A Noose for Some: Israel’s Divisive Death Penalty Push Exposes a Justice System at a Crossroads

Israel’s Knesset, propelled by far-right National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir and his Otzma Yehudit party, has advanced a contentious bill to reintroduce the death penalty specifically and exclusively for Palestinians convicted of killing Jewish Israelis, while explicitly exempting Jewish perpetrators—a distinction critics condemn as a “deeply racist” foundation for a two-tiered justice system.

Promoted as a necessary deterrent against terrorism and a means to prevent future prisoner swaps, the mandatory penalty has garnered support amid heightened conflict, despite data showing widespread violence against Palestinians with near-total impunity for Israeli settlers. Human rights organizations warn the law could enable mass executions of the roughly 9,000 Palestinian security prisoners already detained and risks further isolating Israel internationally by blatantly violating principles of equality before the law, marking a profound ethical crossroads for the nation’s democracy and its standing in the global community.

A Noose for Some: Israel’s Divisive Death Penalty Push Exposes a Justice System at a Crossroads

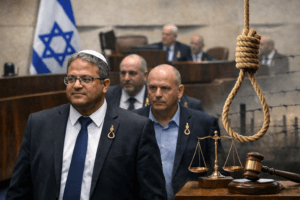

The image was jarring, even amidst the unrelenting torrent of conflict imagery: Israeli lawmakers, led by National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, filing into the Knesset wearing sleek, golden lapel pins shaped like hangman’s nooses. This macabre fashion statement wasn’t for a historical drama; it was for a first reading of legislation aimed at reintroducing the death penalty in Israel. But the proposed law, which passed that initial hurdle, contains a staggering caveat: it would apply only to Palestinians convicted of killing Jews, not to Jews who kill Palestinians. This isn’t merely a tough-on-crime policy; it is a legislative proposal that codifies a two-tiered justice system, laying bare profound ethical fractures within Israeli society and threatening to ignite further international condemnation.

Beyond Deterrence: A Law Built on a “Deeply Racist” Premise

Proponents, primarily from Ben-Gvir’s far-right Otzma Yehudit party, frame the bill as the ultimate deterrent. “Terrorists deserve death,” Ben-Gvir declared. Limor Son Har-Melech of the same party stated bluntly, “There is no such thing as a Jewish terrorist.” The legislation targets those whose murders are motivated by hatred “towards the public” and intended to harm “the State of Israel and the rebirth of the Jewish nation.” It would be mandatory, stripping judges of sentencing discretion, and would apply across all territories under Israeli control—Israel proper, the occupied West Bank, and currently, much of Gaza.

However, human rights organizations and civil liberties advocates have eviscerated the proposal. Noa Sattath, executive director of the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, calls it “a celebration of death and revenge and brutality.” The central criticism is its explicit discrimination. By legally distinguishing between victims based on nationality and ethnicity, the law institutionalizes inequality before the law—a cornerstone of democratic justice. Critics fear it could also be applied retroactively to the approximately 9,000 Palestinian security prisoners already in Israeli jails, including hundreds detained after the October 7 attacks, potentially enabling what Sattath describes as “mass executions.”

The Personal and The Political: Grief Weaponized

The political drive for this law is deeply intertwined with personal tragedy and the fraught mechanics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Pro-advocacy group “Choosing Life” frames its support as a matter of security. Member Dan Lando, whose son-in-law was stabbed to death by a Palestinian assailant in 2017, argues the death penalty would stop attackers from receiving “nice payments from the Palestinian Authority.”

He references the longstanding Palestinian Authority (PA) practice of providing stipends to families of prisoners and those killed, which Israel condemns as incentivizing terrorism, while Palestinians view it as essential support for families devastated by occupation and incarceration. (The PA has recently announced abolishing these payments, a move tied to political pressure.) For Lando, the law is logical: “If they go out with a knife or with a gun and intend to kill somebody… they will get sentenced to death.”

Yet, when confronted with the bill’s discriminatory nature, Lando’s justification falters. He claims, “There is no pandemic of Jews killing Palestinians,” and that Israel jails Jewish perpetrators. Data and human rights reports comprehensively contradict this. In the West Bank, settler violence against Palestinians has reached unprecedented levels, often with impunity. Israeli human rights group B’Tselem asserts that the state “effectively condones and encourages” such violence by rarely convicting settlers. Since October 7, the Hamas-run health ministry in Gaza reports over 70,000 killed by Israeli military action, a campaign the UN has said amounts to prima facie genocide. The proposed law’s exclusive focus ignores this overwhelming asymmetry in lethality and accountability.

A Chilling Historical Echo and a Diplomatic Minefield

Israel has carried out the death penalty only once in its history: in 1962, against Nazi architect Adolf Eichmann. That execution was a singular, watershed moment of justice for crimes against humanity. Equating the proposed judicial killings—which could be carried out by lethal injection, according to some reports—to the Eichmann case is a narrative that supporters might crave, but it is a false equivalence. This would not be a rare judgment for historic, industrialized genocide, but a systematized punishment in an ongoing, asymmetric national conflict.

The potential diplomatic fallout is severe. As former Palestinian Authority minister Qaddura Fares notes, some in Netanyahu’s coalition may block the bill not out of moral concern, but to avoid further isolating Israel on the world stage. Passing a law that so blatantly violates international human rights norms on equality and the right to life could fracture relations with even staunch allies and provide potent ammunition for proceedings at international courts.

For Palestinians, the law is seen as an extension of existing realities. “We are killed everywhere, every day, without any reason,” says Fares. He views it cynically, as merely changing the method: “instead of being killed by shooting or by a settler … it will come from the courts.” It reinforces a pervasive sentiment that Palestinian life is valued less under a system where, as rights groups note, hundreds of Palestinians can be held as “administrative detainees” without charge—a tool almost never used against Jews.

Conclusion: A Threshold Moment for Israeli Democracy

The “noose bill” is more than a piece of proposed legislation; it is a stress test for Israeli democracy and a mirror to its current political ethos. It reduces complex, grievous human suffering to a brutally simplistic and discriminatory formula. It exploits genuine security fears and personal grief to advance a vision of justice that is blatantly partial.

The path forward is fraught. As the bill is reworked in committee, the world watches to see if Israel’s legislature will cross a line that it has approached only once before in its history, and for profoundly different reasons. Whether this bill becomes law or not, its very proposal marks a dangerous normalization of extremist rhetoric and a potential point of no return for a justice system struggling to uphold its integrity amidst relentless conflict. The golden noose, in the end, may be a symbol not just for those it would execute, but for the ideals of equal justice it seeks to strangle.

You must be logged in to post a comment.