully met—becomes a moving target, impossible to pin down or verify.

Furthermore, India highlighted the stark disparity in adaptation financing. The statement noted that current flows need to increase by nearly fifteen times to meet the needs of vulnerable communities. This is not an abstract number. It translates to seawalls for sinking Pacific islands, drought-resistant seeds for sub-Saharan farmers, and early-warning systems for Himalayan communities facing glacial lake outburst floods. For the billions living on the frontlines of a crisis they did not create, adaptation is not a future plan; it is a daily struggle for survival. By demanding that COP30 be “the COP of Adaptation,” India is forcing the world to look beyond mitigation graphs and into the eyes of those for whom climate change is an immediate existential threat.

Technology as a Right, Not a Privilege

In the race to decarbonize, technology is the great differentiator. The nations that control the patents for solar panels, green hydrogen, and advanced battery storage hold the keys to the clean energy kingdom. India’s statement directly challenges this potential technocracy, asserting that “Technology Access is a Right, not a Bargaining Tool.”

This position strikes at the heart of a major tension in the climate talks. Intellectual Property (IP) rights, fiercely protected by corporations and developed nations, often render critical green technologies prohibitively expensive for the Global South. India argues that this creates a “climate tech apartheid,” where the tools for a sustainable future are available only to those who can afford them, locking in a new form of dependency and inequality.

A “strong outcome on the Technology Implementation Programme” would, in India’s view, involve mechanisms to overcome these IP and market barriers—through voluntary licensing pools, public-funded buy-downs of patents, or massive scaling-up of collaborative R&D. The alternative is a world where the energy transition widens the development gap instead of closing it.

The People-Centric Transition: Justice Beyond Borders

The concept of a “Just Transition” has gained global currency, but its interpretation varies widely. In the Global North, it often focuses on protecting workers in sunset industries like coal. India, representing the LMDC, expands this vision into a broader, more profound framework. For them, the UNFCCC Just Transitions Work Programme must ensure that the entire global economic shift is “rooted in equity and justice.”

This means that the transition cannot simply be about replacing fossil fuels with renewables within national borders. It must be about “narrowing the development gap between the Global North and South.” A just transition, in this view, requires that the economic opportunities of the green revolution—the manufacturing, the jobs, the technological learning—are shared globally. It is a rejection of a future where the South remains a mere consumer of green technology produced in the North, thereby perpetuating historical patterns of economic disparity.

The Specter of Unilateralism: A Threat to Multilateral Cooperation

One of the most pointed critiques in India’s statement was its caution against “unilateral climate-related trade measures.” This is a direct reference to policies like the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which aims to tax carbon-intensive imports.

While framed as a climate measure, India and many developing nations see such policies as a new form of “green protectionism.” They argue that these measures unfairly penalize their industries, which are often less carbon-intensive in their production methods than the historical industries of the West. More dangerously, they undermine the spirit of the UNFCCC, which calls for cooperation and rejects measures that constitute “a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade.” By raising this issue, India is defending the principle that climate action should be negotiated collectively, not imposed unilaterally through economic coercion.

A Call for Leadership and Legacy

By speaking for both the BASIC and LMDC blocs, India is positioning itself as a central, pragmatic, and principled broker in the complex geopolitics of climate change. Its statement is a powerful reminder that the success of COP30 will not be measured by lofty rhetoric alone, but by tangible progress on the foundational promises of finance, technology transfer, and adaptation support.

The message from Belém is clear: the trust deficit between the Global North and South remains the single greatest obstacle to climate progress. India has laid down a marker, asserting that the way to rebuild that trust is not by renegotiating the principles of equity, but by finally, and fully, honoring the commitments made under them. As the world watches the negotiations unfold in the Amazon, the question is whether developed nations will respond with the necessary scale of action, or if the promise of Paris will continue to be eroded by delay and unfulfilled promises. The fate of our shared planet hinges on the answer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.